There’s something faintly ridiculous about the phrase ‘librarian as hero’. But just occasionally librarians come along who, if not exactly heroic, at least have the capacity to astonish their successors with the number and breadth of their achievements. John Ballinger (1860-1933) was one such example.

Ballinger was the Librarian of the Cardiff Free Library1 and the first Librarian of the National Library of Wales (1907-1930). He was one of the most distinguished professional librarians of his time, and his influence on the public libraries of Wales and on the early development of the National Library was crucial. 160 years after his birth is a good time to recall the man and his successes – and some of his weak spots.

Some work has been done on John Ballinger by scholars. Mark Bloomfield published an article on his professional work2, a very detailed bibliography3, including ‘Some biographical speculations’, and an article in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. David Jenkins’s history of the National Library of Wales4 considers in detail the origins and early development of the Library, and Ballinger’s part in them. Turning to original sources, the National Library has a modest collection of John Ballinger’s papers, but they’re disappointingly bureaucratic in nature and contain little that’s personal. This is unfortunate, since it is his personality that is the most intriguing aspect of him.

There exists an oral tradition, especially within the National Library, about Ballinger. Mark Bloomfield consulted some of those who knew Ballinger well, including Gildas Tibbott, the head of the Department of Manuscripts and Records, and Beatrice Davies, Ballinger’s personal secretary.

My own investigations are mainly based on secondary sources; they’re therefore open to contradiction and expansion. I’ll try to give general overview of Ballinger’s life and work, and try to evaluate his significance – not only for his own time but also to us today, because some interesting parallels emerge with our contemporary experience.

Little is known about John Ballinger’s antecedents and early years. He was born in Pontnewynydd, near Pontypool, Monmouthshire, on 12 May 1860. He was the son of an engineer, Henry Ballinger, who came from Whitchurch, on the Herefordshire / Monmouthshire border.5 Henry lost his job at the Pontnewynydd Iron Works and moved to Whitchurch in Cardiff, where he found employment in the Melingriffiths Works. John’s mother came from Monmouthshire. It’s clear that the family was not Welsh-speaking, and that John Ballinger received little if any education in Welsh.

John lost his father at age of six. Probably as a result his formal education was meagre. He went to elementary school in Canton, but by the age of fourteen had ceased attending school, and after a year of private education he was looking for employment. However, we know he did attend evening classes, and read widely on his own account, because he became proficient in French, geology, sculpture and other subjects.

The main features of these years – the early loss of his father, the lack of Welsh, the autodidacticism and lack of a university education – had important influences on his later career, and very possibly on his character and his relationships with colleagues.

The next few years are nothing less than astonishing. In 1875 at the age of fifteen he became an assistant in the Cardiff Free Library. Only five years later, after an initial failure with Swansea Public Library, he applied for and gained the post of Librarian in the public library in Doncaster, south Yorkshire. Even considering the relatively small size of the library at this period, it was a remarkable position for a man of twenty. He must have been an impressive figure, with a thorough knowledge of best library practice, a driving ambition to advance himself, and the huge self-confidence that seems to have been one of his most consistent traits.

At Doncaster John Ballinger built a reputation for progressive librarianship. One of his first actions was to circulate all the ratepayers who had not joined the library: something too few librarians make a practice of even today. He attracted many gifts of material from many sources. He started a column, ‘About books’, in the local newspaper, the Doncaster Chronicle, drawing attention to literature he thought was worth reading.

In 1884, perhaps to be close to his family and future wife Amy (by whom he had three sons and a daughter) or maybe through frustration with the library authorities, he applied to become the Librarian of the Cardiff Free Library. Again, he was successful. So began a glittering career in what soon became one of the leading public library services in the UK.

