Mansfield Park isn’t, I suspect, the favourite novel of Jane Austen of those who value her for her cutting wit and comforting social outlook. Because, though not without its share of humour, it’s a far from comforting work. It asks questions about how people of strong convictions but introverted character and uncertain social status can succeed, in a world dominated by reactionary materialists and exploitative cynics.

Two other things about the book probably mark it down for Janeites. For much of the story nothing of much consequence happens. And its heroine, Fanny Price, strikes many readers as too passive and featureless to excite much interest or engagement.

Mansfield Park seems an experimental work. Austen doesn’t have much interest in outward events, since the real action takes place almost entirely inside Fanny’s mind. The anxiety and hesitancy that torture her stem in large part from her personal circumstances. She’s effectively adopted – removed at the age of ten from her own impoverished family to live with her aunt and uncle in the country house of Mansfield Park. Here she’s treated as an inferior by her cousins, with the exception of Edmund, who acts as an unofficial guardian. She lives in awe of her uncle, Sir Thomas Bertram, a wealthy plantation owner (and presumably slave-owner), and feels keenly the hostility of his sister-in-law, Mrs Norris.

As a result, over the next years Fanny learns to keep her real opinions to herself, and to withdraw herself from the scene (literally, in the case of the amateur dramatics that the Mansfield Park youngsters stage in Sir Thomas’s absence in the Caribbean). But she’s a keen observer of the actions, behaviour and ethics of those around her – especially in the case of Henry Crawford, a family friend who takes a strong interest in Fanny, although not until he’s played, unsuccessfully, with the affections of her cousins, Maria and Julia. The keystone of the novel is Chapter 31, where Crawford, having helped Fanny’s beloved brother William gain promotion in the Navy, presses Fanny to marry him. For the first time in the story, Fanny acts with fierce decisiveness. She rejects him. And she continues to reject him, even though Crawford redoubles his efforts to win her, and even though her family, including Sir Thomas, take his side and pressure her to yield.

Unlike the rest, Fanny sees through Crawford’s plausible exterior and is unimpressed by his wealth and supposed favours. Her determination to spurn him stems from an innate and strong sense of personal virtue that overrides more material considerations (some have suspected that Austen imported into her some of the characteristics of the new evangelical Christians influential at the time she was writing).

Fanny’s stand is vindicated when the news arrives from London, much to the horror of the Mansfield Park family, that Crawford has renewed his sexual relationship with Maria, seduced her away from her husband and eloped with her. After that, Austen seems to lose interest in her own story. In a final, rather perfunctory chapter, he lets Sir Thomas and the others recover quickly from the emotional shock and social scandal of the seduction and elopement, and marries Fanny off to Edmund, now a cleric – disappointingly, for readers looking forward to seeing a newly confident and independent Fanny emerging.

Austen takes risks with Fanny. It’s almost inevitable that shutting herself into her own mind until the ‘Crawford moment’, rather than granting her agency to act in the world, will try the reader’s patience. The rigidity of her moral principles, too, does little to endear us to her. Her objections to the amateur dramatics as ‘improper’ can seem extreme – until you realise that she fears that the play offers the cast the chance to act out their illicit desires (Maria and Crawford, Edmund and Crawford’s sister).

It occurred to me, when I reached the end of the book, to wonder how illustrators, especially modern illustrators, tried to imagine Fanny Price in visual terms, given the lack of authorial clues and her absence of distinguishing features. (Austen goes out of her way to refuse us an initial view of Fanny: ‘there might not be much in her first appearance to captivate, there was, at least, nothing to disgust her relations’.)

Publishers have clearly had a hard time, over the years, in knowing what picture to put on the covers of their editions of Mansfield Park. Some avoid the Fanny problem altogether, often by adopting a decorative design. Penguin once chose a painting of a grand country house (not a bad choice, given that Mansfield Park, the house and its estate, are virtually additional characters in the novel). Another old Penguin edition, for some reason, features Sir Thomas Lawrence’s painting of the young children of Sir Samuel Fludyer, which seems of only peripheral relevance to the novel.

Other publishers, like Oxford UP, do try to grasp the nettle, using a variety of period paintings showing suitably demure, solitary young women. The most successful of these is the current Penguin Classics edition, which shows Louis-Eugène Larivière’s sensitive Portrait of Eugénie-Paméla Larivière. Eugénie (the artist’s sister) conveys the air of a reserved but resolute woman. The Vintage illustrator invents a stylised Fanny figure, turning away from the disparaging comments of her two female cousins. A much bolder image appears on a Phoenix edition, showing a thorn-bound family group (oddly, in late Victorian dress), with a black bird soaring overhead.

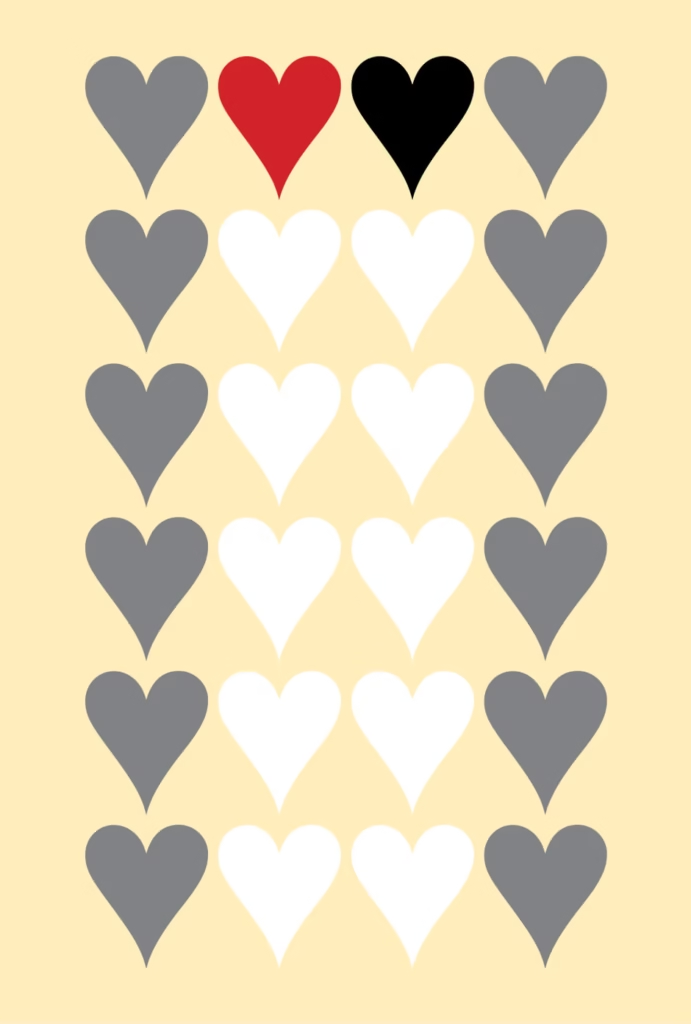

Perhaps it was the difficulty of hitting on suitable images for Mansfield Park that persuaded the Folio Society in 2016 to hold a competition among illustrators for its new edition, published in September 2017. Twenty-three finalists, from all corners of the world, were selected. Their designs were varied and imaginative. Perhaps the most striking were Pedro Silmon’s illustration of Fanny and Crawford dancing – a hearts playing card, with the two dancers coloured red and black – and Alexandru Savescu’s depiction of Fanny, blue in distress. The competition winner was a Russian artist, Darya Shnikina, whose decorative, angular and uncomfortable images make apt companions to the text. They come as close, maybe, as any illustrator could to the strange and paradoxical nature of Mansfield Park and its heroine.

Leave a Reply