Today is 29 August, the traditional date, faithtourism reminds me on Twitter, for remembering the Decollation of St John the Baptist. Decollation is a euphemism for having your head violently removed from your body. It’s often used of this particular episode, when Herod Antipas, puppet ruler of Galilee and Perea, ordered John to undergo this procedure (now I’m succumbing to euphemism!) as punishment for a disputed crime.

Biblical sources – all four synoptic gospels – claim that what irked Herod was John’s condemnation of him for divorcing his wife Phasaelis and marrying, illegally, his brother’s wife, Herodias. The historian Josephus gives a more plausible explanation, that Herod suspected John, as a charismatic preacher, of preparing to lead a people’s rebellion against his rule – rather as Ayatollah Khomeini did in Iran in the late 1970s. Josephus says John met his end in prison in Machaerus, a hillfort on the east side of the Dead Sea, now in Jordan. The date is uncertain: possibly around AD 28-29.

Naturally enough, it’s the gospel version that prevailed in the Christian tradition – in particular, the story about how Herod’s daughter Salome (Josephus supplies her name) danced at his birthday party, and requested, at her mother’s suggestion, the head of John to be delivered on a plate, as the ultimate birthday present.

Both scenes – John’s beheading and Salome’s present – became common themes in Christian art. Wonderful late medieval examples survive in the Trevor chapel of All Saints’ Church at Gresford, near Wrexham. It’s a few years since I was last there, but I remember feeling overwhelmed by the size of the building and the richness of its decoration (it benefitted in the late middle-ages from being on the pilgrim route to Holywell).

The two John the Baptist windows at Gresford are clearly by the same artist. They’re thought to date from the first decade of the sixteenth century. The first shows the moment before John loses his head. John lies with his head, bearded and halo’d, resting on a large wooden block. To the left stand two other figures. The first is the gaoler. He has a jutting, stubbly chin and three prominent upper teeth. Under a pith helmet-like hat a long stream of plaited blonde hair flows to his shoulders, but wrinkles round his eye can’t disguise his middle age. A large bunch of keys are just visible. He watches the scene with relish. The central figure is the executioner. He sports a large red squashy hat, a blue robe and more long fair hair, but this is no nobleman. His face, cruel and concentrated, with its sideburns, deep-set eyes and three large teeth, tell the story well enough, even without the huge sword he wields above his head, and the couple of spiked cudgels he keeps close. There’s one more figure in the picture. Her head no longer exists, but this is Salome, with her red dress, holding the platter ready to receive the decollated head. She is a very willing accomplice.

