It wasn’t his real name, ‘John Ystumllyn’, but one the locals gave him. Another was ‘Jac Du’ or ‘Jack Black’. How he arrived, unwillingly, in north Wales is obscure. What is certain is that his origins were in Africa, and that he found a home for himself and his family in the Criccieth area in the second half of the eighteenth century.

Africans were by no means unknown in Britain at the time. The triangular transatlantic slave trade, it’s true, spared most Britons the sight of slaves. They were shipped direct to the Caribbean, and, if they survived the crossing, that’s where they stayed, typically working on sugar plantations. It wasn’t the slaves but the profits from trading in them and exploiting them that streamed in a rich flow into Britain, as you can follow in great detail with the help of the excellent Legacies of British slave-ownership database in University College London. Nevertheless, some slaves did come to London and other centres, as a fashion arose among aristocrats and wealthy landowners for keeping black servants. They were often used as pageboys, coachmen or musicians, serving as exotic emblems of their owners’ taste and cosmopolitanism.

Wales very occasionally shared in this vogue: in the later eighteenth century the squire of Erddig near Wrexham had a black horn player in his local band, and had his portrait painted. Other black people, servants to less exalted owners, were scattered across the country. David Morris has found 29 names of black people listed in parish registers in south Wales between 1687 and 1814. Undoubtedly more remain to be discovered, including in north Wales. But their absolute numbers were small. When John Ystumllyn came to Eifionydd he was regarded by most as a wonder.

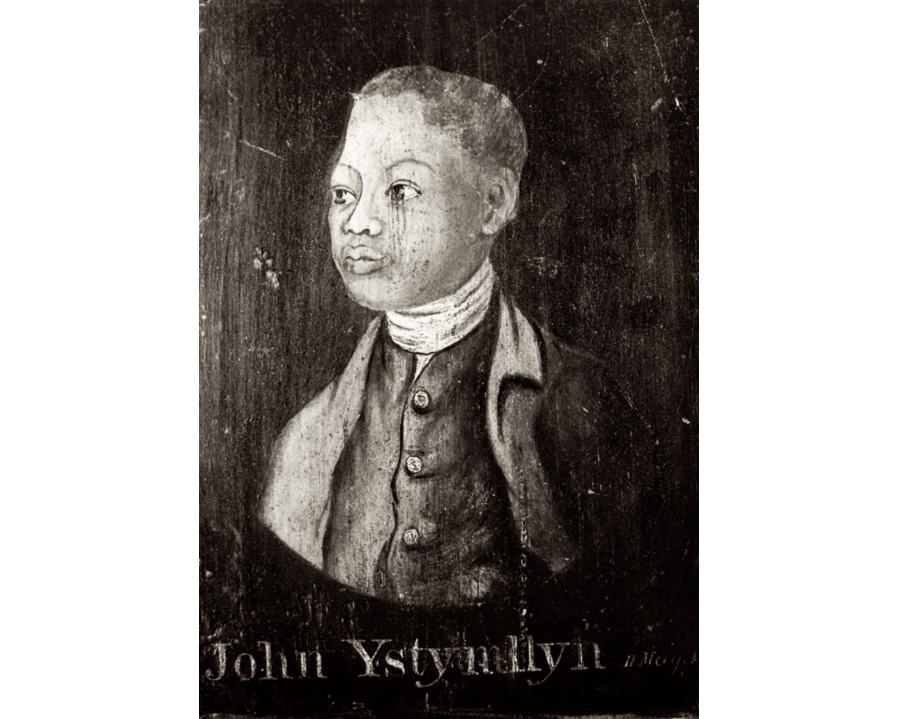

We know about John from three sources, all of them remarkable. A small oil painting on wood, in private hands, shows his portrait as a young man. The unknown artist names him, ‘John Ystymllyn’, and adds a date, 11 May 1754. John wears a jacket and buttoned waistcoat, and a neckband – standard dress for a working man of the period.

