This week we spent a few hours in Avebury in Wiltshire. The modern village sits beside (and partly upon) the largest Neolithic stone circle in Britain. It was my first visit since my parents took me to see it in the late 1950s or early 1960s. The stones left a lasting impression on my child’s mind. Returning, I could immediately understand why.

Since 1943 the whole site, including the village, has belonged to the National Trust, which has preserved it well, at the expense of ruthlessly imposing its standard, tasteful upper-middle-class ambience.

But the site’s large enough to absorb the large numbers of visitors who arrive every day. And as we wandered anticlockwise around the stones and the bank that borders the internal ditch, I felt, like most visitors, a sense of wonder –at the circle’s huge ambit, at the mass and cragginess of the biggest boulders, and at the ambition and organising skills of the monument’s builders. Today we’re probably more appreciative than earlier generations, thanks to the work of archaeologists in Wiltshire, Orkney, Ireland and elsewhere, of the sophistication and societal cohesion of Neolithic communities in the British Isles.

Much more is known now about the development, construction and dating of the various phases of Avebury, with its three stone circles (two lie inside the main one), and how it linked to contemporary sites nearby, including the West Kennett barrow, Windmill Hill and Silbury Hill. Discoveries are still being made. In 2017 research revealed, within the southern smaller circle, a hidden rectangular stone alignment, dating possibly to around 3,500 BCE.