John Ballinger was twenty-four years old when he came back to Cardiff. According to his assistant Archibald Sparke he looked more like fifty years old on account of his long black beard. When it was founded in 1863 Cardiff was the first public library to be established in Wales under the provisions of the 1850 Public Libraries Act. The new library building, now the Old Library, had been opened in the Hayes two years before. John Ballinger set about using this energetic start as the basis for building a powerful and innovative library service. Statistics indicate the extent of his success. During his period as Librarian the number of books borrowed rose from 7,000 to 750,000 a year. By 1905, 100,000 volumes had been amassed in the collections; 20,000 of these were Wales-related. There were also 2,000 manuscripts. Ballinger was helped by talented colleagues, a supportive committee, and of course the wealth of Cardiff, whose economy was at its peak at this time.

These are some of Ballinger’s achievements in Cardiff.

He was an energetic bibliographer, producing printed catalogues of music (1888), and Welsh books (1898) based on the Library’s collections. The latter was prepared in collaboration with James Ifano Jones. It contained 12,000 entries and represented a major contribution to Welsh bibliography, strengthening Cardiff’s case later on to be home of the National Library of Wales. Ballinger also published a catalogue of embossed books for the blind (1889).

He was also enthusiastic about exhibitions as a means of publicising his collections. One of the most significant was one on the Bible in Wales. This was opened by Sir John Williams on 1 March 1904 to mark the centenary of the British and Foreign Bible Society. A catalogue was published in 1906: with its introduction and detailed annotations this too became a standard work.6 Later, Ifano Jones, Chief Assistant in Reference Department in Cardiff Public Library, was to claim publicly that he and not John Ballinger was responsible for the historical introduction to the volume.

But the strongest of Ballinger’s enthusiasms was for education, and the part libraries could play in helping children learn. He encouraged children to come into Cardiff libraries; he gave lectures for children, illustrated with lantern slides and models, and introduced children’s ‘reading halls’ in new library buildings. His efforts were so successful that libraries became established in all Cardiff schools. In a paper to a Library Association conference in 1898 entitled ‘School children in the public libraries’, he told fellow librarians ‘to stop burying your heads in organisation and administration and to work for the strongest relations between libraries and education’.

The library service flourished and expanded under Ballinger’s leadership. New branch libraries were opened: in Cathays (1906, a particularly fine Carnegie building), Canton (1906, also a Carnegie building) and Roath (1901).

New technologies excited librarians then as much as they do today. In 1907 the Cardiff Library started a telephone enquiry service for businessmen, possibly the first of its kind in UK. Ballinger also used speaking tubes to communicate with staff downstairs, and there were mirrors – an early version of CCTV cameras – to supervise readers, especially, according to Bloomfield, ‘the women who tried to hog or steal the periodicals by hiding them under their voluminous skirts. It is reassuring to know that the mirrors were overhead’.

According to Archibald Sparke’s reminiscences John Ballinger was a hard taskmaster: he would not permit his staff to do any work other than their strict duties, and he made them work long hours, including on Sundays.

While at Cardiff Ballinger became active professionally. He joined Library Association committees and agitated for repeal of the legal limit of one penny in the pound on the local rate for public libraries; he campaigned on the Treasury treatment of tax on library buildings; he fought against censorship of newspapers (the racing section was frequently excised from library copies); and he advocated open access for lending libraries at a time when closed access was the norm. He edited the Public library journal and was a member of the Library Association Council for many years, serving as President in 1922-23.

All the while a stream of pamphlets and lectures on professional library matters poured forth from Ballinger’s pen. His publications of lasting value were bibliographical. Some of these were minor, often stimulated by collections or items newly acquired, such as Rhys Prichard’s Canwyll y Cymry); others were larger-scale catalogues and bibliographies.

While in Cardiff John Ballinger must have been keeping a careful eye on the movement to set up a National Library of Wales. The movement is usually reckoned to have had its origin in the National Eisteddfod held at Mold in 1873, when a committee was set up to work towards establishing a National Library. The movement was revived after T.E. Ellis MP re-established the committee in 1896, and a campaign led by John Herbert Lewis MP was begun to persuade the government to recognise the need for a national library and a national museum for Wales. In 1904 Sir Isambard Owen presented a report to Parliament arguing the case, and finally Austen Chamberlain, Tory Chancellor of the Exchequer, accepted the recommendations.

