The rose field, published in October, completes Philip Pullman’s massive ‘Book of dust’ trilogy. More than that, it completes the whole cycle of ‘Lyra’ novels that Pullman began thirty years ago with Northern lights. It seems to me that it’s one of the greatest achievements in children’s literature in our time. Though ‘children’s literature’ is a poor label. The children, all those years ago, who read Northern lights – or had it read to them, as happened in our family – may now be reading the last of the novels as adults. That’s not just a chronological point, because Pullman’s writing has become more philosophically complex and difficult over the years.

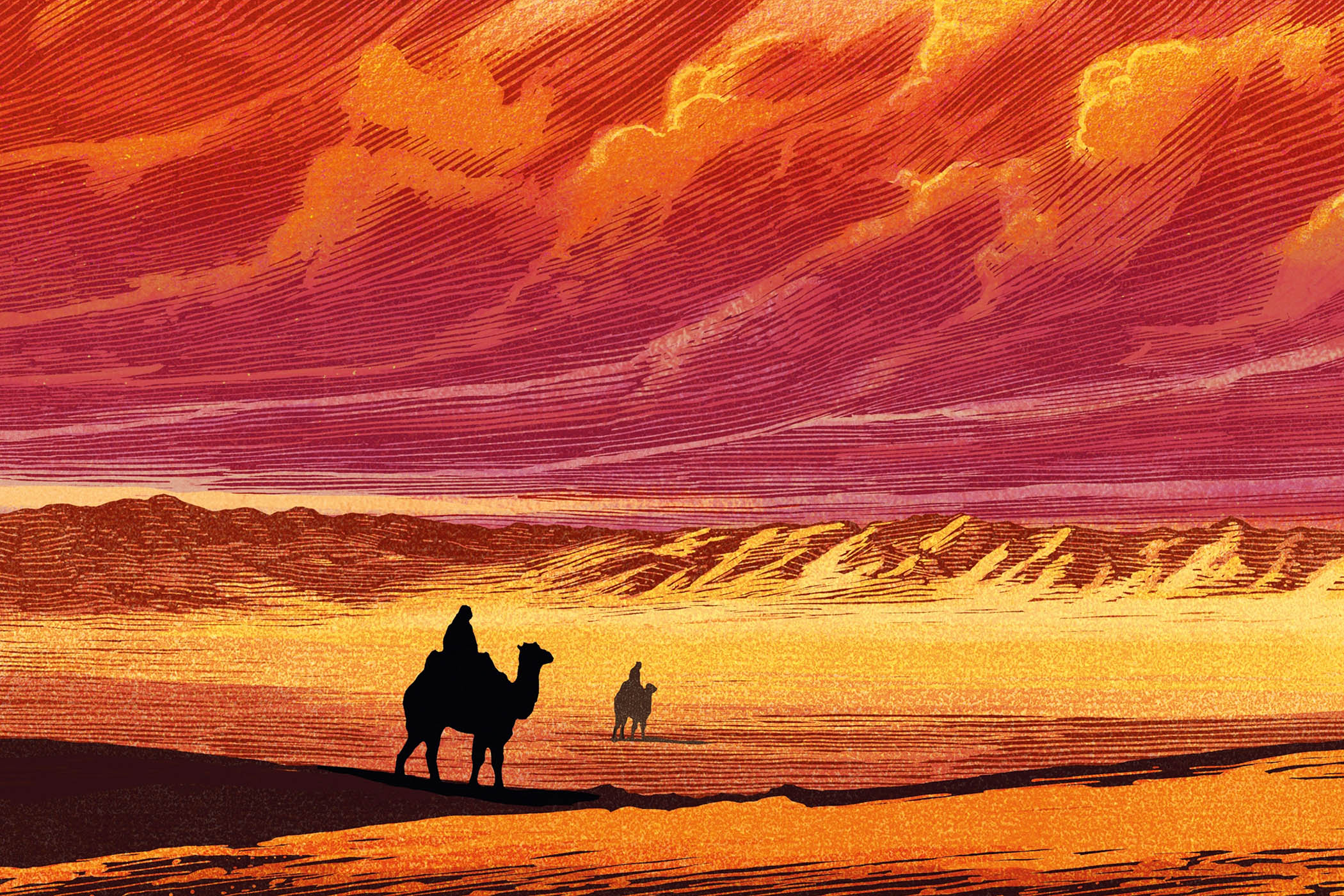

As The rose field begins, Lyra, the cycle’s heroine, is also an adult: Lyra Silvertongue rather than Lyra Belaqua. Pantalaimon, her ‘dæmon’ or non-human alter ego or avatar, now fixed in the form of a pine marten, has deserted her, dismayed by how her mind has been captured by an over-rationalised view of the world and determined to find where her ‘imagination’ has gone to. He’s worked his way east, along the Silk Roads of Pullman’s slightly-alternative world, and Lyra is in pursuit of him. In fact, most of the characters and forces in The rose field are moving eastwards, to converge finally at the ‘red house’ in a lonely place called Karamakan, in the deserts of central Asia. This is one of the main entry points into a parallel universe (one of the constant themes of the Lyra cycle), about which several forces have differing views and intentions.

