As far as I know, my father produced only one publication. Its title was Notes on making a will and it was a pamphlet of just four pages (a single leaf folded with a white card cover). The publisher, according to the cover, was ‘Bury & Walkers, Solicitors, Barnsley, Wombwell & Leeds’ (Dad was a partner and worked in the Barnsley branch). But he was the real publisher. He had it printed by ‘Derek Hattersley & Son, Hoylandswaine, Sheffield’ – Derek was a printer we knew who lived up in the village, and is still in business. It lacks a date of publication (1985, most likely), and I’m not sure it had a price. My father’s idea, I seem to remember, was to leave copies in the waiting room at Bury & Walkers, in the hope that a client might pick one up and become anxious through reading it – anxious enough to ask him to draft a will for them (conveyancing and will-making were the twin staples of his job.)

I suppose Notes on making a will would now count as a rare book. My brother might own another copy, and there’s a remote chance that one or two others survive in Bury & Walkers’ archives or on the shelves of their ageing clients. A fierce notice Dad had printed on the back cover forbade the making of copies: ‘All rights reserved. Reproduction (in whole or part) without permits from author & publisher is not permitted’. But who knows, an illicit photocopy might lurk somewhere. Being a lawyer, my father would also have known that his pamphlet’s size and print run would allow him to avoid having to send copies to the legal deposit libraries of Britain and Ireland. Nevertheless, he sent one to the British Library, and there it is, listed in the online catalogue. (Possibly I’d persuaded him that this step would grant him immortality, of a kind.)

Notes on making a will is strangely written.

I can’t imagine it drove many clients into the arms of their solicitor. It doesn’t contain a lot of practical advice,

just a few warnings about intestacy and finality, and not even a strong

recommendation to use a solicitor. But

re-reading it I can immediately call to mind my father’s voice, his laconic

expression and slightly out-of-date slang.

The first paragraph gives a good taste of the whole:

Wills are favourites with novelists and playwrights. They are keen on change, preferably sudden, and a sudden inheritance is right up their street. For them the benefit of a will is what a beneficiary gets, and they have little time for a will-maker, except as the benefit’s source: they usually polish him off pretty quick.

At least the pamphlet had one convert. Around the time it was published I had my own will made up. Since then I’ve hardly thought more about it, or about wills in general. But recently I’ve been re-reading a novel in which a will makes a fleeting appearance – though not in the role my father had in mind.

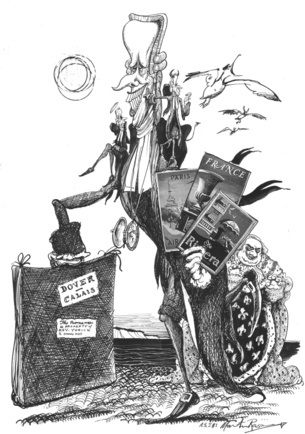

Laurence Sterne’s A sentimental journey through France and Italy, published 250 years ago this year, belongs to (and arguably began) a genre of fiction peculiar to the second half of the eighteenth century – accounts of overseas travels by a ‘man of sentiment’ – a person of refined feelings, more sensitive than the common man to the morals and manners of himself and others. There is no book quite like it. Its narrator is Yorick, the same eccentric parson who lives, and dies, in Sterne’s longer novel, Tristram Shandy. He is, as my father would say, a one-off: impetuous, whimsical, self-absorbed, sensual and sharply aware of his own absurdity, as he rattles his way through France, with his faithful servant La Fleur in attendance, in search of – what, we’re never quite sure, except the seduction and conquest of filles de chambres.

From its famous first sentence, ‘They order, said I, this matter better in France’, there’s a general forward motion in Yorick’s story – each short chapter is headed by a place-name. But his narrative progress, more interested in encounters with people than with the scenery and history of the places visited, is dotted with digressions, anticipations and interruptions of all kinds. One of these mini-stories, entitled ‘The Fragment’, begins with a trivial event.

One morning in Paris La Fleur brings Yorick a pat of butter wrapped in waste paper. Yorick is about to throw the paper away when he notices it contains writing ‘in the old French of Rabelais’s time … in a Gothic letter’. With effort and after several diversions, he succeeds in deciphering and translating the script. The next chapter gives the text of the ‘fragment’: an improbable story about a ‘notary’.

