Last week I was felled by a mysterious (non-Covid) illness. The doctor’s best guess was that it was caused by ‘Virus X’, a hard-to-pin-down invader that was powerful enough to wreak temporary havoc with my body. (My father-in-law, who was also a GP, would have written on my notes the letters ‘SKV’, short for ‘Some Kind of Virus’.)

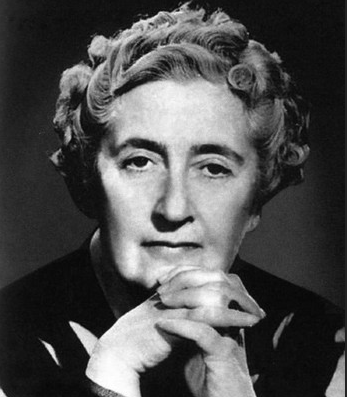

I was feeling so wiped out that I could barely move a muscle. The best remedy seemed to be to read a detective story from the classic period. I turned to Agatha Christie’s 1936 Hercule Poirot novel, The ABC murders. It concerns a serial killer who has, as the title implies, an unusually alphabetical approach to identifying his victims. The plot, as you’d expect, is ingenious – one reviewer called the story ‘a baffler of the first water’ – but the truth, as revealed by Poirot, fails to convince, and the characters, as often in Christie, are one-dimensional (Poirot, with his cod-French and portentous air, is his usual irritating self). Sarah Phelps’s 2018 television version of The ABC murders wisely took some liberties with the Christie plot.

After the first murder, in Andover, the perpetrator sends Poirot a second letter, warning about an imminent death in Bexhill. A conference is called in the town, attended by Poirot, the Chief Constable and various other local policemen, and someone introduced as ‘Dr Thompson, the famous alienist’. Christie gives us a quick portrait: ‘Dr Thompson was a pleasant middle-aged man who, in spite of his learning, contented himself with homely language, avoiding the technicalities of his profession.’

So what was Dr Thompson’s profession? In short, an alienist was what we’d now call a criminal or forensic psychologist.

The Oxford English Dictionary gives this definition of alienist: ‘a psychiatrist; (in later use chiefly) spec. one who specializes in acting as an expert in court to assess whether a defendant is sane and can therefore be held criminally responsible for his or her crime’. The term was borrowed from the French aliéniste in the mid-nineteenth century. One quotation from 1864 reads, ‘a distinguished alienist, and Member of the Belgian Lunacy Commission’ (maybe an ancestor of the Belgian M. Poirot?).

Dr Thompson’s role in the police conference is obviously not to assess the sanity of the criminal, who still has a further two murders to commit before being identified, but to build a psychological profile of the murderer. You could hardly say his interventions are acute. He offers the thought that a madman can yet possess a ‘deadly logic’, but wonders whether the alphabetic order could be accidental.

Thompson turns up again in a second police conference, after the Bexhill murder has happened. Again, his observations are far from startling. ‘He won’t look like a madman’, he assures the meeting. When asked whether the details of the murders should be made public, Thompson is defeatist: ‘one way you feed his megalomania, the other you balk it. The result’s the same. Another crime’. Later in the conversation he asserts that a madman kills not at random, but either to remove obstacles to him, or by conviction. ‘We can tell better, of course, after the next murder.’ This helpful comment provokes an outburst from the Assistant Commissioner: ‘for God’s sake, Thompson, don’t speak so glibly of the next crime’. Thompson ‘held his peace and blew his nose with some violence. ‘Have it your own way,’ the noise seemed to say. ‘If you won’t face facts –‘.

Christie has an interest, of course, in painting her police as pedestrian bumblers, but she doesn’t treat Dr Thompson much more favourably. No doubt she was a sceptic about the validity of current psychological theories of criminal motivation. But, more important, her plot relies not on the alienist’s detection of a manic murderer, despite all the encouragement she gives us throughout the story to believe that a crazed mind is at work, but the pursuit and unmasking of an entirely rational and ruthless criminal. In the end, for the classic whodunnit, the alienist is redundant.

Christie’s ‘alienist’ has evolved into the contemporary forensic psychologist, equipped with many more evidence-based tools than were available to Dr Thompson. The French word aliéné (‘madman’) derives from the Latin alienus (‘other’). Today both madness and otherness are concepts of limited use in understanding criminal behaviour. The ‘alienist’ lives on only in historical fiction, as in the case of the figure of Dr Laszlo Kreizler, a psychologist in late nineteenth-century New York, in Caleb Carr’s 1994 novel The alienist, made into a television series of the same name in 2018.

Leave a Reply to Terence McLoughlin Cancel reply