1

When I arrive, the ward is full. I’m redirected to where the ophthalmology patients wait. It’s a poor fit: my body part for attention is some way south of the eyes. The surgeon comes, to tell me briefly what could go wrong. A nurse tells me to undress, and leaves two items of hospital clothing. I put the gown on the wrong way round and mistake the gauze pants for a bonnet. (To be fair, it did cross my mind that it was strange an almost hairless person would need a hat.) I tell the nurse she’s free to amuse her colleagues with this example of witless innocence – as long as she stresses that my hospital experience is very limited.

2

You get used to being asked the same questions about your body and your medications several times over – I assume, in the interests of safety, for both patient and hospital. It’s a bit unsettling, though: repeated questioning is a well-known technique used in hostile interrogation, and, according to my daughter, in the newer, sinister kinds of AI-driven personality test used in staff recruitment.

3

Preparing for theatre. Small talk is an acknowledged technique for calming the patient. It’s easy if you’re from Swansea. It turns out that the anaesthetist’s brother went to Swansea University – and had a good time there – and a nurse’s brother plays for Swansea City. With more time we might have found other local connections. But the anaesthetist’s potion is already speeding up the canula, and a mask descends on my face. Within a second I’m climbing steeply, into the deep blue depths of the upper atmosphere.

4

The recovery room feels weirdly icy. Someone in a surgical hat passes by and gives me a thumbs up. Or maybe I’m hallucinating. I’m trolleyed to the ward (Bed 1, Room 6), which feels, at the time, deliciously warm. Though in fact it’s almost unbearably hot. Today is the peak of the heatwave.

5

The neurologist Henry Marsh, now himself a patient, wrote recently that hospitals are like prisons. You’re stripped of your own clothes, acquire a number, receive large numbers of instructions and plastic bracelets, and lose all sense of personal agency. (Back in 1961, in his book Asylums, Erving Goffman had the same thought and gave hospitals the hostile label of ‘total institution’.)

But there’s a quite different way of looking at the experience. Being immobile and horizontal for several days gives a real sense of relief from the need for action and decision. Being looked after, in every way, is a beautiful inversion for those who spend their lives caring for other people. And being bedridden gives you the chance to contemplate without distraction.

6

There are only four of us in this room. We all seem to be introverts, because not many words flow between us. The older man opposite, who lives across the road from the hospital, has a local accent I find it hard to make out. When I suggest to him and his visiting wife that it must be good to share a given name and an initial with one of the greatest drummers in the history of jazz, they stare at me as if I’m speaking a different language. I feel a fool and say no more.

7

Nurses float by. Sometimes they stop here, to take blood pressure, empty things, or dispense tablets from the ‘sweetie trolley’. They’re usually too busy to chat to, even at the weekend, but one says she’s really a teacher, and works Saturday and Sunday night shifts here to make ends meet and feed her family – a remark that says a lot about the state of the UK in 2022.

