I’m looking forward to seeing the big Gwen John exhibition at National Museum Wales in Cardiff. Few people now ask ‘Who is Gwen John?’, though it’s taken more than half a century for the world to catch up with Augustus John’s reported assessment of her work after she died in 1939: ‘in fifty years’ time I will be known as the brother of Gwen John’.

In the meantime I’ve been preparing by taking a closer look at three of Gwen John’s painted self-portraits. She seems to have made only three complete paintings of herself. All of them date from the earliest years of her life as a painter, not very long after she had left the Slade School of Art. Together they say a great deal about how she saw herself and how she chose to present herself to her teachers and her peers.

The Slade School was an unusual institution. Founded in 1871, it was the only major art school that had admitted women from the start, and by the time Gwen followed her brother there in 1895 women student outnumbered the men. They were still educated separately, but outside the classroom social interactions were much more fluid than those in Gwen’s home towns of Haverfordwest and Tenby, and she developed many relationships among the students. Some of these friendships lasted for years. ‘Gwen John the recluse’ was always a myth, but certainly at this stage she was as sociable as any art student.

Gwen left the Slade in 1898, laden with prizes, and moved to Paris to be taught by James McNeill Whistler. Not long afterwards she painted the first of the three self-portraits, in 1899 or 1900. It seems to have been included in a show in the New English Art Club in London in spring 1900 (possibly Gwen’s first public exhibition), where it’s listed as Portrait of the artist (it’s now known simply as Self-portrait and sits in the National Portrait Gallery).

It’s a striking, or even daunting, picture. To begin with, it’s large in size, 61 x 37.8cm. Since the background and Gwen’s dress are both in subdued colours (dark brown and reddish-brown), you’re immediately drawn to the brighter face. It bears a cool, proud or even stern look. The eyes are fixed and unlikely to blink soon, the lips are narrow and drawn firmly shut. Her hair is plain and scaped back behind the ears. That might suggest a reserved or even puritan character. But the rest of the picture seems to contradict that impression. The dress is full and characteristic of late-Victorian women’s clothing, with multiple folds, especially in the sleeve, that are as busy as the face is placid. Two other elements add to the extravert, assertive note: Gwen’s right hand rests firmly on her waist, and her (exceptionally long) neck is covered with an exuberant black bow.

How could you sum up the sort of woman – she was still around twenty-four years old, but not in any sense a girl – who’s being introduced to us here? Calm and confident, maybe, self-contained but easy enough in company, assertive and capable of claiming her rightful place in the world. Assertiveness was an easily understandable position. When it came to exhibitions, women artists found it very hard to break male domination: in the 1900 NEAC exhibition only sixteen women, including Gwen, were represented, compared with seventy-five men.

The second painting, Self-portrait in a red blouse, now in the Tate, couldn’t be more different. It dates to a slightly later period, between 1900 and 1902. Everything here is reduced and pared down, in comparison with the first self-portrait. The canvas is rather smaller (44.8 x 34.9cm). Again the background is a uniform brown, but of a lighter tone. In the earlier painting the face is at the top of the canvas, giving an impression that we’re looking up at it, but here the figure is lower, and smaller in the frame.

The most striking difference lies in the dress colour – a bright red, with parallel black lines. That might suggest an even more assertive impression, but actually the reverse is true. For all its colour, the dress is inexpressive. Gwen no longer feels the need to ‘make a stand’. There’s no defiant hand on hip. The ebullient bow has been replaced by a modest ribbon, fronted by a cameo brooch. The face stares at us with the same impassivity, but somehow it lacks the pride of the first portrait.

This seems a subtler painting. Though at first sight the composition is plain and boldly frontal, the lighting gives it life, and almost everything in it is off-centre and asymmetrical. The face is turned ever so slightly to the left, and slightly cast down, and the eyeballs are not completely aligned. The shoulders don’t quite match each other. The dark shawl or wrap that has dropped from the right shoulder anchors the figure.

