Book 6 of Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy contains an insight that few, if any, novels – or indeed any works of non-fiction – published before or since, have achieved.

In chapter 39, a message reaches the house of Tristram’s parents that Uncle Toby, his father’s brother, a veteran injured in the groin in the siege of Namur, is at last expected to marry the Widow Wadman, after a long courtship.

I have an article of news to tell you, Mr. Shandy, quoth my mother, which will surprise you greatly.——

Now my father was then holding one of his second beds of justice, and was musing within himself about the hardships of matrimony, as my mother broke silence.———

“——My brother Toby, quoth she, is going to be married to Mrs. Wadman.”

——Then he will never, quoth my father, be able to lie diagonally in his bed again as long as he lives.

When you first come across it, the idea that sharing your bed with another human, whether in marriage or in any other lengthy relationship, might put an irreversible end to your freedom to arrange your limbs in the bed exactly as you please – and especially in a crosswise way – is one that strikes with some force.

As so often, it’s taken several centuries for people to catch up with the full implications of Sterne’s innovative thought. Even today, the world’s mightiest search engine finds it difficult to unearth anything much on this critical topic. So it’s hard to reach any firm conclusion on the truth of Walter Shandy’s observation, unsupported by any evidence except, presumably that of his own sleeping experiences with ‘my mother’.

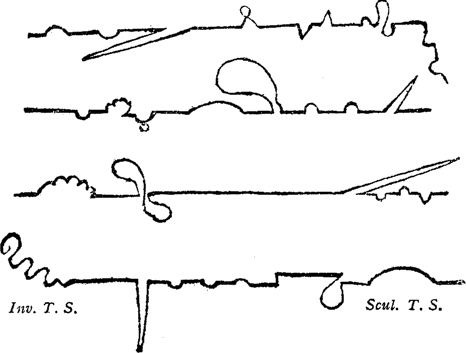

Of course, for Sterne ‘diagonal sleeping’ has a more resonant meaning than its immediate bedroom setting suggests. It’s an unconventional metaphor for something very dear to him: the principle of the random, free, anarchic, quirky and uncontrolled. Tristram Shandy is a hymn, written in an age when the Enlightenment was promoting the supremacy of the rational, to everything that was not rational: accident and misfortune invariably undermine and mock the best efforts of Walter and other believers in a comprehensible universe or the reasonable planning of human affairs. The same is true of Tristram’s own narrative. It almost never moves forward in a straightforward way, but by way of digressions and every form of backward and forward movement – as described, in the very next chapter after ‘diagonal sleeping’, in his graphical representation of the narrative course of volumes 1-4.

‘Diagonal’ makes another appearance, as a marker of free, unorthodox behaviour, in Book 2, chapter 9, when Doctor Slop, the male midwife, riding fast on his pony up to Shandy Hall, almost collides with Odadiah’s coach horse coming in the other direction:

So that without waiting for Obadiah’s onset, he left his pony to its destiny, tumbling off it diagonally, something in the stile and manner of a pack of wool, and without any other consequence from the fall, save that of being left (as it would have been) with the broadest part of him sunk about twelve inches deep in the mire.

Elsewhere the ‘diagonal on the bed’ theme is capable of affective as well as comic force. In Book 3, chapter 29, Walter, having heard the news that Dr Slop, in delivering the baby Tristram, has ‘crush’d his nose, as flat as a pancake to his face’, retires to his bedroom in despair, convinced that pain and sorrow are best tolerated ‘in a horizontal position’:

The moment my father got up into his chamber, he threw himself prostrate across the bed in the wildest disorder imaginable, but at the same time, in the most lamentable attitude of a man borne down with sorrows, that ever the eye of pity dropp’d a tear for.——The palm of his right hand, as he fell upon the bed, receiving his forehead, and covering the greatest part of both his eyes, gently sunk down with his head (his elbow giving way backwards) till his nose touch’d the quilt;——his left arm hung insensible over the side of the bed, his knuckles reclining upon the handle of the chamber-pot, which peep’d out beyond the valance—his right leg (his left being drawn up towards his body) hung half over the side of the bed, the edge of it pressing upon his shin-bone—He felt it not. A fix’d, inflexible sorrow took possession of every line of his face.—He sigh’d once——heaved his breast often—but utter’d not a word.

Tristram leaves him frozen in this position for some fifty pages, interrupted by numerous digressions, and a new Book. Walter is revived in Book 4, chapter 2, with the same meticulous anatomical detail:

My father lay stretched across the bed as still as if the hand of death had pushed him down, for a full hour and a half, before he began to play upon the floor with the toe of that foot which hung over the bed-side; my uncle Toby’s heart was a pound lighter for it.———In a few moments, his left-hand, the knuckles of which had all the time reclined upon the handle of the chamber-pot, came to its feeling—he thrust it a little more within the valance—drew up his hand, when he had done, into his bosom—gave a hem!

Uncle Toby and the Widow Wadman (Charles Robert Leslie)

By now Uncle Toby is at hand, and his smile has a soothing effect: ‘My father, in turning his eyes, was struck with such a gleam of sunshine in his face, as melted down the sullenness of his grief in a moment.’

All through Tristram Shandy we’re never allowed to forget about the human body, its peculiarities and its imperfections. The bed, too, is seldom far away. This is a novel, after all, that gives as much attention to conception and birth as a bed’s other common settings, love, sleep and death. Bring bodies and beds together and you have the making of all kinds of innovative fiction, both comic and consequential. And, what Samuel Taylor Coleridge says of Sterne, ‘acknowledgement of the hollowness and farce of the world, and its disproportion to the godlike within us’.

Leave a Reply