When John died in 1786 he was buried in the churchyard at Ynyscynhaearn, between Pentrefelin and Criccieth – the church and churchyard are now in the care of the Friends of Friendless Churches – and a memorial stone was later raised. The inscription on it (which misdates his death to 1790) includes an englyn written by Dafydd Siôn Siâms of Penrhyndeudraeth (1743-1831), who was a carol- and hymn-writer as well as a poet (my transcription, made in July 2018, and translation):

Yn India gyna fe’m ganwyd – a ngamrau

Ynghymru medyddiyd;

Wele’r fan dan lechan lwyd

Dy oeredd im daerwydBorn in India, to Wales I came

To be baptised

See this spot, a grey slate marks

My cold resting place

The third source is the most informative – a pamphlet, published in 1888, entitled John Ystumllyn, neu, ‘Jack Black’ : hanes ei fywyd, a thraddodiadau am dano, o’r amser y dygwyd ef yn wyllt o Affrica hyd adeg ei farwolaeth; ei hiliogaeth, &c., &c., ynghyda darlun o hono yn y flwyddyn 1754. An English version was published in Cricieth in the 1960s or 1970s, as John Ystumllyn or ‘Jack Black’: the history of his life and traditions about him since his capture in the wilds of Africa until his death; his descendants, etc. etc., together with a picture of him in the year 1754. The picture in the Welsh pamphlet was a woodcut of the original oil painting.

The third source is the most informative – a pamphlet, published in 1888, entitled John Ystumllyn, neu, ‘Jack Black’ : hanes ei fywyd, a thraddodiadau am dano, o’r amser y dygwyd ef yn wyllt o Affrica hyd adeg ei farwolaeth; ei hiliogaeth, &c., &c., ynghyda darlun o hono yn y flwyddyn 1754. An English version was published in Cricieth in the 1960s or 1970s, as John Ystumllyn or ‘Jack Black’: the history of his life and traditions about him since his capture in the wilds of Africa until his death; his descendants, etc. etc., together with a picture of him in the year 1754. The picture in the Welsh pamphlet was a woodcut of the original oil painting.

Its author was Alltud Eifion, the bardic name of Robert Isaac Jones (1813-1905), a Tremadoc chemist, printer, publisher, poet and editor. Jones’s grandfather had been the doctor who cared for John Ystumllyn at the end of his life, and oral traditions about John had clearly passed down within the family. Like most oral traditions they were prone to variation, embroidery and forgetfulness, and Alltud Eifion’s account is frank about the uncertainties of John Ystumllyn’s remarkable life.

He’s unclear about how John came to the Criccieth area, and relates three separate stories. One was that ‘one of the family [the Wynne family of Ystumllyn, possibly Ellis Wynne], who had a yacht, caught the boy in a wood in Africa and brought him home to Ystumllyn’. The second tradition told how ‘Ellis Wynne of Ystumllyn’s sister, who lived in London, sent him as a gift to her brother’. And the third was a story apparently told by John himself, how ‘he was on the banks of a stream amid woodland attempting to catch a moorhen when white men arrived and caught him and took him away with them to the ship’.

It’s not inconceivable that Wynne was directly implicated in the slave trade, but it’s much likelier that John came from a slave family in the West Indies, the origin of many Africans in Britain. This would explain the word ‘India’ in the memorial englyn on his epitaph. When he arrived, and at what age, is also uncertain. According to Alltud Eifion he may have been eight, thirteen or even sixteen.

He twice refers to John’s speech: ‘he had no language, only something akin to a howl, or screams’, and ‘he had no language other than sounds similar to the howling of a dog, it was difficult to decide what age he was’. (Presumably he spoke a West African language.)

At first John was frightened, and the family ‘had considerable difficulty for a long time in domesticating him, and he was not allowed to go out; but after some efforts by the ladies, he learnt both languages [Welsh and English], and he learnt to write’. He was also baptised, in Ynyscynhaearn or Criccieth.

Alltud Eifion continues,

He was placed in the garden to learn horticulture, which he did more or less perfectly, as he was very ingenious. He could turn his hand to almost anything he saw someone else do, such as making small boats, wooden spoons, wicker baskets etc. He was also very fond of flowers and a good florist.

He grew into a handsome and vigorous young man, and although he was black in colour, the young ladies of the area doted on him and there was much rivalry between them in order to get John as a suitor! When he was at work in the garden, John would get some bread, cheese and ale from the Plas, at a specific time of day, and the maid, namely Margaret (who later became his wife) would be sent to deliver the meal to the garden. But she was so afraid of the black man that she used to leave the food and drink in a corner of the garden, running away quickly. But it was she who, in time, became his wife! And as there is no accounting for young women’s taste (fancy) in their menfolk, neither can it be guessed why the women of the area contended with each other for “John Ystumllyn”.

