‘Still life’ is a paradox. Can something that’s still or unmoving be alive, especially if it’s a dead creature or an inanimate object? The French equivalent, nature morte, is equally stark in its self-contradiction. But the term isn’t the only paradox. One of the reasons why the still life has had such a long history, right up the present day, is that it’s so full of potential for ambiguity and subtlety.

The Dutch invented the still life (still-leven) as a distinct form of painting in the ‘golden age’ of the seventeenth century. From the start they linked it with the warning that all living things must die, and (good Calvinists that most of them were) with the injunction that we should therefore look to our own moral behaviour and our chances of a good life after death. So, although the glass goblets may be the finest available and the food exquisitely prepared, flower petals are already starting to brown and wilt, over-ripe grapes have dropped from their bunch, and a butterfly, ephemerality embodied, flits above the food. And yet, paradoxically, the finest painters of the Netherlands lavished enormous care on their still life canvases, as if they were confident that their works would withstand the predations of time.

A few Dutch still lives mark the start of the current exhibition in the Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, ‘The shape of things: still life in Britain’. (‘Britain’, as so often in English exhibitions, means ‘English’: there’s only a handful of Scottish works, and none from Wales or Northern Ireland.) It’s a high-quality and thoughtful show, arranged in rough chronological order. It seems to gather pace as it approaches our own era: a sign that still life, despite its apparently limited range – it ranked below all other genres in the eighteenth-century hierarchy of painting – still holds a strong visual and conceptual appeal to contemporary artists. Perhaps the greatest strength of the still life is its ability to bring together familiar, domestic objects in unexpected ways to create new formations of art and thought.

The first still life artists in England were Dutch immigrants. Edwaert Collier’s painting in the exhibition, one of many similar pictures by him, features a book, musical instruments, a globe – and a handwritten text, ‘vanitas vanitatum, omnia vanitas’, just in case the slow-on-the-uptake English missed the point. Once English artists start making their own paintings, the still life gets cruder, but also more direct and disturbing. George Smith’s Still life with a joint of beef on a pewter dish includes nothing more than the giant hyper-realist cut of meat and a loaf of bread. Immediately it brings to mind the most visceral paintings of Francis Bacon and Lucien Freud.

The moral, memento mori strain of the Dutch still life runs strongly through the show. Lawrence Gowing, better known now as a critic rather than an artist, has a painting with a skull and mortar and pestle on a table, but rendered in a fractured, double image, a visual echo of the horror felt by the viewer. Mat Collishaw reconstructs, in mock golden age style, the final meal of a US prisoner facing execution (Last meal on death row, Texas (Louis Jones Junior), 2012).

An artist who attached great value to the still life was the death-obsessed Michael Ayrton. His Black still life, ram skull III sets the skull on a table with an egg and a glass vase of flowers, all whitened, against a dark background, except for a vertical shaft of mottled light, like trees seen through the gap in slightly opened curtains. This is what Ayrton had to say about the genre:

The term still life is common enough. At first sight it is a bold, flat designation … yet those two words imply an undercurrent of meaning at once poignant and vital, suggesting objects … curiously related to each other, silent, composed in tranquil, even ominous association. Alive, even lying in wait for the spectator.

Another painting with a black background is Lubaina Himid’s Jug and two spoons. Although this seems, on the face of it, a purely formal work, the longer you look at it the more its features take on that ‘ominous’ look mentioned by Ayrton. The jug and pair of spoons seem disassociated, indifferent or even hostile to each other, against a black background that’s oppressive in its uniformity.

For surrealists the still life was a gift. It was an easy matter to bring together different objects unconnected by rationality in ways that played on the irrational, unconscious mind. Probably too easy: the surrealist works, by Eileen Agar, Edward Bawden and others, form possibly the weakest group of works in the show. Or maybe the English were never really comfortable with surrealism.

But there’s another, apparently quite different, tradition of English still life art. The associations between its objects aren’t moral but entirely formal. The heyday of this strand was in the inter-war period, though it took its lead from the much earlier Cubist paintings by Picasso and Braque. Its leading light was Ben Nicholson. Several works by him in the exhibition show how his still lifes, with their cerebral juxtapositions of shapes and muted colours, led him gradually down the path to full abstraction. There’s a fine 1957 work by an artist unknown to me, Anwar Jalal Shemza. With its music-like geometric shapes, some borrowed from Islamic architecture, its subtle but bold use of colour, and the tactile textures of its paints, Shemza’s painting is something of a blood transfusion after the anaemia of Nicholson’s work.

