Paintings, not painters, you’ll notice. And the artists are all safely dead (this avoids treading on the toes of the living). Third, I wouldn’t claim that these are the best ten paintings. They’re just works that have given me special pleasure and contemplation. Many aren’t very well known.

But see what you think about my choices – they’re arranged in chronological order – and do nominate your own selections.

Thomas Jones, Ruined buildings, Naples (1782) (Glynn Vivian Art Gallery, Swansea)

I love the fact that I can get on my bike, cycle along the prom and call in at the Glynn Viv to see this painting, for free and at any time (well, whenever the Glynn Viv’s open). It’s usually on display, and for good reason, because it belongs to that group of small, miraculous pictures of buildings Thomas Jones Pencerrig painted from, or near to, his apartment in Naples in 1782.

I also love that fact that no one’s ever succeeded in explaining why he painted them. He didn’t intend to sell them to Grand Tourists. They’re not sketches for later works. In fact, they’re not sketches at all, but very carefully thought out and executed oils – and in a style other artists wouldn’t arrive at for decades, if not centuries.

The third thing I love is that Thomas Jones was such a genial and jolly person, as you sense from his memoirs and from Francesco Renaldi’s family portrait. A friend described him as ‘a little stunted man, round as a ball, the truest Welsh runt’.

John Sell Cotman, Cadair Idris, [1830s] (British Museum)

Before his golden period in Yorkshire and Durham in 1803-05, when he painted the astonishing proto-modernist watercolours for which he’s best known, Cotman made two trips to Wales, in 1800 and 1802. He used the sketches he made then as the basis for paintings when he returned home. But his vision of the mountains of the north stayed lodged in his mind for many years afterwards, and in the 1830s he made a series of small, highly experimental paintings of Cadair Idris. He added paste (flour or rice) to his watercolour to give the paint more body, and his predominant colour was a deep, resonant blue.

Sydney Kitson, Cotman’s biographer, used the word ‘celestial’ to describe these works – not a hyperbole when you’re sitting before them and marvelling at how Cotman, with the inner eye of memory, was able to crystallise the wild sublimity of the mountain.

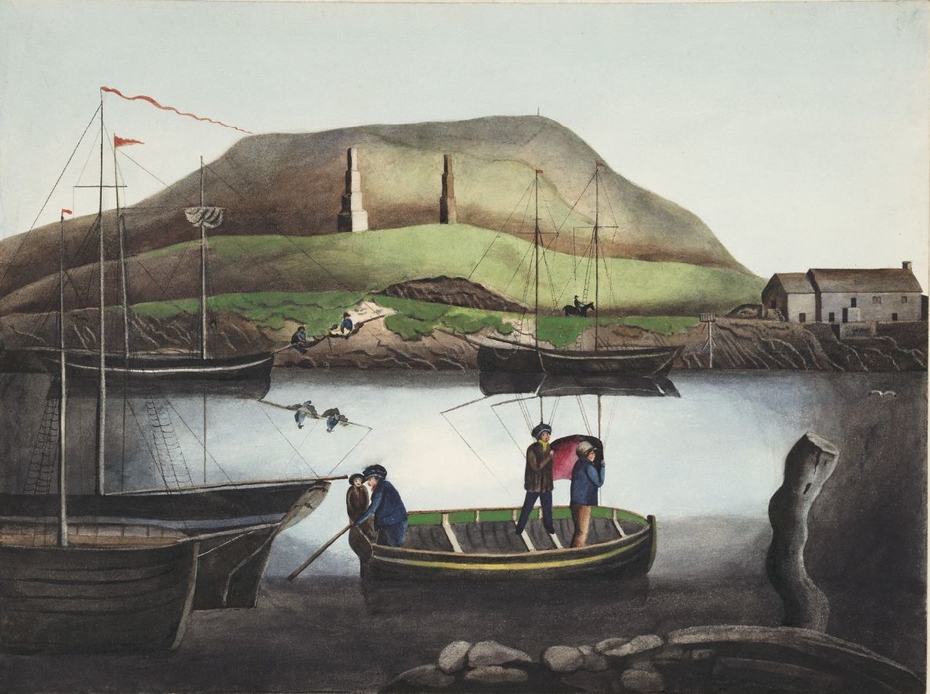

Anonymous, Aberystwyth harbour (c1840) (National Library of Wales)

As a former resident at the mouth of the Rheidol I’ve always liked the views of the area by an anonymous artist once known, quite wrongly, as ‘The Welsh Primitive’. He or she, who seems to have lived in or around Aberystwyth around 1840, maybe not have received conventional art training, but had a natural eye for composition, for colour and especially for tone (look at the modulations in the lake-like surface of the river).

Nothing much is happening here – the men and boys in the boast are barely exerting themselves – and a gentle lyricism suffuses the painting. Pen Dinas rises, plump and comfortable, in the background. Most of this artist’s pictures share a poetic quality, and some, like ‘Moon rising above Plynlimmon’, have an otherworldly dreaminess. It would be good to see all of the fifty or so paintings, split between the National Library and Carmarthenshire Museums, reproduced faithfully in book form.

James Lewis Walters, The Llanboidy molecatcher [c1900] (Carmarthenshire Museums, Abergwili)

When I saw this oil painting for the first time in Carmarthenshire Museum, I stood in front of it for quite a while, amazed at the theme and the execution. Little is known about James Lewis Walters. He was born in Looe, Cornwall, the son of a sea captain, but by 1891 he was living in Llanboidy, with his Welsh wife Elizabeth, and making a living as a chemist, and wine and mineral water merchant. How he learned the skills of a painter is unknown, but it’s clear from this work and others that he was an accomplished artist.

