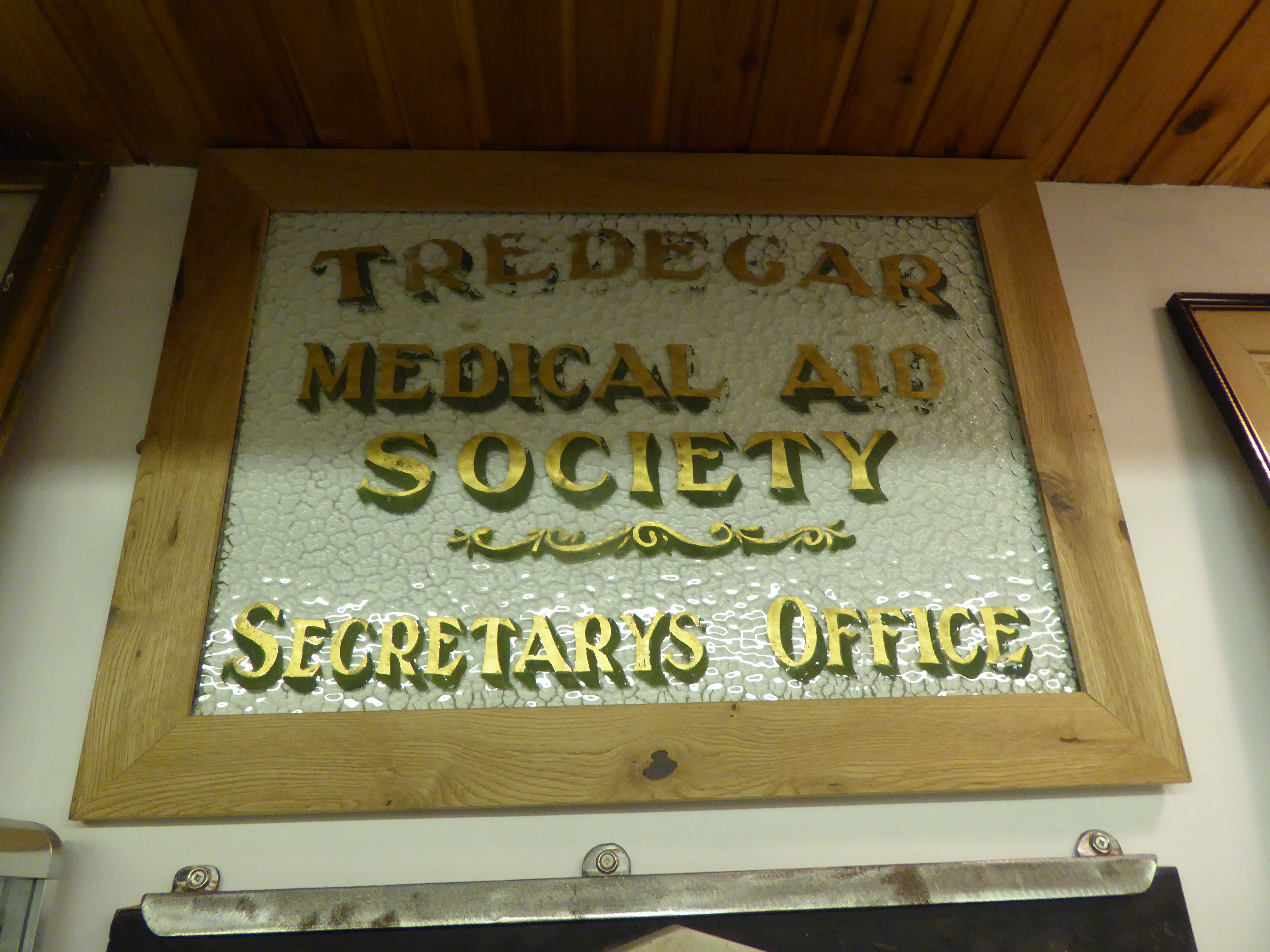

In the last couple of weeks I’ve been in and around Tredegar – Tredegar as it is today, but mostly Tredegar as it was in the first part of the twentieth century. Most people know about the town’s best known resident, Aneurin Bevan, and many know about Bevan’s pre-War experience of the pioneering services run by the Tredegar Workmen’s Medical Aid Society – often claimed to be a forerunner of the NHS. It doesn’t take much rummaging in the history of the Medical Aid Society before you come across the commanding figure of its Secretary, Walter Conway.

