In 2012 the Huddersfield poet Simon Armitage published a book called Walking home, about a trip he made on foot two years earlier from north to south along the length of the Pennine Way. He started without a penny in his pocket, paying for his accommodation and meals through poetry readings he gave at various points on the way. The book is a rueful and humorous description of a frequently wet and miserable journey.

In 2012 the Huddersfield poet Simon Armitage published a book called Walking home, about a trip he made on foot two years earlier from north to south along the length of the Pennine Way. He started without a penny in his pocket, paying for his accommodation and meals through poetry readings he gave at various points on the way. The book is a rueful and humorous description of a frequently wet and miserable journey.

This summer Simon has been repeating the trick, this time on the South West Coast Path, from Minehead to Land’s End and beyond, for a companion book to be called Walking away. Again he’s been giving a string of poetry readings, in venues at regular locations – cafes, bars, libraries and galleries – along the north Devon and Cornish coast: entry is free, and the audience pay what they think the wandering poet is worth.

Poets often make energetic walkers. William Wordsworth comes to mind immediately – but as far as I know, like many others, he kept his walking and his versifying as separate activities, recollecting what he experienced on the open air later in the tranquillity of his study. Simon Armitage’s more integrated mix of rhyming and rambling seems to have a closer parallel in the seventeenth century Japanese master of the haiku, Bashō.

Probably Bashō ‘s best known work is The narrow road to the deep north, a short account of a journey he made on foot, starting on 27 March 1689, after selling his house in Edo (now Tokyo). Already a highly accomplished and published poet as well as an experienced long-distance walker, he was 45 years old when he set out. He spent six months on his tour of the northern parts of Honshu, keeping close to the east coast to begin with – he spends a night in Fukushima – before crossing to the west coast and ending at Ogaki – in total, a trip of some 1,200 miles.

This kind of walking, for its own sake and over such a long time and distance, was uncommon in Japan at the time, and the north of Japan was terra incognita to many who lived further south. It’s clear that for Bashō, who was strongly influenced by Buddhist thought, the deep north represented not only a physical journey but also an opportunity to explore the depths of his own being and of the whole world. He explains in his preface the restlessness that set him once again on his travels:

I have been tempted for a long time by the cloud-moving wind – filled with a long desire to travel … The gods seemed to have possessed my soul and turned it inside out, and roadside images seemed to invite me from every corner, so that it impossible for me to stay idle at home.

After selling his old house Bashō fixes a poem to its threshold:

Behind this door

Now buried in deep grass

A different generation will celebrate

The Festival of Dolls

This passage sets the pattern for what follows throughout the journey: short accounts of Bashō ‘s travels are sprinkled with examples of haiku, his own and those of others, each one artfully attached to its context, so that the whole book is a kind of prose-poem. Each haiku is marked by two characteristics, an indication, often indirect, of the appropriate season of the year, and a ‘breaking word’ that acts as an emotional punctuation mark.

This passage sets the pattern for what follows throughout the journey: short accounts of Bashō ‘s travels are sprinkled with examples of haiku, his own and those of others, each one artfully attached to its context, so that the whole book is a kind of prose-poem. Each haiku is marked by two characteristics, an indication, often indirect, of the appropriate season of the year, and a ‘breaking word’ that acts as an emotional punctuation mark.

Walking with a companion, a fellow-poet called Sora, Bashō travels light: a few clothes, writing equipment and gifts for friends. He tells how tiring he finds the journey, and occasionally an old complaint recurs and causes him pain. The north country is cold and often wet:

How far must I walk

To the village of Kasajima

This endlessly muddy road

Of the early wet season?

Sometimes, lacking the seventeenth century equivalent of TripAdviser, Bashō is unlucky with his accommodation and records his stay in a way that Simon Armitage would surely appreciate:

Bitten by fleas and lice

I slept in a bed,

A horse urinating all the time

Close to my pillow

But on he walks, seeking out shrines, tombs, historic and literary sites, and the stories behind them. He stands in wonder before waterfalls. He lodges at inns and houses and with friends, observing the honesty and hospitality (and sometimes the thoughtlessness) of the people he meets. Occasionally he climbs sacred mountains. He visits well-known sites, like the ‘Murder Stone’ and the islands of Matsushima.

And all the time he reacts to everything he experiences with the transforming precision of the haiku writer. The seventeen syllables of the form balance the extreme self-sufficiency of the Zen life as lived. Bashō quotes a poem by the priest of a temple he visits:

And all the time he reacts to everything he experiences with the transforming precision of the haiku writer. The seventeen syllables of the form balance the extreme self-sufficiency of the Zen life as lived. Bashō quotes a poem by the priest of a temple he visits:

This grassy hermitage,

Hardly any more

Than five feet square,

I would gladly quit

But for the rain.

