In 1940 the government commissioned around sixty artists to record local scenes all over Britain, in order to capture a visual record of the country’s buildings and landscapes before they were transformed by the effects and aftereffects of war. The scheme, labelled ‘Recording Britain’, became a home equivalent of the war artists scheme set up in 1939. (In 1941 it was joined by a photographic equivalent, the National Buildings Record.)

The idea came from Kenneth Clark, Director of the National Gallery. Inspired by the Federal Art Project in the US, he intended it as a reminder of the national inheritance that the war was being fought to defend, and as a way of giving employment to needy artists. Clark and his committee persuaded the Pilgrim Trust to fund the programme, and they selected the artists, some established, some younger. They gave the artists guidelines: they were to work, for example, in watercolour rather than oils, and were to give attention to churches and country houses. The resulting 1,500 paintings and drawings were exhibited widely during the war years, and in 1949 were donated by the Pilgrim Trust to the Victoria and Albert Museum (you can see images of them on the Museum’s website).

The reception of the works wasn’t entirely positive. Critics found many of them of conservative and nostalgic style and of mediocre quality. Glancing through images of them today tends to reinforce that judgement. But there were exceptions. Among the artists was John Piper, whose paintings combined architectural exactitude and revived romanticism. Another was Kenneth Rowntree. For him, the Recording Britain project seems to have acted as a spur to his artistic development, and, in his own words, ‘a great self-education’.

Rowntree was in his thirties when he joined Recording Britain. He was born in Scarborough and went to school in York. At the Slade School of Art, he had met Eric Ravilious and Edward Bawden, and later worked with them in Great Bardfield in north Essex. As a Quaker he would not fight in the war, and Recording Britain gave him a role and a small income. The scheme allotted several areas to him: Bedfordshire, Essex, Yorkshire, Derbyshire, Merioneth and Caernarvonshire.

‘Britain’ generally meant ‘England’, as so often. Northern Ireland was excluded, Scotland had its own scheme, and Wales was only covered in part. Several artists worked on the Welsh counties that were included, including Mildred Eldridge in Denbighshire, Montgomeryshire and Merioneth, Mona Moore in Glamorgan and Merioneth and Frances Macdonald in Caernarvonshire and Merioneth. The pictures Rowntree painted stand out from the rest, for their style and their choice of subject.

He generally avoided the standard views and sites made familiar by two centuries of visiting artists in Wales. Conwy Castle appears in one scene, but its walls and towers are dominated by an upturned coracle and a waterside shed. Steered towards religious buildings, he prefers obscure or remote examples, like the New Church (not the old one) at Llangelynin in Dyffryn Conwy and Gwydir Uchaf Chapel. In other pictures, like ‘Council chamber, Municipal Offices, Bangor’, he finds his way to locations other artists would never dream of exploring. Choices like these point to a spirit of sympathy with the hidden places of Wales and its people. Rowntree is also aware of lesser-known episodes in Welsh history: his choice of Tan-yr-allt, Tremadog is surely informed by a knowledge of Shelley’s disastrous stay there in 1812-13. Swan Cottage in Rowan is a characteristic but entirely unremarkable example of vernacular architecture.

Rowntree’s style, too, is different. It departed from the essentially nineteenth-century-derived style of most of the other artists in the ‘Recording Britain’ programme. His art education and personal preference inclined him to a gently modernist approach to landscape. ‘Capel Tremadog’ is a good example, with its flattened and simplified façade, prominent five-bar gate and block-like wall, trees and sky, and its restricted range of colours.

Wales had clearly worked its way into Rowntree’s artistic world, because shortly after the end of the War he was commissioned by Nikolaus Pevsner to create twenty colour images for a new King Penguin book, A prospect of Wales. Pevsner was the general editor of this series of ‘illustrated keepsakes’, and was presumably aware of the quality of Rowntree’s work in Wales. The images were to accompany an essay by Gwyn Jones about Wales, though the title page of the book, when it appeared in September 1948, makes it clear that Rowntree’s work was the primary element.

Rowntree designed tromp l’oeil covers of A prospect of Wales, showing a portfolio of paintings (and a palette) with a Welsh mountain scene behind. The plates inside continue the variety and moderate modernist style of the wartime works. They extend Rowntree’s range into mid and south Wales, and include a few urban scenes, like a terraced street in Neath, as well as rural ones. Again, the themes and viewpoints tend to be unexpected. For example, most artists visiting Devil’s Bridge in Ceredigion chose the Mynach waterfalls and the three superimposed bridges as their focus. In Rowntree’s version, by contrast, the falls are only visible in a miniature frame, through the window of a hotel bedroom, itself dominated by a large wooden chest of drawers.

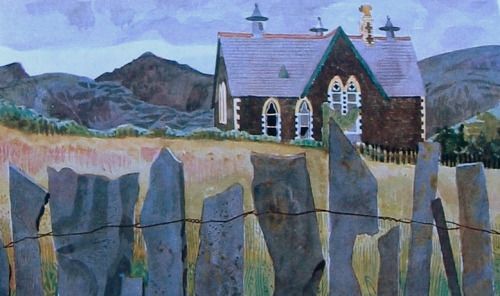

One of the most successful images in the book is ‘School at Upper Corris, Merioneth’. Here the mundane school building is situated geographically and culturally: Cader Idris rises in the distance, and a row of ‘crawiau’, vertical slates tied by wires to form a fence, stretches across the foreground (Stanley Spencer had used exactly the same device ten years earlier in his Llanfrothen painting ‘Landscape in north Wales’). One critic wrote that ‘the illustrations show Rowntree at his best: taut, economical, with a feeling for the geometry in landscape’.

Another publication of 1948 carried an image by Rowntree: the cover of a novel, Wennon, by Cledwyn Hughes, a now largely forgotten Welsh novelist and travel writer.

Kenneth Rowntree later had a successful career as an artist and an art educator, becoming professor in the art school at Newcastle University, where other staff included Victor Pasmore and Richard Hamilton. For a time, his style became more austere and constructivist. One of these later works, his first print, is evidence for his continuing interest in Wales and Welsh subjects. Entitled ‘Welsh print’, it features five (almost) contiguous rectangles, of different homogeneous colours, and a sixth, taken from a Welsh-language newspaper. He said of it, ‘I tried to evoke a feeling that I hold for Wales and things Welsh, not only by the hint of the Welsh script, but also by the individual colours.’

In the catalogue of a centenary exhibition in 2015 John Milner summarised Rowntree the artist thus: ‘He was a lover of what was particular and unique in whenever, whatever, or whoever was before him, and he resolved all this in a sensual and intellectual game of variations that consistently delight both eye and mind.’ Wales played a seminal role in that vision.

Leave a Reply