As the government began to show signs of yielding, and especially as the possibility of a separate library emerged, John Ballinger must have started to wonder about his own chances of becoming the first Librarian of the National Library of Wales. He was by far the best-known librarian in Wales, with a solid record of achievement in the country’s largest public library.

The location of the new national library and museum was disputed, and a committee of the Privy Council was asked to adjudicate between the rival towns. A fierce struggle took place between Cardiff and Aberystwyth. Cardiff wanted both museum and library, Aberystwyth the library alone. Battle lines were drawn up and rival prospectuses printed. Cardiff could point to its being the focus of Wales’s main concentration of population and of industry, and to the existence of the collections of the Free Library (Welsh collections had been built up since 1886). Aberystwyth drew attention to the nucleus of a Welsh collection already in existence in the University College, the availability of a site, purchased by Lord Rendel, a central location in mid-Wales within a Welsh-speaking area, and above all, Sir John Williams’s promised donation of his pre-eminent collection of Welsh books and manuscripts.

As we’ve seen, Sir John Williams and John Ballinger were known to each another. John Williams had opened the Bible in Wales exhibition in 1904. Both men belonged to Cymdeithas Llên Cymru, a group of six bibliophiles who aimed to publish fine editions of Welsh texts (another member was J.H. Davies, Registrar, later Principal of the University College of Wales and the original Secretary of the National Library). This group had begun to meet in 1900. They shared a common interest in Welsh bibliography, John Williams being the leading collector of his day.

In the J.H. Davies collection in National Library is a letter written by John Williams in May 1904 to Davies, recording a conversation John Williams had with John Ballinger in Cardiff, at the time of the competition for the location of the National Library7. Ballinger had told John Williams he thought that Aberystwyth would win the fight. In the letter Williams asks J.H. Davies: ‘What do you think of getting [Ballinger] to Aberystwyth in time?’

It appears that both John Williams and J.H. Davies sought John Ballinger’s assistance at an early stage on establishing systems in the National Library. For example, in early 1908 advice was sought on the need to write statutes and to secure accommodation outside the College in order to secure a government grant.

There’s another piece of evidence that helps us link John Ballinger with the post of Librarian of the National Library: a ‘dog that failed to bark in the night’. This is the strange public silence from Ballinger in support of Cardiff’s case to be the Library’s home. The case intended to call in evidence certain witnesses. John Ballinger’s evidence could have been compelling, and he had some powerful ideas: for example, he wanted the new National Library to establish a lending service, so that all Wales could benefit. But none of this evidence was published. In fact John Ballinger did and said nothing publicly to advance Cardiff’s claims, despite his personal misgivings about Aberystwyth’s case. On 10 June 1905 the decision on location was announced: Cardiff was to receive the Museum, Aberystwyth the Library. The two Royal Charters were granted on 19 March 1907, and the National Library of Wales began to be a reality, over thirty years after it was first planned.

At its first meeting on 29 May 1908 the Council of the National Library selected a committee to appoint a Librarian. The committee consisted of the Officers and T.F. Roberts, Principal of the University College in Aberystwyth. It met in the House of Commons on 9 July and agreed that Sir John Williams should ask John Ballinger whether he would accept the post of Librarian if it were offered to him, and on what terms. There was therefore to be no open competition.

The circumstantial evidence, taken together, suggests that a deal might have been struck earlier between John Williams and John Ballinger, based on John Williams’s understanding that there was no better candidate available than Ballinger, and John Ballinger’s realisation that Cardiff was not going to win the battle for the site of the Library. In exchange for keeping a low profile during the struggle between Cardiff and Aberystwyth, Ballinger would be offered the Librarianship of the National Library, and without competition. Remember that this was long before Nolan principles governed the selection of public officers.

When offered the post by John Williams, Ballinger replied: ‘The prospect of helping to lay down the lines for a great library is very alluring and, should the Council decide to call upon me, the utmost power I possess will be devoted to the work’.