He leaves in the poet’s hut his own impromptu poem, which reproduces the sentiment but gives it a small twist:

Even the woodpeckers

Have left it untouched

This tiny cottage

In a summer grove.

Bashō inserts haiku into his narrative in all kinds of ways. Poems appear to note a departure; to mark a significant place visited, like a temple; to respond to a natural feature like Mount Kurokami or a man-made marvel like the great gate of Shirakawa, or weather or people encountered on the way; to comment on history or myth associated with places passed through. Poems as objects are treated in many different ways: Bashō writes them to leave for others to find; in response to haikus by predecessors, or to invitations from hosts; as sequences of verses written with his poet friends, like his companion Sora, and handed over as gifts to benefactors.

A typical poem genesis: at the edge of a town Bashō finds an ancient chestnut tree, in whose shade a priest lives in seclusion. This puts him in mind of priests of the past who favoured the chestnut, and he recalls the tree’s sacred association. He takes out pen and paper, writes a note, and then a poem:

The chestnut by the eaves

In magnificent bloom

Passes unnoticed

By men of this world.

One of the most remarkable passages relates Bashō ‘s guided ascent of Mount Gassan:

One of the most remarkable passages relates Bashō ‘s guided ascent of Mount Gassan:

I walked through mists and clouds, breathing the thin air of high altitudes and stepping on slippery ice and snow, till at last through a gateway of clouds, as it seemed, to the very paths of the sun and moon, I reached the summit, completely out of breath and nearly frozen to death. Presently the sun went down and the moon rose glistening in the sky. I spread some leaves on the ground and went to sleep, resting my head on pliant bamboo branches. When, on the following morning, the sun rose again and dispersed the clouds, I went down towards Mount Yudono.

This anticipates by four centuries the ‘new nature writing’ of Robert Macfarlane, who describes the winter night he spent alone on the summit of Ben Hope in The wild places (2007). Rebecca Solnit, in her masterpiece Wanderlust: a history of walking (2001) points out the link with the Shugendo, ‘more or less a Buddhist mountaineering sect’, who treated mountain ascent as a parallel to mental enlightenment (she also notes that the Japanese today are renowned mountaineers).

At his destination, Ogaki, Bashō is reunited with friends, including Sora, who had been forced by illness to leave him earlier. But already he is planning another journey, and soon takes his leaves of them:

As firmly cemented clam-shells

Fall apart in autumn,

So I must take to the road again,

Farewell, my friends.

Does his long northern walking trip leave the poet with a restfulness and contentment that his faith would surely wish for him? The postscript suggests not:

As we turn every corner of the Narrow Road to the Deep North, we sometimes stand up unawares to applaud and we sometimes fall flat to resist the agonizing pains we feel in the depths of our heart.

A few years later, in 1694, as he lay dying of dysentery in Osaka, Bashō wrote a poem that connects his troubled mental state with the restless wanderings of the long-distance walker:

Seized with a disease

Halfway on the road,

My dreams keep revolving

Round the withered moor.

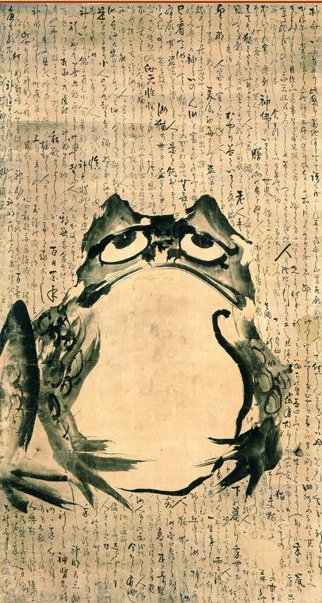

Three years before he set out for the Deep North, in 1686, Bashō published a collection of poems about frogs, and in it what is his best known poem. Here too, though in a quieter way, the mind’s achieved stillness is suddenly broken:

Three years before he set out for the Deep North, in 1686, Bashō published a collection of poems about frogs, and in it what is his best known poem. Here too, though in a quieter way, the mind’s achieved stillness is suddenly broken:

Breaking the silence

Of an ancient pond,

A frog jumped into water –

A deep resonance.

Bashō, it seems, was fated never to find the deep sense of peace that he might have sought in his wanderings.

Note: all translations are by Nobuyuki Yuasa.

Leave a Reply