Self-portrait in a red blouse is very different in feeling from the earlier portrait. This isn’t a woman who’s just burst into the room to make a statement, she’s been standing here quietly watching us for some time. But it carries the same message, one of calm self-confidence and certainty of artistic direction.

The painting was noticed straight away. It was shown in an exhibition at the Slade in 1902, and Augustus hailed it as ‘a wonderful masterpiece’. Frederick Brown, Gwen’s old teacher in the Slade, bought it for his own collection (it appears on the wall in his own self-portrait of 1926). Her former lover, Ambrose McEvoy, painted a portrait of her wearing the same cameo.

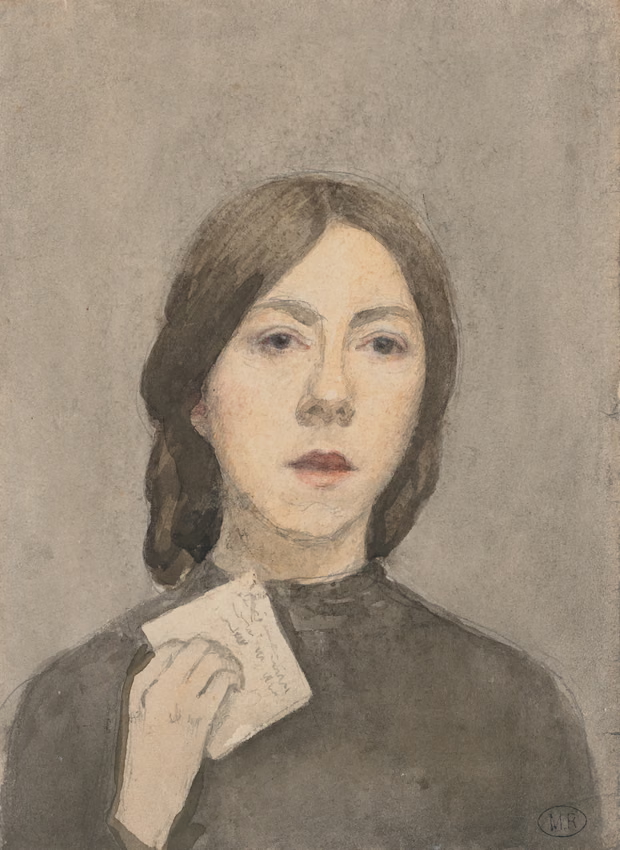

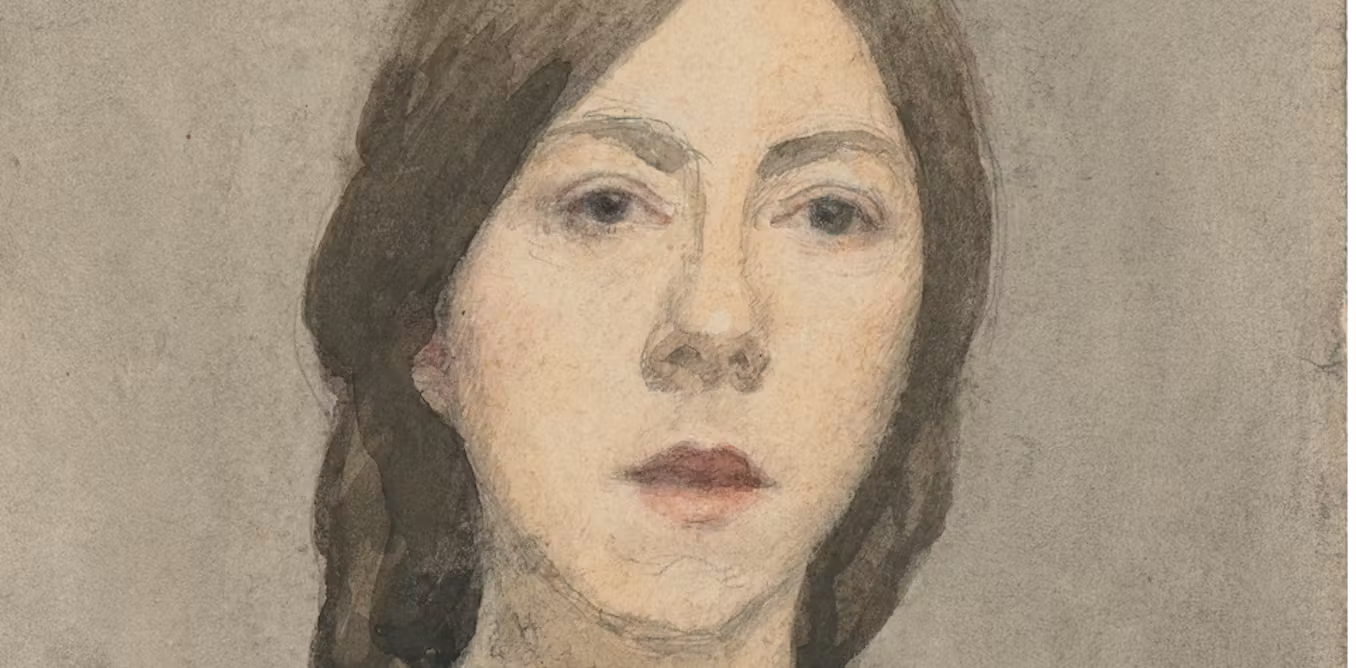

Five years and more passed before the third portrait, entitled Autoportrait à la lettre, dated to c.1907-9. By now she’d walked across France with Dorelia McNeill, settled in Paris, and become a model and lover of the sculptor Auguste Rodin. The relationship with Rodin was lengthy and sensual, and loosened Gwen’s remaining inhibitions. She wrote for him a series of imaginary letters, from ‘Marie’ to ‘Julie’, which explored sexual pleasure in frank detail. She made several sketches of her naked body, evidently for Rodin’s eyes. These were not seen in public, though Gwen did exhibit in 1910 a near-nude (and distinctly unsensual) oil painting of Fenella Lovell.

Autoportrait à la letter shares some features with Self-portrait in a red blouse. The head is again placed low on the canvas. There’s the same direct, unblinking gaze, and the same slight asymmetries in the slant of head and shoulders. But the ‘paring down’ has gone much further. There’s no bright red, except for the lips, and all the other tones, including the plain background, are