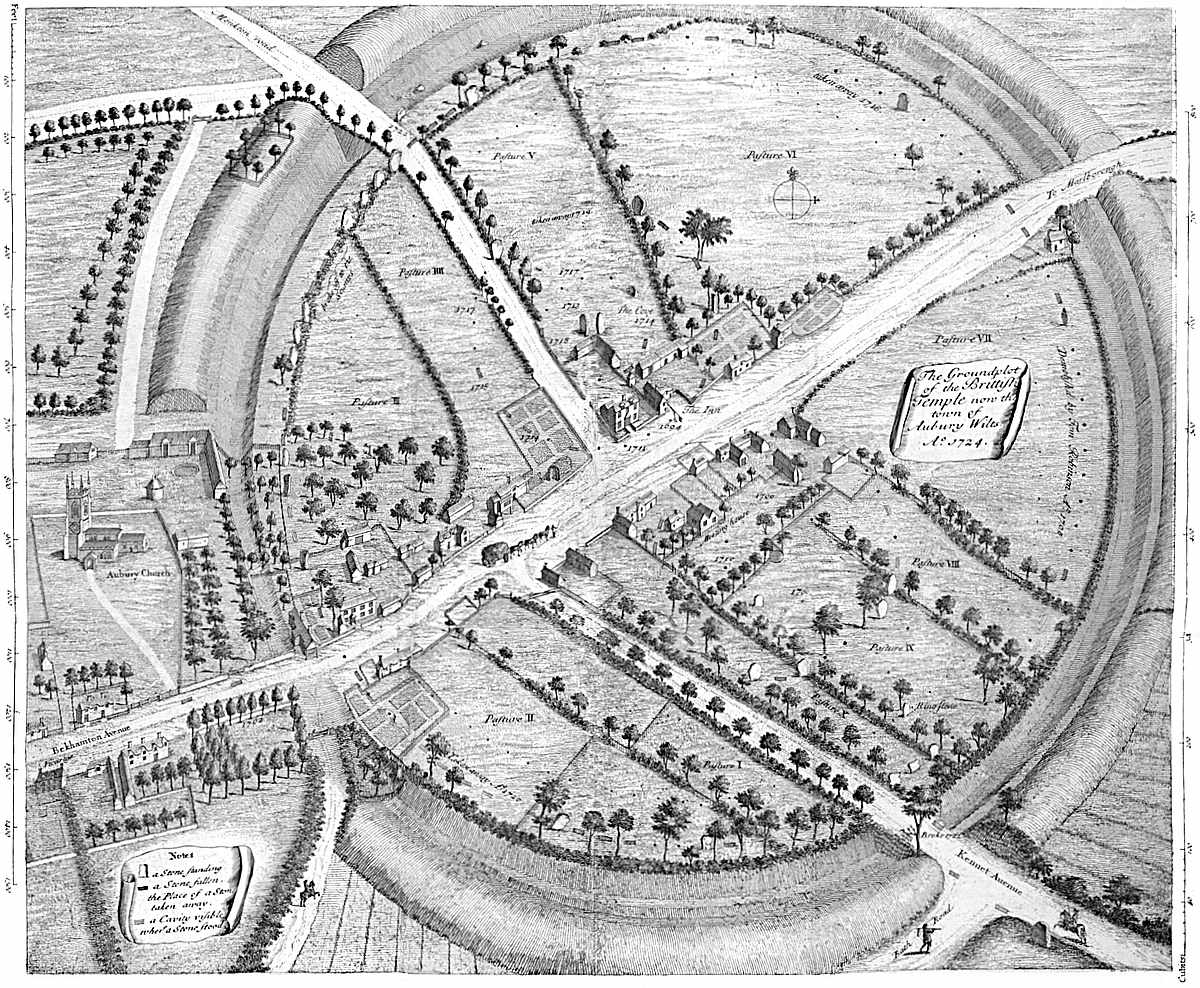

But then there’s what we don’t know about Avebury. That includes answers to the first and most obvious question people ask about the site: ‘what was it for?’ William Stukeley, one of the first to draw attention to the circle after many visits between 1719 and 1724, had his answer: it was a ‘British temple’ build by the Druids in the first millennium BCE. Thomas Twining had another, believing that the Romans were responsible. Modern pagans have various ideas. (As we walked, a woman, presumably a kind of pagan, took up a position before one of the stones and began a kind of wail or howl.)

Such theories have long been dismissed, and new theories have taken their place. But they’ve not been replaced by new knowledge. It’s striking that answers to the ‘what is it for?’ question still revolve around the same limited vocabulary that has been around for many decades. So, in reading modern accounts you often come across words like ‘ritual’ and ‘ceremonial’ – words that cover a lot of ground without committing their users to identifying what rite or what ceremony might be involved. English Heritage, responsible for conserving the monument, must have thought hard before coming up with this verbal equivalent of throwing your arms in the air:

… the various monuments may have been built as public ‘theatres’ for rites and ceremonies that gave physical expression to the community’s ideas of world order; the place of the people within that order; the relationship between the people and their gods; and the nature and transmission of authority, whether spiritual or political.

How could it be otherwise? Archaeology has developed into a highly specialised and scientific interrogation of the material remains of prehistoric societies (or at least the remains that survive), but it rarely has the means to reveal anything certain about their non-material aspects – their belief systems and religions, their social conventions and practices, their poetry and music. Schools of archaeology – processualists, post-processualists and cognitive archaeologists – have come and gone, but the problem remains.

You can look at the stones for a long time: gaze at them from a distance and take in their different sizes and shapes, or get up close and peer at the pits, whorls and fractures in their surface. But there’s always that frustrating gulf between wonder and knowledge. An old archaeology book had the title The mute stones speak. The trouble is that stones don’t speak. They really are silent about what they’re doing where they are.

So we’re left with a choice. We can continue to reflect back on to Neolithic societies those beliefs and religious practices that appeal to us, like the modern pagans, or borrow insights from anthropologists and re-export them to the distant past. Or we can accept that we’ll never be able to get close to the belief systems of Neolithic people, and that there are impassible barriers to the progress of scientific knowledge about the distant past.

(The only thing we probably shouldn’t do, in choosing our inadequate vocabulary to characterise the Neolithics, is to use the word ‘primitive’: a hangover from when all preliterate societies were assumed to lack all sophistication.)

My feeling is that we should let our Neolithic ancestors keep their secrets. They’ve left enough behind them to excite our admiration, and we should admire them – and let ourselves be overcome by the wonder of the stones – even if the National Trust has surrounded them with a cosy, Midsummer Murders set.

Leave a Reply