As ‘The fragment’ opens, it’s a dark night, and the lawyer is in the middle of a furious row with his wife, ‘a little fume of a woman’, which ends with her words ‘you may go to the devil’. In a sulk he storms from the house, ‘not caring to lie in the same bed’ with her, crosses the Pont Neuf, loses his hat in the strong wind, and is lamenting his ill luck, ‘at the mercy of the ebb and flow of accidents’, when he hears a voice appealing for a lawyer’s help. In a bare room he finds an ‘old personage’ lying in bed. He sits down beside the bed, pulls out pen and paper, and prepares to draft the decayed gentleman’s last will and testament. But the old man interrupts:

Alas! Monsieur le Notaire, I have nothing to bequeath which will pay the expence of bequeathing, except the history of myself, which, I could not die in peace unless I left it as a legacy to the world … it is a story so uncommon, it must be read by all mankind – it will make the fortunes of your house … It is a story, Monsieur le Notaire, which will rouse up every affection in nature – it will kill the humane, and touch the heart of cruelty herself with pity.

The lawyer dips his pen into his ink, for the third time, ‘and the old gentleman turning a little more toward the notary, began to dictate his story in these words – .’ And there the fragment ends. ‘And where is the rest of it, La Fleur? said I, as he just then entered the room.’ La Fleur rushes out in search of the rest of the waste paper, but in vain. And there the story ends. ‘Whether I [found the text later] or not’, promises Yorick, ‘will be seen hereafter’. Needless to say, we hear no more.

‘The Fragment’ has any number of Sterne’s favourite devices. It’s a good example of his taste for metafiction, a tale within-a-tale (if the fragment had continued, we would have had a tale-within-a tale-within-a-tale). It contains an appeal to ‘sentiment’, in the notary’s willingness to ‘assist the decaying memory of an old, infirm, and broken-hearted man’ and the man’s story that will ‘rouse up every affection in nature’. And there’s another recurring theme of A sentimental journey – thwarted desire. Just when Yorick is on the point of achieving his (passionate and usually erotic) ambition, chance intervenes to frustrate him: the innkeeper returns with the key to the carriage store, just when he’s closing in on the ‘fair lady’ in Calais; he’s ‘taking the pulse’ of an attractive shopkeeper in Paris when her husband appears from the back parlour. So, in ‘The Fragment’, at the very point when Yorick (along with the lawyer) is agog to learn the astonishing story of the old gentlemen, the text runs out and his intense curiosity is left unsatisfied.

The ‘thwarted’ theme is part of Sterne’s satirical intent. A sentimental journey is at once a celebration of the man of refined feelings (feelings that run the gamut from the philosophical to the lustful), and a comic puncturing of the same impulses. But beyond the parody lies a darker, more existential subject, the brute power of blind fate, and its ability to overturn and mock any human plans. ‘The fragment’, itself a chance intrusion into the narrative, is full of random, often bizarrely random, happenings. How the notary loses his hat in the wind on the Pont Neuf is an example. In raising his cane ‘instinctively’, he catches the loop of a sentry’s hat. The hat flies off into the river Seine, and is caught be a passing boatman. The angry sentry levels his ‘harquebuss’. Luckily a passing woman has borrowed his matches to relight a lantern at the end of the bridge, so instead of threatening to fire his weapon he contents himself with removing the hat of the notary, who’s left ‘bare-headed in a windy night’.

A sentimental journey insists on the importance of compassion and benevolent feeling in driving human behaviour, and holds that they derive from – and prove the existence of – a human and divine soul. Sterne attacks fashionable French arguments for materialism from deists and atheistic thinkers like Denis Diderot (whom Sterne had met) and his fellow Encyclopédists. But perversely their world view and what Sterne calls ‘the sport of contingencies’ keep pushing their way into the narrative. The power of circumstance and accident is constantly overriding the desires of humans.

The ultimate accident is death. But death is oddly absent from the narrative of A sentimental journal. This is doubly curious, and little mentioned by Sterne researchers. In Sterne’s first account of travels in France, in Book 7 of Tristram Shandy, Tristram’s motive for his journey is to keep one step ahead of Death, that ‘long-striding scoundrel of a scare-sinner’, and ‘lead him a dance he little thinks of’. Death in one form or another casts a long shadow throughout the novel. Sterne himself went to the continent in 1765 in search of a healthier environment: since his student days he had known that tuberculosis would likely kill him sooner or later. His letters from the years when he was writing his later works are full of references to serious illness, and he died only two weeks after the publication of A sentimental journey. Yet there’s barely a trace, in Sterne’s last book, of the imminence of death (the only hint that Yorick may be fatally ill is in the chapter ‘Versailles: the passport’, where ‘I look’d a little pale and sickly’). It can hardly be a coincidence: what was Sterne’s intention, I wonder?

The book ends, then, not with mortality, but a moment that combines sentiment and erotic desire with complete accident. Yorick is obliged to share a hotel bedroom with a lady and her maidservant. The servant has placed herself in the middle of the three, ‘So that when I stretch’d out my hand, I caught hold of the Fille de Chambre’s End of Vol. 2’. The lack of a full stop leaves open all outcomes, but you’re left feeling that frustration is again the likeliest …

Leave a Reply to Larry Smith Cancel reply