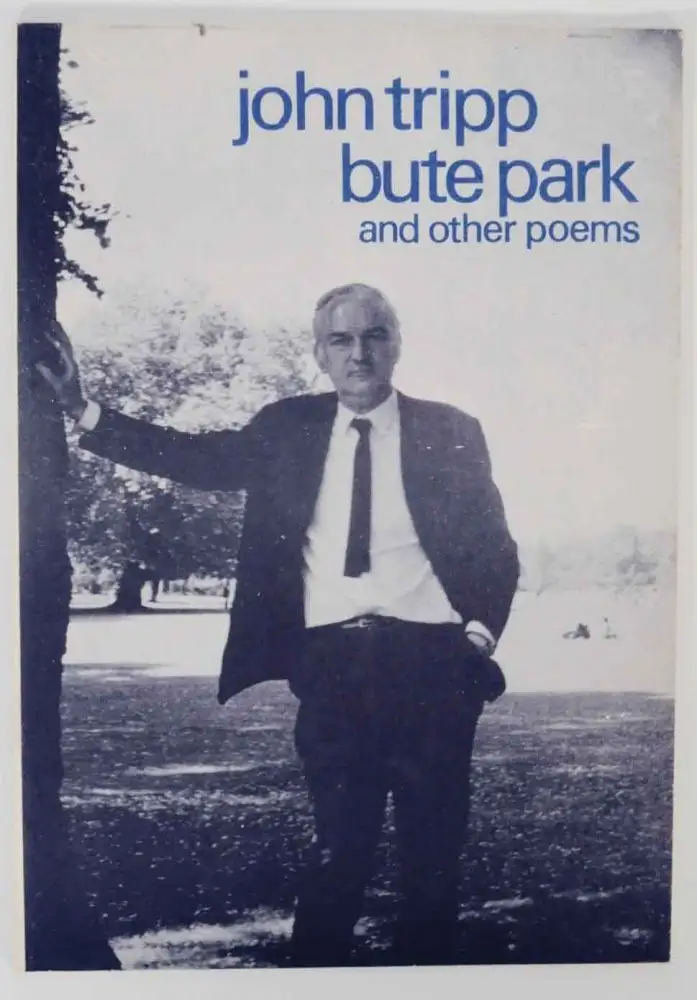

In front of me is a 24-page pamphlet published by ‘second aeon publications’ in 1971. It’s held together with a couple of rusting staples and contains seventeen short poems, typewritten and photocopied. Back then, that’s how you produced a skinny book of poems: gritty, home-made, no upper-case. But this one, John Tripp’s bute park and other poems, is a cut above the ordinary. John Tripp (1927-86), though maybe not much read today, was a formidable and funny poet. And the poems are counterpointed with Barrie Rendell’s black-and-white photos of Tripp, taken in some of the Cardiff locations mentioned in the poems. On the cover, under the slightly wonky title, the pugnacious, hard-drinking poet makes a stand, one hand leaning on a Bute Park tree trunk, the other deep in his trouser pocket.

Poem 7, ‘Upstairs at the Griffin’ takes us to a pub poetry reading:

You climb to the action

by way of a bar, convenient

for trays of ale. The stairs go

to a shattered room – the kind of room

Lenin’s cabal used to meet in.

An untuned guitar swamps a voice

that is flat but sincere, somebody knocks a bucket

coming back from the bogs.

A machine-gun of verse spits at us

to block any yawns,

a fast switch of poets

narrating their own things

It all goes under the ballpoint –

the mad geography of our lives.

This world of small press publishing, pubs and poetry reading was the world of the young Peter Finch. ‘second aeon’ was his own press and he was already, by the early 1970s, a dynamic force in what he calls, in the title of his latest book, published by Parthian, The literary business.

I can think of more exciting titles for a book about on-edge poetry and off-beat poets. But in fact ‘literary business’, in the commercial and the organisational senses, describes pretty accurately the story Peter has to tell. It’s the story of his life as a poet and as a literary animateur – advocate, champion, organiser, bookseller, campaigner, hustler, promoter, diplomat. He tells the story in a lengthy series of short essays or ‘film-clips’. The pieces were written at different times, and there’s some repetition, but together they amount to a picture of a fast-paced public life of astonishing achievement.

