The sandsone ridge of Cefn Bryn is an obvious magnet for painters, but it doesn’t seem to have drawn many creative writers, despite its brooding presence along the backbone of the Gower peninsula. One exception is Amy Dillwyn, the pioneering industrialist, feminist and lesbian, in her best-known work The Rebecca rioter (1880), an historical novel based on the Rebecca riots of 1839-43..

Dillwyn, never a conformist, takes the side of her ‘rioter’, Evan Williams, a young labourer from Killay, Swansea. She follows his adventures as a convert to the rioters’ cause, his part in the rioting and killing of a magistrate, and his flight from justice, from Swansea, across Gower, at sea on the Bristol Channel and back to Swansea, where he is imprisoned and transported to Tasmania.

In his escape Evan first hides with his friend Tom in Clyne Woods, intending to take a boat from Mumbles, but he spots policemen on Clyne Common and decides instead to make for Oxwich by an inland and upland route:

As soon as it was night we left our hiding – place and crossed Fairwood by Carter’s Ford and reached a farm named Killibion [Cillibion], which is on the north side of the hill called Cefn Bryn; as Oxwich Bay is two or three miles on the south side of this hill, we had now only to cross the long ridge and descend into the bay, where we hoped to find a vessel. But the darkness was now changing to daylight, and so we took possession of an old shed that we found near Killibion in which we rested safely during the day, making sure that we should easily get down to Oxwich in the course of the next night …

But mist is worse than cloud or rain, and by the time were halfway up Cefn Bryn a thick mist came on in which it was we impossible to see a yard before one, and which completely puzzled us. On we went, however, with nothing to guide us except the knowledge that we ought to keep going up hill continually until we should get to the top. But the hillside was covered with great pieces of rock, which often made it difficult to know with any certainty know with any certainty whether we were going up hill or down. Streams and small bogs abounded also, and we remembered having been told that on Cefn Bryn were one or two deep bogs which anyone who got into would have a difficulty in getting out of again. We heard the water gurgling and bubbling around us, and felt the soft ground shake and quake under our footsteps when we passed over the wettest parts; but whereabouts we were we had no idea as we floundered and struggled on at random in the intense darkness.

All of a sudden, Tom, who was close to me though I could not see him, called out; and at the same moment there was a great splash. ‘What is it, Tom?’ cried I. But no answer did I have, nor did I hear any further sound. I stretched out my arms to try and feel him, but in vain. Then it struck me that he must have fallen into one of the small deep pools that are often to be found in boggy places. I was horrified at the thought, for I knew he could not swim a stroke …

Evan manages to rescue Tom from drowning, just as he’s about to disappear for the last time. They despair of crossing the hill at night in the mist, and they wait, hungry and soaking wet, till morning. When the mist clears they realise there’s no hiding place for them on Cefn Bryn. Still hoping to escape by boat from Oxwich, they decide to make their way down to shelter in the old castle at Penrice, on the south side of the ridge.

A few years ago Evan’s flight through Gower was tracked by the AHRC-funded project Literary atlas: plotting English-language novels in Wales. The researchers explored the various significances of place in novels of various periods set in specific geographical settings throughout Wales. The Rebecca rioter, with its highly detailed itineraries through places intimately known by its author, was an obvious candidate for inclusion. Map-plotting the route taken by Evan and Tom is relatively easy. And yet a novel is a novel, not a footpath guide, and the Cefn Bryn episode is a good example of how a creative writer can elasticate geography to suit her narrative needs.

Amy Dillwyn deliberately exaggerates the difficulty of scaling Cefn Bryn, and sets lethal traps where none exist. In reality, walking up the hill from the north is not much more than a short and gentle stroll. There are some stones, but no ‘great pieces of rock’ to be tackled. In wet weather you certainly need boots, and although there are some boggy ponds here and there it would be a very unlucky person, of very short stature, who could possibly be in danger of drowning. Even travelling in the dark and in mist and rain, you would be crazy to spend the night on the hillside, as Evan and Tom do, rather than crossing Cefn Bryn to the south side.

But these naturalistic objections are beside the point. Amy Dillwyn isn’t confined by the real-life geography of Gower: she’s interested in increasing her narrative tension by heaping as many hazards and troubles in the path of her refugees as she can. If in the process Cefn Bryn grows in stature to resemble Pen-y-fan or Tryfan, so much the better. Robert Louis Stevenson uses similar techniques in his own account of rebels on the run, the flight of Alan Breck Stewart and David Balfour through the heather in Kidnapped, first published six years after The Rebecca rioter.

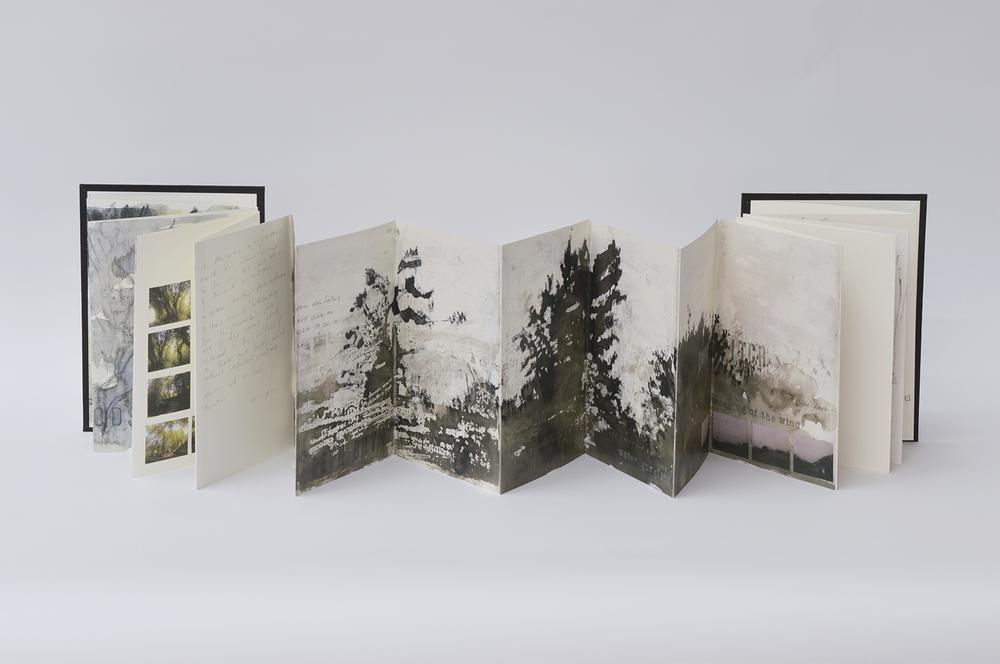

As one of the offshoots of its work the Literary atlas project commissioned visual artists to make new works inspired by the twelve chosen novels. As her contribution to the resulting exhibition, Valerie Coffin Price created an artist’s book, a ‘folding sketchbook’ containing images from ‘a rioter’s walk’. She followed the walking route of the fleeing pair, and used drawing, paint, lettering and photographs to make a kind of still movie of their physical and internal journey through the landscape.

Polly Oliver has a short poem named Cefn Bryn but I’m not aware of many other literary reflections of Cefn Bryn. Maybe you can help?

Leave a Reply