Such was John Williams’s influence among his fellow campaigners for the National Library at Aberystwyth that the new Council went along willingly with the Selection Committee’s decision. At a meeting on 28 August 1908 it resolved not to advertise, but that at its next meeting it should appoint a Librarian at a salary of £600. A government grant was then secured to pay the salary: another deal was reached, this time between Herbert Lewis and John Williams, and the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Lloyd George. On 14 October 1908, the day after the meeting between John Williams and Lloyd George, John Ballinger was unanimously appointed by the Council as Chief Librarian. It was reported at the first meeting of the Court of Governors on 11 December that he had accepted the post, and that he would start his duties on 1 January 1909, at a salary of £600 a year plus pension (he had earned £500 in Cardiff).

Bloomfield’s comment on this process is well expressed: ‘Ballinger cultivated his friends and acquaintances carefully. Shall we say, he harmonised his interests remarkably well with those who had the power and influence to assist him on his way.’

J.H. Davies wrote to John Ballinger on 16 October: ‘I need not tell you what a pure joy it is to me that you have been appointed Librarian. I feel that the success of the Library is assured, and that you will succeed in doing for Wales through the National Library, what has never been done before for any country.’

There may have been no competition, but that did not mean that there were no other competitors. One obvious candidate would have been John Glyn Davies (1870-1953), who had acted as the (very poorly paid) Librarian of the Welsh Library in the University College of Wales, Aberystwyth. But he was a complex and awkward character, who, unlike John Ballinger, had not succeeded in retaining the confidence of those in whose laps his fate lay. The end to his Aberystwyth career – he went to Liverpool in June 1907 – was sad. Disillusioned by his treatment within the College, and the lack of enthusiasm shown to him as a potential National Librarian, he decided to take revenge. In David Jenkins’s words, ‘on his way to the College he purchased four pennyworth of paraffin oil, and in the seclusion of his office in the College Tower on a quiet Saturday afternoon, when all the others were at rest or play, he burnt his complete catalogue of Welsh books, running into several thousand cards’. (Glyn Davies, however, sent Ballinger a warm and helpful letter of congratulation on his appointment.)

Another candidate might have been the palaeographer and printer John Gwenogvryn Evans (1852-1930). He’d been associated with the National Library of Wales campaign for many years. He was an expert on Welsh manuscripts and had published the standard list of them.8 We know he was antagonistic to John Ballinger’s appointment.

A third candidate might have been the librarian of Swansea, and historian of the Neath valley, D. Rhys Phillips.

John Williams, however, knew that he ‘had his man’. John Ballinger too must have been certain that he had done the right thing. On the other hand, his appointment may well have exposed differences between the founding fathers, and stored trouble for the future.

John Ballinger left Cardiff to an appreciative farewell. Tribute was paid to his ‘unusual degree of grit, ability and dogged perseverance, whereby he sought to bring the library and its treasures to the very doors of the people; to make the institutions under his charge a vital and indispensable part of city life; and to bring all classes of the community into close and intimate relations with it’.

And so Ballinger moved to live in Aberystwyth, to begin work in the Library’s temporary home in the Assembly Rooms in Laura Place on 1 January 1909. He was forty-eight years old.

In describing and evaluating John Ballinger’s contribution to the National Library one difficult problem arises: what should be attributed to him and what to the Officers and Council? It’s clear that in the early years the latter were both influential and interventionist. Nevertheless, there can be no doubt that Ballinger was primarily responsible for creating from nothing – he began in Laura Place with only a table and a chair, not even any books or shelves – something that resembled what we can see today: half a million books, scores of thousands of manuscripts, and a building nearly complete.

What were John Ballinger’s achievements during his long, 21-year tenure?

One of the most pressing tasks in the first years was collection building. A distinct advantage here was that Sir John Williams had pledged his huge personal library to Aberystwyth. Almost as soon as John Ballinger arrived in Laura Place in January 1909 he was faced with the considerable task of transporting 24,500 volumes from William’s home, Plas Llanstephan. Another, even more important collection soon followed. W.R.M. Wynne of Peniarth, the owner of the Hengwrt-Peniarth collection, died a few weeks after John Ballinger started, on 5 February, and so this crucial manuscript collection became the property of John Williams (he had bought it earlier, subject to the life interest of Wynne and his brother).