The book has the feel of a ‘closing of accounts’, following on from the 2022 publication in two volumes of Peter’s Collected poems. It’s not an irrelevant metaphor, because, until the literary business took over, he earned a living as a local government accountant. Lenin (The state and revolution, ch.3) maintained that every revolution needed its ‘foremen and accountants’: radical fervour and arms were not enough to create the socialist society he sought. In the same way, Peter’s organisational skills set him apart from most of the anarchic poets and other writers he admired and supported, and allowed him to transform creative enthusiasm into concrete results (as well as concrete poems).

The list of Peter’s achievements is long. His ‘second aeon’ produced not only individual pamphlets but also a poetry periodical of the same name. It began in 1966 and grew to be highly influential in the new poetry scene, well beyond Wales. He was able to attract to Cardiff poets from elsewhere in the UK, the US and Europe, to speak in readings and conferences and publish with him. Many, though not all, belonged to the experimental (concrete, sound and visual) wings of poetry. Among them were Bob Cobbing, George Macbeth, Chris Torrance, and Brian Patten. He published and read his own poems in increasing numbers. By 1973 he was manager of Oriel, the Arts Council’s bookshop-cum-gallery in Charles Street, and continued to run it after it moved elsewhere. After that, he became head of Academi, part literature-developer, part writers’ trade union. There he had a hand in dozens of developments, including commissioning Gwyneth Lewis’s inscribed words on the Wales Millennium Centre, inaugurating the post of National Poet of Wales, and beginning the Wales Book of the Year competition. And on top of all that, he’s continued to publish his own work – not only poetry but a whole series of books on places, the blues and poetry-writing and publishing – and he’s edited the work of others (notably the ‘Real …’ series).

For me, when I lived in Cardiff in the 1970s and 1980s, his greatest invention was Oriel. Oriel stood like a cultural lighthouse towards the bottom of Charles Street, its block-like building pushing its stripy face boldly into the street. On Saturdays I’d often wander down there and, after a glance at the current art exhibition on the ground floor, lose myself upstairs among the shelves-full of poetry books, local books, art books and much else. ‘Oriel’ was an inspired, bilingual choice of name, because it had a gallery, but it also threw open a wide window on to literary culture. Readings and other events were common. Oriel was where I first heard R.S. Thomas, grave and severe, reading his work. (The second time was when I listened to a Sunday sermon in St Hywyn’s Church, Aberdaron, when he bemused the congregation with a summary of Plato’s Theory of Forms.)

Many figures crop up again and again in The literary business. Near the top of the list is Meic Stephens, the legendary head of literature at the Welsh Arts Council (and political activist, poet and editor). In many ways Peter was Meic’s heir as Wales’s ‘literary animateur’, and certainly his equal in his energy and ability to make things happen. (I hadn’t known before that Oriel was the sole result of a quixotic and doomed attempt by Meic Stephens to set up a network of state bookshops throughout Wales.)

One of the other heroes of the book is Cardiff, where Peter was born and where he’s lived all his life. In recent years, thanks to its Council’s subservience to big business and its neglect of conservation, the city has lost much of what made it distinctive, and the book has an elegiac tone when it recalls the pubs, clubs and other bohemian haunts that have vanished. Peter stands in Charles Street and laments its transformation from what was once a messy mix of bohemia, religion and small business, into the backsides of chain shops and soulless student flats.

But elegy isn’t the dominant key. Peter is too busy bringing back to life his creative eccentrics (there are concise portraits of Cyril Hodges, George Dowden, John Tripp, Bob Cobbing and Nigel Jenkins), the grubby dives where poets read, the hand-to-mouth economics of poetry publishing, and attempts to limit bookshop ‘shrinkage’. And it’s a book full of self-deprecating humour and good jokes. My favourite story of his (not, I think, in the book) is about ambushing the legendary blues musician Willie Dixon at the stage door after a gig and asking him to read his own blues lyrics from southside Cardiff (‘Got the blues in Roath Park this mornin’).

There are other reasons to read The literary business. Five sections labelled ‘How the poems arrive’ distil years of experience of coaxing poems into being. There’s advice on how to publish your poems, how to launch your slim volume, and how to arrange a poetry event (and how not to). And there’s a generous sprinkling of Peter’s own poems, some of them, to his surprise, now on school curricula.

The book’s cover carries three photos of Peter Finch. They look nothing like one another. Could there be several Peter Finches? That could explain how he’s managed to pack so much in to a single literary life, to the benefit of so many people – and to stay so positive and optimistic. At the Mumbles launch of the book, I asked him what he thought of literary culture in Wales today, compared with that of the 1970s and 1980s. Without hesitation or any reference to the decline in public support for the arts or any other current problems, he replied that today’s scene was livelier by far.

Leave a Reply