Conway was born in Tredegar in 1873. He didn’t enjoy a privileged childhood, to say the least. Orphaned when very young, he was sent to live in Bedwellty Workhouse. There, he said, he learned independence and a love of books. He was probably an avid user of the well-stocked library in the Tredegar Workmens’ Institute, as well as a student in evening classes. In his teens he became a coalminer and quickly became politicised, joining the Independent Labour Party, though there was no ILP branch in the town until 1911. In 1909 he was elected to the Bedwellty Board of Guardians.

In 1915 Conway was appointed as Secretary to the Tredegar Medical Aid Society. The Society had begun in the 1870s as a contributory ‘Health and Education Fund’, but the educational function had been abandoned, and the Society concentrated on providing miners and their families with medical provision. Members contributed a fixed proportion of their earnings (1¾d in the pound at the start) into the scheme. When they fell ill or were injured they could see a doctor or nurse, or go to hospital, without payment.

By the time Conway became its Secretary the Society had already built a Cottage Hospital (in 1904), added a women’s and children’s ward (1907) and a new wing (1914). The building still stands, though it’s been empty and boarded up since 2010, and there’s been talk recently of demolition. By the time the First World War was over the coalfield’s boom was at an end. For most of the 1920s and 1930s the miners were on the defensive, as pits closed, wages were cut and unemployment took hold. The depression placed the Medical Aid Society in difficulty, as contributions were fewer but medical needs did not decline. Walter Conway, though, seems to have steered the Society with great skill through these hard years, answerable as he was to a Committee (the Hospital was governed by a separate one). Both committees had company nominees as members, though the worker members were democratically elected. By the time he died, the Tredegar scheme was held to be the most comprehensive one of its kind in Wales. Already in the 1920s the Society employed five doctors, a surgeon, two pharmacists, a physiotherapist, a dentist and a district nurse. By the 1940s almost everyone living in the town was covered by its services.

In Tredegar Walter Conway was known as a radical socialist. He had a strong intellectual and political influence. During the First World War he argued fiercely against the domination of food control and other committees in the town by the middle classes, and spoke in favour of the workers representing themselves, rather than relying on the Company’s philanthropy or the Liberal Party’s sympathy. Conway spoke about food control in a meeting of the Tredegar Trades and Labour Council in December 1917 and was strongly supported by Aneurin Bevan – this was Bevan’s first ever reported speech. As Susan Demont has shown, it was during the War that the Tredegar labour movement, previously weak, began to win serious political support among the miners.

Conway was a leading member of the radical Query Club, formed in 1920. The Club was a cross between a debating society, a mutual support fund and a political caucus intent on wresting control of Tredegar’s institutions, including the Medical Aid Society, away from the influence of the town’s main employer, the Tredegar Iron and Coal Company and into the control of the workers. Michael Foot, in his biography of Aneurin Bevan, suggests that Bevan was the founder and inspiration of the Club, but a surviving photograph shows Conway sitting in the middle of the group, and he may also have been the Club’s intellectual focus. He acted as a personal mentor to Bevan, who was 24 years younger than him. It was he who showed Bevan how to overcome his severe stammer. Conway’s advice, on the basis that ‘if you can’t say it, you don’t know it’, was to read and prepare thoroughly before beginning any speech. Conway had been a tutor in Central Labour College classes in the town from 1916 or 1917. Bevan attended them, and it’s very possible that he was encouraged by Conway to attend the Central Labour College in London, where Bevan gained his main political and economic education between 1919 and 1921.

Walter Conway, everyone seems to have agreed, was a person of understanding, warmth and generosity. In the museum in Tredegar one of the volunteers was keen that I should see the stone erected by students of his Sunday School class after his death aged 58 in February 1933. ‘Greatly beloved’ is the epithet on the memorial: ‘he followed in the footsteps of the master’.