8

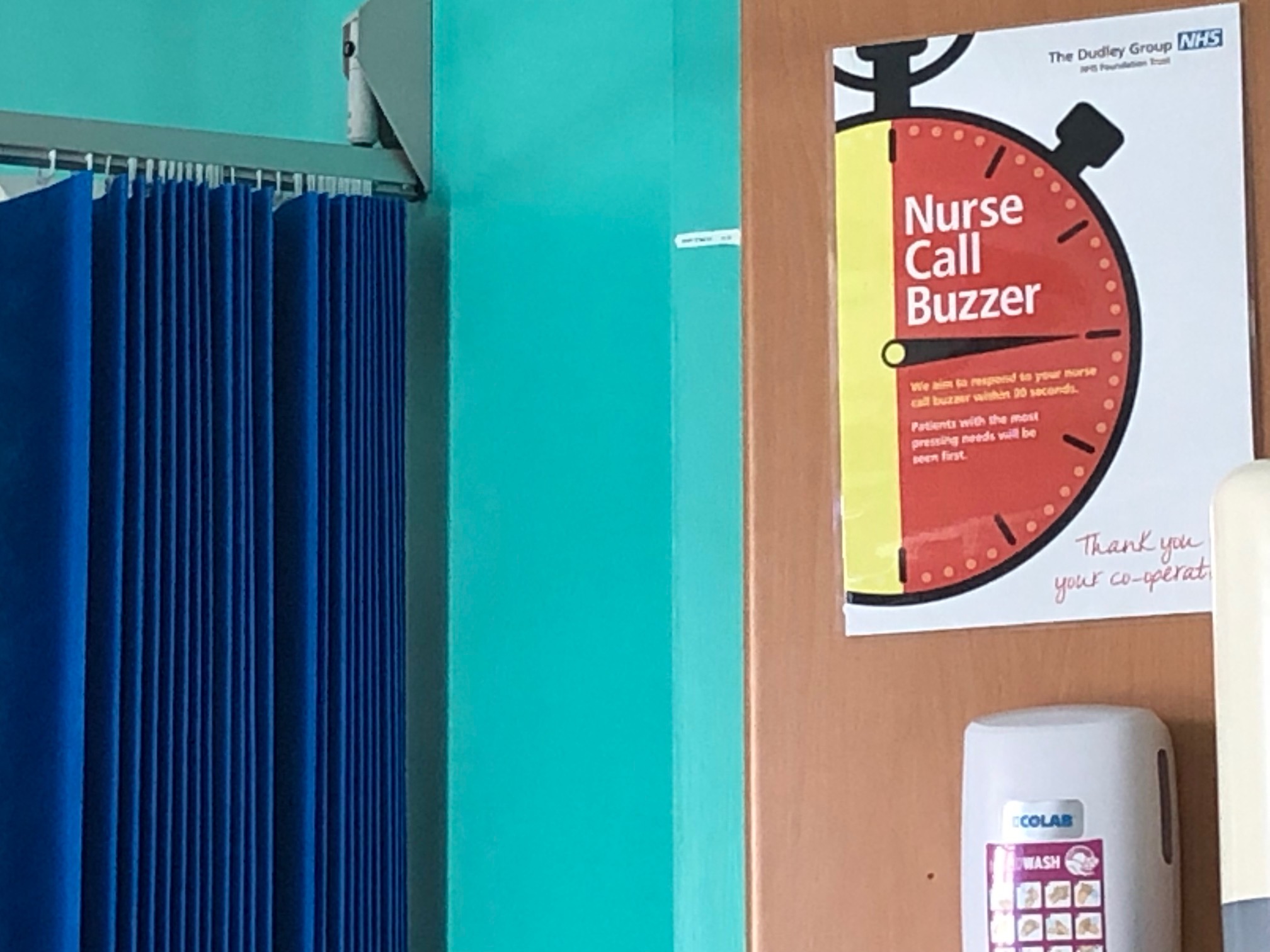

The hospital building is relatively new, and this room is well designed. It’s mostly painted white, but it has doors and panels of turquoise and orange, intended to bring cheer. Ocean-blue blinds, at the windows and as bed-dividers, are blown inwards by the Saharan breeze outside, and give you a vague feeling of relaxing on a cruise ship in balmy tropical waters.

9

The natural world seems far away. Through the window I can see a single tall birch, its leaves already suffering in the drought. It looks like a stage tree, of the kind you might see in a play by Samuel Beckett. The only birdsong I can hear belongs to a pigeon. There’s a constant hum from road traffic; in this part of the country the car is all-conquering king.

10

The ward at night. I’m alone in Room 6: the other three patients have gone home. Sweat collects under my chin, and re-collects as soon as I wipe it away. Light comes through from the quiet nurse station. A single moth flutters. Outside the window, where the ambulances cluster down below, voices chatter and laugh. Laughter, it occurs to me, must be an essential defence in ambulance work. Towards dawn, fitful sleep.

11

Mid-morning, a doctor comes and says C and E can take me home. I get up off the bed, slowly, dress slowly, and wait for bags of medication and dressings to arrive. I’m given a discharge note for my GP. I notice that it calls the operation ‘uneventful’. That result is probably as good as it gets. For me, though, the whole hospital experience has been full of event, to be stored in the memory, and a reminder that the NHS, underfunded and detested by the Tories, is still something to be cherished. It also leaves me with the uncanny feeling that this stay might be a rehearsal for another, rather different experience sometime in the future.

Leave a Reply