The rose field is a book of 621 pages, and it ranges over a wide geographical area and also across a huge range of characters and themes. Some readers will judge it as confusing and peripatetic as a nineteenth century Russian novel. The frequent shifting between scenes and people means you need to keep your memory sharp (maybe a cast of characters and certainly a map would have been helpful). In his defence, Pullman could claim that his work is an epic, spanning huge expanses of time, space and ideas.

The villains are as villainous was ever, notably Marcel Delamere, the autocratic President of the High Council of the Magisterium. Other characters, like the international trader and fixer Mustafa Bey and the scientist Abdel Ionides, remain ambiguous and mysterious. As in the previous books, dark and powerful forces are at work: the Magisterium, a kind of ultra-authoritarian Catholic Church, and the wonderfully named Thuringia Potash, an over-mighty international business conglomerate (global turbocapitalism is a relatively new Pullman target). ‘Brytain’ is under the control of a semi-military authoritarian government.

Many of the figures we meet are familiar from earlier books in the series: Malcolm Polstead, Lyra’s rescuer when she was a baby, Glenys Godwin of the dissident intelligence organisation Oakley Street, and Farder Coram, the wise old ‘Gyptian’. Others are new. There are probably too many of them. Fresh figures are still being introduced to us as late as p.576, and others you expect to play a major part are introduced and then never re-enter the stage. And there are new sets of creatures, too: the familiar witches are joined by the fearsome, but rather characterless gryphons (I preferred the armoured bears of Pullman’s Arctic).

At the heart of the book are the subtle boundaries or ‘openings’ between the current world and alternative worlds: thin veils of space that allow passage through them, for those lucky enough to find where they are and how to make holes wide enough to get through. For the Magisterium these other parallel worlds threaten its rigid orthodoxy and totalitarian morality. Delamare plots to find and destroy with explosives the gaps that allow the passage of invasive and challenging ideas. The red house is one of these frontiers: a doorway through which precious and rare rose oil, distilled from rose flowers, was traditionally transported and traded along the Silk Roads. I suspect that Pullman is taking his lead here from T.S. Eliot, in ‘Burnt Norton’, the first of his Four quartets:

Footfalls echo in the memory

Down the passage which we did not take

Towards the door we never opened

Into the rose garden.

Lyra and Malcolm arrive at the red house just in time, and pass through a door into the next world, to the world of the rose fields – only to be disappointed to see that all-powerful developers are grubbing up the rose bushes to make way for expressways, shopping malls and a monetised economy.

Some readers may find the final chapters of the novel deflating or confusing. There are too many abstract and inconclusive conversations about the nature of Dust and the ‘Rusakov’ or ‘rose’ force field. There’s no grand dénouement, and many ends are deliberately left loose. Lyra is reunited with Pan, and, more unexpectedly, with her brother. But their futures are uncertain. ‘What are you going to do?’, Lyra is asked, in the penultimate line of the novel. ‘Go on telling stories, I expect,’ she replies.

Even though no utopias are found, though, we’re not left in any doubt that, despite all the efforts of tyrannical governments (the Magisterium) and brute capitalism (Thuringia Potash), humans, individually and together, have the potential to call into mind, and even into being, different and better worlds. This is the faculty of ‘imagination’. Pullman is known for his hostility to religion, and he’s not referring to afterlives and other fantasies, but to a capacity to defeat oppression, to build a new, more respectful and fairer society here on earth, and to leave some things unsaid and unexplained.

As the novelist Julian Barnes wrote recently (not in any Pullman connection):

… the imagination is dangerous when seen from the other side. It is an alternative power. It can warn us, and it can make us dream. It can picture a better, cleaner, fairer world than the authorities are able or willing to seek. It can conjure up both utopias and dystopias. It can decline the tyranny of religion … A world without imagination would be like living on a dusty planet with nothing but methane to breathe.

Leave a Reply