Sir John Williams was not the only builder of the early collections – J.H. Davies was another – but we can attribute to John Ballinger much of the success in creating a library of major importance.

He attracted a large number of donations on his own account. One of his first acts was to write to editors of all Welsh newspapers and periodicals inviting them to send one free copy: what we would now call voluntary deposit. Appeals to the public for material were frequent. Ballinger reported that a ‘Mr Morris of Welshpool recovered 3 (rare) volumes of the Salopian Journal and Shrewsbury Chronicle from a fishmonger’s barrow: part of one of the volumes had been torn away to wrap fish, but the other two volumes are complete’.

Ballinger made use of the members of the Court of Governors to track down desiderata. He started exchange of publication schemes. He negotiated the acquisition of key collections, such as the Iolo Morganwg collection from the Llanover estate, the Mostyn manuscripts, John Thomas’s photographs and landed estates records deposited after the First World War. He began collections of ephemera, some collected in his book Gleanings from a printer’s file (1928). In 1911 he tried to have a Welsh Public Record Office established in Aberystwyth. That attempt failed, but Ballinger succeeded in gaining legal deposit status for UK printed publications, with the passing of the Copyright Act 1911, after a difficult and skilfully waged campaign. Of all Ballinger’s achievements this is the one of most significance for the later development of the National Library and its usefulness to its readers.

Ballinger may have been responsible for the remarkably broad and eclectic collecting policy adopted by the Library almost from the start. His words about the collecting of art, ‘the pictures need not necessarily be of value as works of art, as long as they illustrate the subject’, are not far from the Library’s contemporary policy. It was his idea to create a portrait collection, and to collect picture postcards for the evidence they contained about Wales.

A second priority was building the staff. The staff was naturally small in number, until after the First World War, but Ballinger succeeded in attracting talented people.

Among the early assistants were Richard Ellis and the poet T. Gwynn Jones. Unfortunately, some of them were talented in fields Ballinger found inexplicable or irrelevant. He was particularly dismissive of scholarship when it was not required for library work. In fact, he felt, in the words of David Jenkins, ‘little sympathy with the traditional scholar-librarian, being fully entrenched on the side of the new class of librarians, whose primary concern was the speedy production of book catalogues based on professionally accepted rules. Their objective was to provide a quick and efficient service for readers rather than develop their own academic instincts’.

By 1914, the staff had grown to 14. More came after the War, including in 1919 William Llewelyn Davies, who followed John Ballinger as Librarian in 1930.

Though, as we’ll see, his relationships with some of his staff were not always harmonious, Ballinger placed a great deal of emphasis on their training and development. He initiated a National Library of Wales trainee scheme from 1919; for ten years summer schools were organised for junior librarians.

Ballinger was responsible for the tripartite division of work and staff in the Library, between printed books, manuscripts and prints and drawings, a division that survived in its essentials for ninety years.

The third major concern in the early years, of course, was constructing and funding the building that was to occupy the Grogythan site given by Lord Rendel. Following an architectural competition, won by Sidney Greenslade, the first building contract was signed in May 1911 and the ceremony to lay the foundation stone held on 15 July 1911, in the company of the King and Queen. The American Ambassador was welcomed to the building site in November 1912. A building fund was established, money attracted from the Treasury and a public appeal launched. John Williams and many others promoted the appeal. Perhaps the most assiduous was Daniel Lleufer Thomas, who worked tirelessly to persuade miners and quarrymen to contribute: a remarkable 105,959 contributions were elicited from miners’ lodges and institutes. So successful was all this work that Ballinger, his staff and collections were able to move from Laura Place to the new building in March 1916. The Court of Governors held its first meeting there on 27 May 1916, and in August David Lloyd George paid a visit to receive thanks for his financial assistance.

Ballinger’s personal role in the planning and funding the building is difficult to disentangle from that of others, but we can be sure that he was instrumental in the effort to win funds from the Treasury for maintenance, binding and cataloguing, once the building was opened, and he certainly made great efforts to promote the appeal.