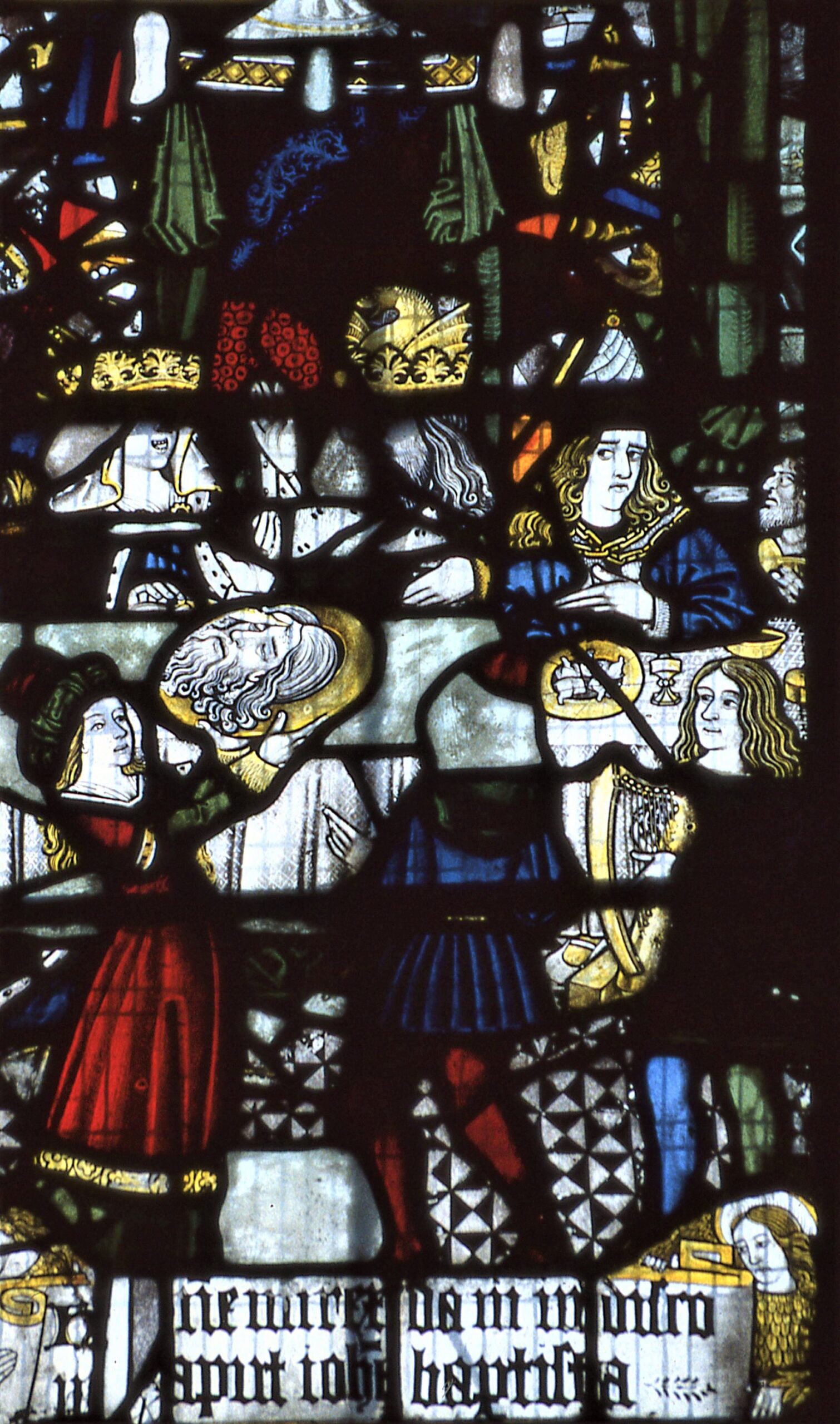

The second window shows scene two, the birthday party. Herod, another recent visitor to the hairdresser, sits feasting at the table. In front of him is a plate of small suckling pigs – eating them, of course, is anathema to the beliefs of the Jews he ruled. On the left sit his wife no. 2, Herodias, crown on head, and another woman, and on the right, the stubbly gaoler. But the scene is dominated by Salome. Like a well-trained waiter, she lifts up the platter and head, like a slab of best beef, ready to plonk them on to the centre of the table. She wears a fine hat and a calm, unconcerned expression on her face. The court harpist, at bottom right, seems to be eying her with admiration as he plucks his strings. Herodias and Herod react in rather different ways. Herodias seems to be prodding John’s head with a knife to see whether she can extract some blood, but Herod’s hands, askant eyes and drawn-down mouth betray his distaste, and possibly panic.

Most versions of these two scenes conform to one of two treatments. Either they play on the piety and sad martyrdom of the victim, or they dwell on the violence and cruelty of the murderers. Caravaggio and Artemisia Gentileschi favoured the latter, and their lead was followed by other, equally grizzly seventeenth century paintings. Later, Gustave Moreau developed an unhealthy obsession with Salome and her pet head, and Oscar Wilde and Richard Strauss had fun with a non-biblical sexualised version of the story (both play and opera were banned in Britain).

The Gresford pictures, though, belong to neither tradition. They’re frankly satirical and comic-strip in feeling. The contemporary artists they best resemble are the cartoonist Martin Rowson and the collagist Cold War Steve. Would the All Saints parishioners not have smiled or even laughed to see them? And might the humour of the two windows have helped to save them from later iconoclasts who were fond of smashing stained glass in churches?

Leave a Reply