At Ystumllyn, a maid, Margaret Gruffydd, from Hendre Mur, Trawsfynydd, would bring him bread, cheese and ale each day. She was too frightened of him to speak: she would leave his lunch in a corner of the garden and run away immediately. But eventually she overcame her fear and began a relationship with him. When she moved to work in nearby Ynysgain Bach, and later moved again to serve the minister’s wife in Dolgellau, John followed her (losing his post in Ystumllyn). The two were married in Dolgellau church on 9 April 1768. The best man, Griffith Williams, was the son of the vicar who presided.

John and Margaret then lived at Ynysgain, where they were employed as ‘land stewards’. Towards the end of their life, when John worked at Maesyneuadd near Talsarnau, another Wynne home, they lived in a cottage called ‘Y Nhyra Isa’ or Nanhyran, ‘which was given to John together with a small field in front of the house. Ellis Wynne, Esq., gave him possession as recognition for his service’. Margaret and John had seven children, five of whom grew to adulthood, and some of their descendants still lived in the area in Alltud Eifion’s time. The only son was Richard:

Richard Jones was very keen on hunting, and followed the gentry of the area at the Hunts, as was usual in this part of the country at that time; and when he grew up, became Huntsman to the Honourable Lord Newborough of Glynllifon, and served him for a lengthy 58 year period. He lived in a place called Cae’r-geifr, Llandwrog. He was a tall, calm man, who wore a Top Hat, Velvet Coat with a high white collar around his throat. After he was overcome by old age, he gave up his job and Lord Newborough gave him a pension as long as he lived; he has family remaining in Llandwrog. He was a quiet, gentle man who had no malice in him; he died aged 92 in the year 1862 and was buried in Llandwrog cemetery, although his great desire was to be buried in his father’s grave at Ynyscynhaiarn.

Alltud Eifion ends his account with some reflections about John’s character and reputation. ‘John was a very honest man, with no malice, and was respected by the gentry and the common people alike.’ ‘He told a neighbour of his when he was on his deathbed that his main regret was that he played the crwth (fiddle) on Sundays at Ystumllyn and Maesyneuadd’. Although the presence of a black man in Gwynedd inevitably aroused surprise and even shock, there’s no suggestion that anyone held racist attitudes towards John. On the contrary, one anecdote related by Alltud Eifion reveals much about at least one person’s ‘blindness’ to ethnicity:

The late Ellis Owen, Cefnmeusydd, use to relate an interesting story about Margaret Jones, y Nhyra, at Penmorfa Fair when Richard her son (Richard Jones, Huntsman, Glynllifon, later) was around 2 years old, and she took him on her arm on the afternoon of the Mayday Fair, as was the practice in those days, and John Ystumllyn went to the Fair in the evening. The child saw his father a distance away and shouted ‘Dada, Dada’; then his mother said to her friends “have you seen such a smart child as this one, recognising his father among so many people,” without considering that his father was black as soot in the midst of white people; as the old adage says – “The crow sees its chick as white” (‘Gwyn y gwêl y fran ei chyw’)

When so many early black inhabitants of Wales have left little or no trace of their lives to us, it’s good to know even a little about one of them, who can now stand alongside better-known black figures from eighteenth century England, like Dido Belle, Ignatius Sancho and Francis Barber.

It’s worth going to Ynyscynhaearn – by foot from Pentrefelin – to visit John Ystumllyn, and other notables buried there with him, including the harpist and composer David Owen (Dafydd y Garreg Wen), the antiquary Ellis Owen, the poet and blacksmith Ioan Madog – and John Ysyumllyn’s remembrancer, Alltud Eifion.

Afterword (July 2012).

A black visitor to Dolgellau in 1797 had a very different reception from that given to John Ystumllyn:

On our return to Dolghelly, we found the town in an actual state of riot and confusion; we could not approach our inn, for the croud of surrounding peasantry. On inquiring into the occasion of this tumult, we were informed that a Gentleman had just arrived, with – a black servant! This phenomenon had set the Welsh in an uproar, it being the first time such a tinted being had made his appearance here: the poor fellow was persecuted by them wherever he went, and both his master and him were actually forced to continue their route sooner than they intended, in consequence.

Henry Wigstead, Remarks on a tour to north and south Wales in the year 1797, London, 1800, p.48.

This article was updated in December 2018 and July 2021. An article based on it appeared in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography in October 2019.

Leave a Reply to Andrew Green Cancel reply