This is a double portrait. The man setting the mole trap is William Thomas or ‘Wil Boy’, a local character. The other, a working man from Llanboidy called Robert Lewis, doffs his cap and offers his pipe to Wil. The painting belongs to a ‘meeting’ or ‘greeting’ genre, of which ‘Bonjour Monsieur Courbet’ by Gustave Courbet is the best-known example. It’s a large canvas, and Walters, who was clearly familiar with the French realist tradition, lavished great care on the details, especially the dress of the two figures and the bucolic east Carmarthenshire landscape in the background. His painting, quietly monumental, celebrates the lives of two ordinary people and their labour.

Charles William Mansel Lewis, In the golden weather (1905) (Carmarthenshire Museums, Parc Howard, Llanelli)

Here’s another large painting that makes an immediate impact on the eye when you stand in front of it in Parc Howard. In the golden weather freezes a single moment: a moment in autumn just as leaves are beginning to fall on to the small lake at Stradey. Some already float on the water, but for the time being everything is still, as the slanting sun lights the trees, throwing golden shadows on the still lake. Soon the wind will rise, the wood will be in trouble, and leaves will rain heavily on the water. The painter’s treatment of the scene combines realism and impressionism to create a wonderfully harmonious whole, paradisal or melancholic, according to your mood.

Mansel Lewis, who led a privileged life as the owner of Stradey Castle, developed a strong interest in painting. He became a friend of the German painter Hubert Herkomer and the two would go on painting holidays together. The pictures that resulted from these trips, along with his other, more local landscapes, are worth seeking out.

Brenda Chamberlain, The doves (1953) (Storiel, Bangor)

For years I’ve been trying to get to Ynys Enlli. But each time the weather’s been too poor to make the crossing from Aberdaron. The island now has the mythic status of an unattainable goal. But of course many people do go there, and some, like Brenda Chamberlain, have lived there.

She was first taken in 1946. ‘After two days of running wild on Enlli’, she explained years later, ‘it was the only place for me to live’. She went back, and stayed for fourteen years, the most creative period of her artistic life. She used the islanders and their children as her models in her paintings, which took their cue from French modernism. Life on the island was turbulent, as is clear from Chamberlain’s novel-memoir Tide-race – she was poet and novelist as well as painter – but her pictures speak of harmony and tranquillity. As a painter of children her only equal in Wales is Claudia Williams.

Esther Grainger, Pontypridd at night (1953) (National Library of Wales)

At first sight this looks like an abstract painting. Then your eye adjusts to the nocturnal setting and the bird’s eye viewpoint, so that the town begins to take shape, huddled beneath its hills and the star-like streetlamps. Chapels and house terraces intertwine at the bottom of the winding path, while a fiery bush explodes in the foreground. It’s a bold painting, roughly done, on board rather than canvas, and I’ve loved it ever since I first saw it in the National Library.

None of Esther Grainger’s other paintings – at least the few in public collections – are as radical as this one, though ‘Sunflower tops’ in Cyfarthfa Castle is a lovely, summery picture. During her lifetime Grainger was better known as a teacher and organiser associated with the ‘settlement’ at Pontypridd during the Depression. Her art seems to have received less attention than that of her contemporaries, and you suspect that as a woman she may have held back by prejudice and condescension.

Jack Crabtree, The day before the ballot (1974 or later) (National Library of Wales)

Industrial paintings are important in the art of Wales, and they don’t come better than those of Jack Crabtree. In 1974-5 he was commissioned by the National Coal Board to make an artistic record of south Wales miners at work. The result was a series of outstanding pictures: landscapes, portraits and group scenes, like this one, alive with the bustle and excitement of the holding of a strike ballot. Alas, the collection was scattered, and only some of the original series can be found now in public collections.

The preparatory drawings Crabtree made are, if anything, even more impressive than the finished paintings. Taken together, the works are a vivid document of a community and culture that had developed over a century, but had only another ten years to live.

Ron Lawrence, The rugby match (1984) (National Library of Wales)

For years I had the great privilege of being able to look at Ron Lawrence’s picture of Sardis Road every day from my desk in the National Library. It always seemed to me to encapsulate some of the social essences of the Welsh experience. I don’t mean just the rugby – Pontypridd are playing, and you assume, beating Cardiff – but the way in which the ground, the terraced streets around, and the hills beyond all seem to form enfolding concentric circles – a metaphor, maybe, for the ‘agosatrwydd’ and communitarian tradition of Wales.

Your eye’s drawn to the off-pitch figures: the children scrambling up the wall to see the match without paying, the women chatting in a back garden, the boys ignoring the rugby and engrossed in playing football. It’s a bright, human, happy painting.

Roger Cecil, Untitled I (c2000) (MOMA, Machynlleth)

When Roger Cecil died in 2015 only a few people were aware of the greatness of his art. Posthumous exhibitions and Peter Wakelin’s generously illustrated portrait, Roger Cecil: a secret artist have begun to change that. I met Roger only once, in 2011, in his home in Abertillery. It was an encounter I’ll never forget, and it sent me back to discover how his art had developed over fifty years.

MOMA has one of his largest and most powerful later works, Untititled I. Like many of his paintings, it hides in its abstraction signs of the real, local features – paths, walls and other marks – of his beloved valley (he’d turned his back on a course at the RCA in London to return home in 1964). When you look at the picture in the flesh it’s impossible not to be overwhelmed by the colours, especially the rust red, and the sculptural surface, many times worked, of the board it’s painted on.

Leave a Reply to Andrew Green Cancel reply