What comes to mind when you think of a contemporary art gallery? Probably, big empty spaces, clean geometric vistas, minimal signing, white walls. The Museo de Serralves in Porto, Portugal’s main centre for modern art, meets all those expectations, and many more. Its new building was opened in 1999. The designers not only had a compelling central vision, they took great care to get every detail right. As you wander round, inside and out, the building makes you sigh with the pleasure of its visual effects. The galleries are striking and varied, but the smaller spaces are even better, especially the library, whose reading room is dominated by a forest of enormous electric light bulbs hung at different levels, and by a large plain rectangular window looking out on to the park outside.

What comes to mind when you think of a contemporary art gallery? Probably, big empty spaces, clean geometric vistas, minimal signing, white walls. The Museo de Serralves in Porto, Portugal’s main centre for modern art, meets all those expectations, and many more. Its new building was opened in 1999. The designers not only had a compelling central vision, they took great care to get every detail right. As you wander round, inside and out, the building makes you sigh with the pleasure of its visual effects. The galleries are striking and varied, but the smaller spaces are even better, especially the library, whose reading room is dominated by a forest of enormous electric light bulbs hung at different levels, and by a large plain rectangular window looking out on to the park outside.

The park is large and handsome, and wanders downhill past lakes and a tea house towards farmland. It conceals numerous contemporary sculptures, including a jokey garden trowel by Claes Oldenburg. The one that took my eye, though, is almost deliberately hidden and unsignposted. It’s sited in a marginalised ‘alleyway’ at the side of the museum, between a line of trees and the perimeter wall of the park. It’s by the American artist Richard Serra, and is called ‘Walking is measuring’ (2000).

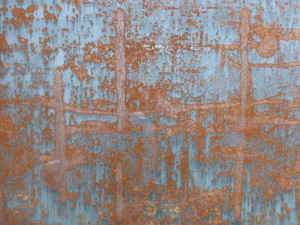

Serra is well known for his monumental metal sculptures, but I’d never before now have called him a ‘walking artist’ like Richard Long and Robert Smithson. The title of this apparently very simple piece certainly stresses the space between the two monumental rectangles of steel Serra has fixed in the ground facing each other, some thirty yards apart.

The two blocks are made of corten steel, so their surfaces have weathered into quasi-organic patterns. Close to, they have an intimate quality. But from a distance each of them has a darker, less human look, accentuated by their concealed, shadowed situation. Together they resemble massive tombstones. The straight walk between them therefore seems to take on a metaphorical significance, as the measured course between life and death. But maybe this is to read into the work an external sign missing from its making. Serra has made similar pieces in the past, like ‘Delineator’ in MOMA, New York, and he acknowledges his debt to the absolutist work of Kasimir Malevich, like ‘Black cross’, a hundred years ago. One of his pieces is called Fernando Pessoa, after the Portuguese writer and inventor of numerous alter-egos or ‘heteronyms’ – a warning perhaps not to inflict single meanings on works of art.

The two blocks are made of corten steel, so their surfaces have weathered into quasi-organic patterns. Close to, they have an intimate quality. But from a distance each of them has a darker, less human look, accentuated by their concealed, shadowed situation. Together they resemble massive tombstones. The straight walk between them therefore seems to take on a metaphorical significance, as the measured course between life and death. But maybe this is to read into the work an external sign missing from its making. Serra has made similar pieces in the past, like ‘Delineator’ in MOMA, New York, and he acknowledges his debt to the absolutist work of Kasimir Malevich, like ‘Black cross’, a hundred years ago. One of his pieces is called Fernando Pessoa, after the Portuguese writer and inventor of numerous alter-egos or ‘heteronyms’ – a warning perhaps not to inflict single meanings on works of art.

Inside the Museum is currently an exhibition of works from the collection of Ileana and Michael Sonnabend. In a section entitled ‘Pop art and nouveau réalisme’ is a large and striking work by Robert Rauschenberg, ‘Kite’ (1963). This is one of Rauschenberg’s collaged silkscreens, with added oil paint. The reproduced images are predominantly images of war: an American eagle at the top, an attack helicopter and a military parade with flags. A faded colour beach scene sits incongruously to the right. But the picture is dominated by the painted elements, a series of thick vertical ‘tubes’. Most are ‘black-tipped’, and from two of them black paint dribbles downwards ominously across the middle, lighter sections.

It’s known that Rauschenberg was hostile to the Vietnam War, and it’s tempting to see this work as a direct critique of US foreign policy or a comment on how conventional patriotism can transmute into aggressive imperialism (the ‘kite’ as predator). But that may be too reductive. Some critics have suggested that Rauschenberg’s work of this period is really concerned with the ‘glut’ or excessiveness of global media and its images. Again, as with Serra’s work, it probably pays to avoid easy conclusions, and to keep the mind free and receptive to multiple meanings.

There is biographical link between the two artists. According to an interview with Serra,

I was thrown out of Yale for something real stupid,’ says Serra, stern features dissolving into a childlike grin. ‘Robert Rauschenberg came up there as a visiting critic. Being a bit sparky back then, I thought I’d see what he was made of. I found a chicken and tethered it to a rope and put it in this box on a pedestal. It was a kind of prank at Rauschenberg’s expense, right? But when he lifted the box, the goddamn chicken flew up above him and started shitting everywhere.

Serra has the reputation of being an austere and remote artist. This anecdote rather belies it. Or perhaps not.

![porto-serra-4536445-o[1]](https://i0.wp.com/gwallter.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/porto-serra-4536445-o1-300x225.jpg?resize=300%2C225)

![01_Rauschenberg_-_Kite[1]](https://i0.wp.com/gwallter.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/01_Rauschenberg_-_Kite1-210x300.jpg?resize=210%2C300)

Leave a Reply