muted to shades of grey and brown. Instead of a dress, Gwen wears a plain smock. In part the painting owes its paleness to the fact that Gwen has here abandoned oil paint for pencil and watercolour. This frees her from any obligation to render surface detail or temptation to use brighter colour.

Her right hand makes a reappearance from the first self-portrait, though this time it doesn’t serve to signify self-confidence. It holds up a letter. For centuries artists had painted women holding or reading letters, a shorthand to indicate the emotional engagement of the subject with the letter’s writer. The viewer has no way of reading the letter, or of interpreting the woman’s reaction to reading it without resorting to conjecture. What makes Autoportrait à la letter so distinctive and mysterious is the lack of emotional reflection of the letter’s message in the face of its recipient.

Gwen seems to have made the picture as a gift to Rodin. In an undated letter to him she wrote to say that she’d made several drawings of herself in a mirror for him, though she found it ‘difficult to draw’.

The relationship with Rodin was over by 1913 and Gwen became more and more attached to her Catholic faith. There were no more self-portraits, so far as I can see. The outward aspect of the self no longer felt important, and her thoughts about herself now revolved around her interior life (though she kept a keen interest in other people, animals and objects). Perhaps the nearest of her later paintings to self-portraits are the two small oil paintings entitled A corner of the artist’s room, which feature an open window, a wicker chair and a table. The artist, though implied by her few possessions, is invisible. There really isn’t any need, it seems, for more self-statements, however undemonstrative.

Leave a Reply