The new building allowed Ballinger to return to his interest in exhibitions. Even before the move to Penglais he had staged an exhibition of John Williams’s manuscripts and rare books, in 1909. The new Exhibition Hall attracted over 16,000 visitors between May and September 1922.

It is easier to see Ballinger’s distinctive influence in the early emphasis on what we would call outreach policies. In his first speech to the Court of Governors on 11 December 1908

he had given a great deal of thought to the question as to what a National Library of Wales was to be, and if they would look at the Charter they would find that it had been drawn in such a way as to allow considerable latitude with regard to the circulation of duplicates for educational and research purposes; but it was a matter which would have to be carefully considered, and extremely rare books should not under any circumstances go out of the National Library. He hoped, by circulating duplicates and triplicates, to take the benefits of the National Library into the remotest hamlet in the Principality, and to make it a real and living institution by putting it within the reach of any person who could be duly accredited. Within a reasonable time it might be possible to initiate a system of that sort. Such a system would overcome very considerable difficulties; and enable a very large number of people in Wales to do work which in itself perhaps was not very great, but in the aggregate would have the effect of producing a higher standard of intellectual attainment which would be a gratifying result of the establishment of the National Library.

The duplicate loans service was provided for in the original Royal Charter. In 1912 a Treasury grant was secured to launch a lending scheme. In the First World War loans were made to the armed forces, at home and abroad. Book boxes were sent over many years to adult education classes, as Chris Baggs has documented, starting in 1914 with loans to tutorial classes in the University College of North Wales in Bangor.9 By 1935-36 the Library was lending 9,697 books to 374 classes. Ballinger also suggested that National Library should act as a clearing-house for school books in Wales.

Other specialist services owe their origin to Ballinger’s professional interests, notably the printing press, bought originally to produce catalogue cards for the National Library and for other libraries (here he was well ahead of his time), and the bindery established under the Norwegian Carl Hanson in 1911.

All this time Ballinger was active in the wider Welsh library scene. He was dedicated to the cause of professional co-operation and instrumental in arranging the 1925 conference that led to a Regional Libraries Scheme for Wales and Monmouthshire in 1932, its bureau located in the National Library of Wales.

He was also active in the academic community in Wales. He was the first Chairman of the Board of the University of Wales Press, established following the Haldane Report (1918). The Board met for the first time in 1922, and Ballinger was its only member with no formal connection with the University of Wales.

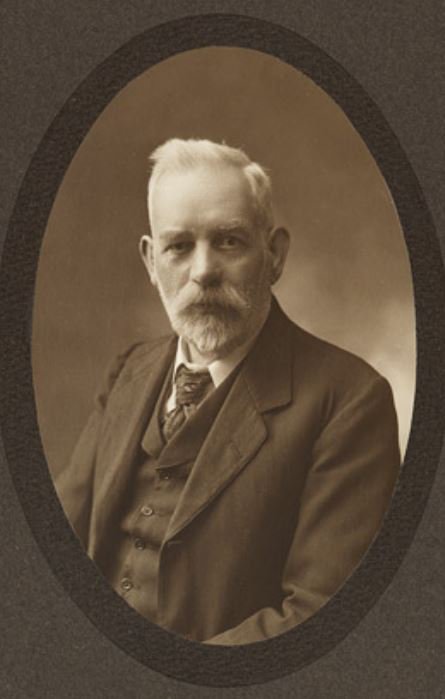

What was Ballinger like as a man? The physical evidence is suggestive. The bronze plaque in the National Library by the leading Welsh sculptor Sir William Goscombe John dates from Ballinger’s very earliest time in the Library, 1908. Bloomfield suggests a likeness to George V: ‘the alert, bold gaze of a man who is very sure of himself’; ‘like the commander of some battle cruiser’. Photographs of him in mid- and later life show the same determination, perhaps also a lack of humour and, in the later pictures, a hint of isolation and loneliness, perhaps exacerbated by ill-health and the horror of losing his son Henry in action in the First World War.