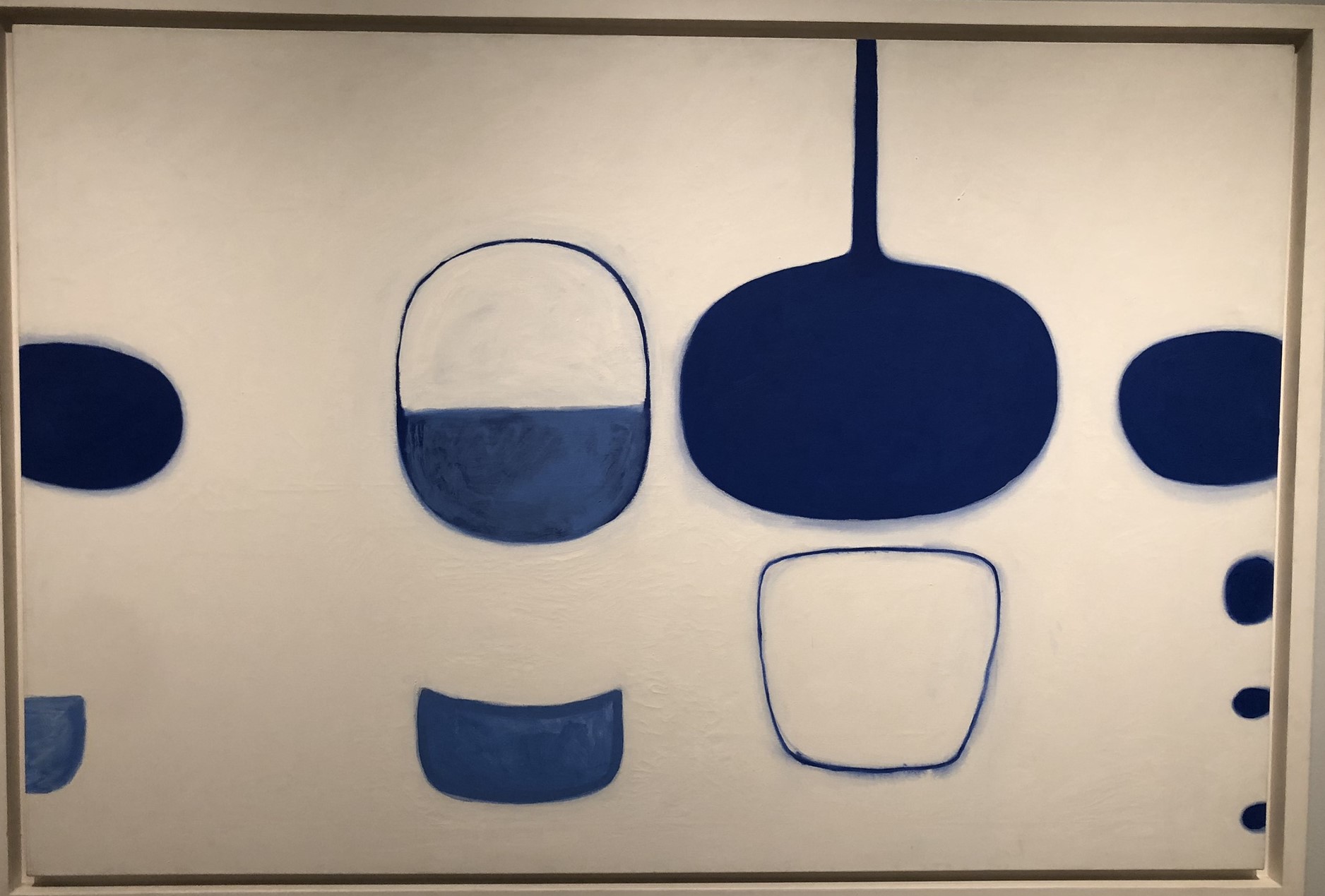

The area where still life meets abstraction is the home of William Scott. In the large painting Still life variations 2 (1969) his blue pans and dishes look as though a road roller has just passed over them: we look at their flat shapes as if from above. Each seems to possess a slight ‘halo’ that saves them from being lifeless, and they’re placed as if in conversation one with another. A smaller but even better painting by Scott is Cup (1974), another (jaunty) conversation between a plain white mug and a precisely rendered blue packet of Gauloises cigarettes.

It doesn’t follow that ‘formal’ still lives are drained of human meaning and expression. This is especially true of flower paintings. Examples in the exhibition transcend the gloomy Dutch moralising, glorying in the evanescence of cut flowers. There’s a wonderful watercolour by David Jones, July change, from the Pallant House collection. Ursula Tyrwhitt is now best known, I’d guess, as a friend and correspondent of Gwen John. But, like both Johns, she went to the Slade School of Fine Art, and was an accomplished painter. Flowers (1912), given as a wedding anniversary present, is a joyous riot of colour, enlivened further by the unusual treatment of the flower stems seen through the water of the transparent jug, and the modernist red zig-zag patterns in the background.

Even better is Winifred Nicholson’s Vermillion and mauve (c1928), another flower painting of great exultation and even greater control, with its brilliantly skilful balancing of colours, shapes and textures. Winifred is still a bit undervalued, despite several recent exhibitions, but give me any of her best works, any time, for dozens of her ex-husband’s.

Vermillion and mauve would be my favourite from the show were it not for the inclusion, right at the start of the exhibition, of a masterpiece, borrowed from a private collection, by Ben Nicholson’s father, William. It’s called The silver casket and red leather box. The circular casket is reproduced with almost photographic accuracy. In its shiny surface can be seen long mullioned windows in the room. Below is the red box, again precisely depicted, in the seventeenth century Dutch style. On it lies a pair of grey formal gloves, which flop down over its front.

It’s a simple, formal composition, but utterly mysterious. Not so much because there’s an untold human story behind the scene (has the owner gone out to the opera, forgetting the gloves?), but because Nicholson poses a more metaphysical question, of the kind the still life genre lends itself to. The question is signalled literally, through the silver clasp of the box. The clasp, together with the catch it would be attached to if it were closed, forms the shape of an inverted question mark in mirror image. Another question is posed by the status of the two receptacles. The lid of the silver casket is presumably locked – at least there’s no sign of a key – but the red box is open. Containment and concealment are clearly one of Nicholson’s themes. There are other mysteries about this painting. The exhibition catalogue mentions that for some reason Nicholson painted the box red only at the last moment, before it went on show in a commercial gallery for the first time in 1920.

William Nicholson’s picture, and indeed the whole exhibition – one of a tiny handful of major still life exhibitions to be staged in the UK in recent decades – show how this apparently humble form of art is capable of firing the imaginations of a surprisingly large number of artists – and viewers.

Leave a Reply