In his popular novel The Citadel, published in 1937, A.J. Cronin paints a brief picture of Conway. Cronin had been employed as a doctor by the Tredegar Medical Aid Society between 1921 and 1924 and knew its Secretary well. Conway’s character, ‘Owen’, is one of the few in the novel to escape criticism or condemnation (Cronin was no lover of how medicine was organised in his time and he found working in Tredegar a frustrating experience). The book’s hero and Cronin’s alter ego, Andrew Manson, arrives for his interview. ‘At the small side-table was a pale, quiet man with a sensitive face who looked, from his blue pitted features, as if he had once been a miner. He was Owen, the secretary.’ Later on, Owen confides in Manson: ‘In his quiet voice he began to tell them about his own early struggles, of how he had worked underground as a boy of fourteen, attended night school and gradually ‘improved himself’, learning typing and shorthand, and finally securing the Secretaryship of the Society. Andrew could see that Owen’s whole life was dedicated to improving the lot of the men. He loved his work in the Society, because it was an expression of his ideal. But he wanted more than mere medical services. He wanted better housing, better sanitation, better and safer conditions, not only for the miners, but for their dependants.’

In his popular novel The Citadel, published in 1937, A.J. Cronin paints a brief picture of Conway. Cronin had been employed as a doctor by the Tredegar Medical Aid Society between 1921 and 1924 and knew its Secretary well. Conway’s character, ‘Owen’, is one of the few in the novel to escape criticism or condemnation (Cronin was no lover of how medicine was organised in his time and he found working in Tredegar a frustrating experience). The book’s hero and Cronin’s alter ego, Andrew Manson, arrives for his interview. ‘At the small side-table was a pale, quiet man with a sensitive face who looked, from his blue pitted features, as if he had once been a miner. He was Owen, the secretary.’ Later on, Owen confides in Manson: ‘In his quiet voice he began to tell them about his own early struggles, of how he had worked underground as a boy of fourteen, attended night school and gradually ‘improved himself’, learning typing and shorthand, and finally securing the Secretaryship of the Society. Andrew could see that Owen’s whole life was dedicated to improving the lot of the men. He loved his work in the Society, because it was an expression of his ideal. But he wanted more than mere medical services. He wanted better housing, better sanitation, better and safer conditions, not only for the miners, but for their dependants.’

The rich labour history of Tredegar is well remembered today, even if the museum deserves some investment and the archives still more. It’s impossible to walk the streets without being reminded, by statues, gates, inscriptions and roundels, of Aneurin Bevan and his greatest achievement, the National Health Service. The Tredegar Medical Aid Society too is commemorated, and its greatest Secretary. There’s a Walter Conway Avenue in Cefn Golau. And on the pavement outside the dilapidated old Town Hall is a handsome stainless steel bench, erected in 2013. It was designed by Tim Ward, one a series of twenty silhouette figures from Tredegar’s past that together define the Homfray Trail. Two figures are welded into the bench, Aneurin Bevan standing on the left and Walter Conway sitting on the right. The two of them look across, past the clock tower, towards the offices of the Medical Aid Society at no. 10, The Circle, where Conway cared for the health of his people for nearly twenty years.

The rich labour history of Tredegar is well remembered today, even if the museum deserves some investment and the archives still more. It’s impossible to walk the streets without being reminded, by statues, gates, inscriptions and roundels, of Aneurin Bevan and his greatest achievement, the National Health Service. The Tredegar Medical Aid Society too is commemorated, and its greatest Secretary. There’s a Walter Conway Avenue in Cefn Golau. And on the pavement outside the dilapidated old Town Hall is a handsome stainless steel bench, erected in 2013. It was designed by Tim Ward, one a series of twenty silhouette figures from Tredegar’s past that together define the Homfray Trail. Two figures are welded into the bench, Aneurin Bevan standing on the left and Walter Conway sitting on the right. The two of them look across, past the clock tower, towards the offices of the Medical Aid Society at no. 10, The Circle, where Conway cared for the health of his people for nearly twenty years.

If the two of them could come back to life and take a walk round the town, I fear they might feel dismayed. Forty years of neo-liberalism have not been kind to Tredegar. More than half the shops are boarded up. Many older public buildings are derelict. There were few younger people to be seen. In the paper shop, I interrupted a conversation about the proposed car racing track at Ebbw Vale, the Circuit of Wales, which has just been denied financial support by the Welsh Government. The shop’s owner felt that this was no loss: little economic benefit, she thought, would have flowed to local people. I couldn’t help agreeing. If the Welsh Government wants to help Tredegar and its area it should be able to think of better ways of restoring the town and its economy. Restoring the NHS to what a reborn Bevan might find acceptable is a rather larger, but just as urgent, matter – for us all.

Leave a Reply to Andrew Green Cancel reply