An undeniable characteristic was high energy. In his obituary William Llewelyn Davies said, ‘he had enthusiasm, driving power and the capacity for hard work’. He was also fertile in his professional invention: a progressive, many of whose innovations have proved remarkably long-lived, or are being rediscovered. David Jenkins called him ‘a visionary and a pragmatist’, Bloomfield ‘a peg that found the right holes’.

But there was another, less attractive side to his character. He was noted for a bad temper. It was usually kept under firm control, and was, according to Ernest Savage, accentuated by bad health: Ballinger was a diabetic, and later in life lost much of his hearing and sight. Worse, perhaps, he was an instinctive authoritarian. Admittedly such a tendency was not untypical of that period: John Ballinger was a child of his Victorian times. But even after making allowances it seems that he was an unusually formidable and exacting master. It was a reputation that was well known. There is a story that the parents of Aberystwyth would threaten their children with John Ballinger if they misbehaved.

His treatment of his staff could be high-handed and unsympathetic. In Cardiff Archibald Sparke was not allowed to do any other work than his library duties: he was rebuked for taking part in a church club play, and when he wrote an article for a local paper he was upbraided by John Ballinger for ‘usurping the position of the Chief Librarian’. In the National Library his first assistant Richard Ellis, who was paid £3 a week, was driven away as being too scholarly (he was an expert on Edward Lhuyd), and there were repeated clashes with T. Gwynn Jones: Ballinger had no sympathy with his literary aspirations and counselled Jones to concentrate on writing catalogue cards rather than poems. In short, Ballinger was prickly and not easy to get on with. By contrast his senior assistant William Llewelyn Davies was well liked: he was a Welsh speaker, a scholar, popular and debonair.

Gildas Tibbott, who worked with John Ballinger between 1924 and 1930, said in a letter to Bloomfield in 1975 ‘he was a stern and awe-inspiring figure who ruled with a rod of iron; if he had a sense of humour, he never displayed it in the presence of his subordinates’.

In a letter to Bloomfield J. H. E. Briggs, another colleague between 1923 and 1925, recalled in 1971, ‘… most people in contact with him seemed scared stiff of him. His deafness helped him to avoid hearing things he did not want to hear. He could be abominably rude, but perhaps the diabetes from which he suffered was partly responsible. He was a dictator, but was expert in window dressing, and if he wished he could and did impress visitors, and was able to obtain valuable donations of money and books.’

Ballinger was a poor delegator, and tended in any case to work too hard. In 1912 this lead to a nervous breakdown. He was told to take complete rest, and went to Switzerland for two months to recuperate. This was a difficult period for him. Gwenogvryn Evans, not a man to mince his words, had written to him saying, ‘… you suffer acutely from the lust of power. You want to have everything in your hands and [you have] apparently worked yourself into the belief that no-one knows anything but you.’ In another letter he advised Ballinger, ‘I would urge you to make fellow workers of your assistants …it is better to lead than to drive … Personally I have noticed a great change in your outward manner – you have developed a pomposity which you had not when you came to Aberystwyth. Now if you covet a Knighthood or a C.B. … you have set about it in the wrong way.’

Mention has already been made of Ballinger’s taking the credit for the work of Ifano Jones. He is also alleged to have stolen T. Gwynn Jones’s ideas and presented then as his own.

Some of these traits may have been connected with a sense of inferiority. That was certainly the opinion of Gildas Tibbott: ‘… an unconscious inferiority complex resulting partly from his lack of academic qualifications … and his inability to speak Welsh, so essential in an institution such as the National Library of Wales’.

Despite his professional avant-gardism Ballinger seems to have held highly conventional values, at least according to Bloomfield, after analysing his views on morality gleaned from his columns in the Doncaster Chronicle. The lack of a sense of humour was debilitating: ‘[His] lack of humour and austere sense of mission repelled many of his associates’, reported Ernest Savage. Summing up his character Bloomfield says, ‘Ballinger was a high-minded Victorian whose faults and virtues stemmed from what is now regarded as an over-serious view of life’.

For all his failings John Ballinger clearly retained the confidence of the President and Officers of the Library. He was due to retire in May 1925, but his term was extended for one year, then year by year till 1930. But by now his supporters, the pioneers of the Library, were leaving the scene. Sir John Williams and J.H. Davies died in 1926; Herbert Lewis retired from public life after a serious accident in 1925 and died in 1933. In May 1928 a committee was appointed to consider a successor. This time the post was advertised, and there were seventeen applications. Short-listing led to a controversy about whether a Welsh speaker should be appointed, a controversy joined publicly at one point by Saunders Lewis. In the end the post went to William Llewelyn Davies.

According to Bloomfield Ballinger ‘suffered a domestic accident in which his beard was burned, causing him to miss the meeting of the Court of Governors on 15 January 1930 at which his successor was appointed (against his wish)’. This incident may be associated with drink problems, which feature strongly in the oral tradition about Ballinger’s final years. He retired on 31 May 1930, after 21 years and five months in office.

The Court of Governors thanked him for ‘devoting all your energies to the formation and administration of a national institution which, from comparatively small beginnings, has now become one of the great libraries of the world … due in no small measure to your abundant energy, driving power, capacity for taking pains, and ability not only to discover, but also to secure valuable collections for the Library.’ In reciting his many achievements the members singled out two for special mention: the securing of legal deposit status, and gaining ‘the continued interest and support of the general public’. They wished Ballinger a happy retirement and hoped they could still call on his ‘ripe experience and sage advice’.

Ballinger was by now loaded with honours: an honorary MA from the University of Wales (1909), a CBE (1920), honorary Fellow of the Library Association (1929), and a knighthood (1 January 1930). The Medal of the Honorary Society of Cymmrodorion followed in 1932.

He retired to Harwarden, Flintshire, where he gave advice to St Deiniol’s Library (now Gladstone’s Library). He also resumed his publishing career and his commitment to the historical bibliography of Wales: between May 1930 and May 1931 he edited five facsimile editions of 17th century Welsh books for the University Press, with bibliographical introductions.10

But Ballinger’s health was poor, he was now almost blind, and he died on 8 January 1933. He was buried in the churchyard in Hawarden. His wife Amy died very soon afterwards, on 28 October 1933.

The final word will rest with John Herbert Lewis. It is a just summary of John Ballinger’s achievement, but at the same time contains just enough bathos to cause us (but probably not John Ballinger) to smile:

‘[The National Library of Wales] is as it were our temple of Vesta wherein burns the flame which may never be extinguished, and our friend Mr Ballinger here is the Vestal Virgin whose task it is for ever to feed the flame’.11

REFERENCES

1 Now Cardiff Public Library; the Free Library building in The Hayes is now known as the ‘Old Library’.

2 M.A. Bloomfield, ‘Sir John Ballinger, librarian and educator’, Library History, vol. 3, no. 1, Spring 1973, p.1-27.

3 M.A. Bloomfield, Sir John Ballinger: an annotated bibliography, 1998.

4 David Jenkins, A refuge in peace and war: the National Library of Wales to 1952, Aberystwyth: National Library of Wales, 2002.

5 Information from John Ballinger, his great-grandson.

6 [John Ballinger and James Ifano Jones], The Bible in Wales: a study in the history of the Welsh people, London: Sotheran, 1906.

7 7 May 1904, National Library of Wales, Cwrtmawr, J.H. Davies Correspondence.

8 Reports on MSS in the Welsh language, HMSO, 1898-1910.

9 C.M. Baggs, ‘The National Library of Wales book box scheme and the South Wales coalfield’, National Library of Wales Journal, vol. 30, 1997, p. 207-29.

10 These editions were severely criticised for their errors by G.J. Williams in Y Llenor (1930).

11 J. Herbert Lewis, The National Library of Wales: a review of five years, 1921

Note This is a revised version of an English translation of an article published as ‘John Ballinger’ in Taliesin, 162, Hydref 2007, t. 219-34.

Leave a Reply