Until it was mentioned on the radio the other day I’d never heard of ‘Schubert at the piano’, and apart from being fellow-Austrians I wouldn’t have thought that Gustav Klimt and Franz Schubert had much in common – one an extrovert artist fond of painterly extravagance, the other a reticent musician famously given to introspection and melancholy.

Even though, it seems, he was Klimt’s favourite composer, Schubert wasn’t Klimt’s preference as a painting subject. It was the choice of one of Klimt’s patrons, Nikolaus Dumba. Dumba, born in 1830, was rich industrialist. His father was a Greek merchant who’d moved to Vienna, and he himself owned a large cotton mill. He liked to support the arts and gained a reputation as the ‘Maecenas’ of his age. He made a big donation towards the Musikverein building, and was a friend of Johannes Brahms and Josef Strauss. In 1893 he asked several artists, including Klimt, to produce paintings to adorn his town house. Klimt was invited to paint two works for walls in the Music Room. One was an allegorical picture, ‘Music II’, while the other was ‘Schubert at the piano’.

Dumba was a Schubert enthusiast. He’d made a collection of the composer’s manuscripts, which he bequeathed to the city of Vienna. Asking Klimt to portray Schubert would have been an obvious assignment. The work was completed in 1899, the year before Dumba’s death.

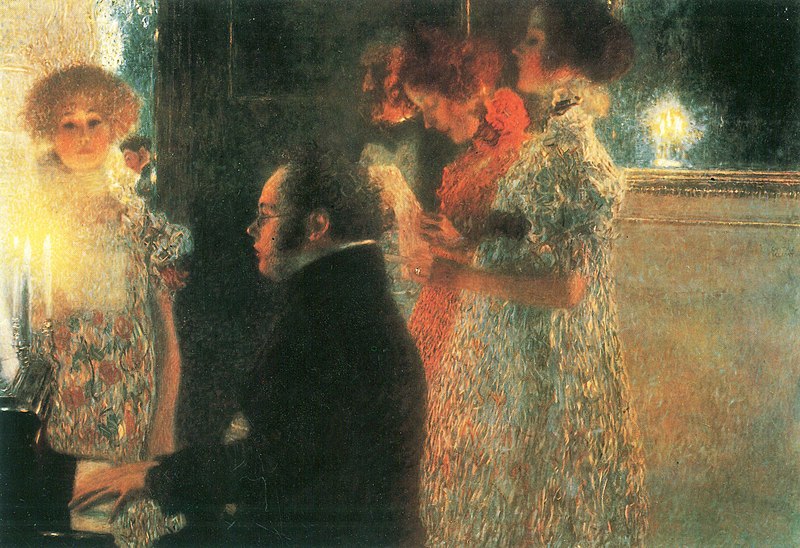

It’s an atmospheric night-time scene, lit by candles. Schubert sits quietly, facing to the left. Only the front of his head is lit, by the light of the candles on the piano. His hands are on the keyboard and his eyes on the music ahead of him. Klimt had clearly studied previous portraits of Schubert closely, and Dumba would have been pleased with the likeness. The best-known portrait, reproduced over and over again, was a watercolour painting by Wilhelm August Rieder, painted in 1825. Klimt follows Riede faithfully: the frizzy hair, large forehead, full mouth, wire glasses and white collar. None of these early portraits, though, show Schubert in profile. That was Klimt’s innovation, perhaps echoing the tradition of silhouettes the Austrians were fond of.

The other striking thing about Schubert in the picture is how inconspicuous he is: a dark figure against a dark background. Without the mask-like face and the trace of white collar you would hardly notice he was there. What Klimt wants us to see is not the retiring composer but the three women who stand around him. (There are also two men, both inconspicuous: one hidden behind the two women, the another apparently in a neighbouring room).

Of the three, it’s the woman on the left who commands our attention – partly because she’s face on to us, but also because the candlelight half-dissolves the surface of her flower-patterned silk gown. Below her bush of red hair she directs an enchanted gaze to the piano keys. This, by tradition, is a portrait of one of Klimt’s many lovers, Marie Zimmermann, who bore him two children and lived on until 1975.

Of the two women on the right, one bends her head over what is possibly the score of Schubert’s music, while the one in front stands erect, her arms held out, as if in a trance of delight. The two wear long, full dresses – one orange, the other steely blue, a-shimmer in the candlelight. Klimt has rendered them in pointillist-like vertical dashes of paint. In a surviving pencil sketch, he dressed them in what he took to be clothes of the early nineteenth century, but the finished painting is far from a faithful reconstruction, because they now wear fashionable dresses of turn-of-the-century Vienna.

Women were certainly present at ‘Schubertiads’, the informal gatherings that met at houses to play and listen to Schubert’s music, but Klimt tilts the balance in favour of them in a similarly ahistorical way.

But these incongruities don’t matter. Klimt melds the different elements of his scene – the intent composer and the rapt admirers, the dark shadows and the glowing candlelight, the gorgeous detailing of the dresses alternating vertically with the blank planes of Schubert’s figure and the surface to the right – into a perfect composition. The painting succeeds in combining the contrasting elements in the music of Franz Schubert, his ecstatic joy in melody and dance, and his profound insight into the ‘tears of things’.

There’s a final unreality to ‘Schubert at the piano’. It’s a painting that doesn’t exist. During the Second World War it was moved for its own safety, along with other paintings by Klimt, to Schloss Immendorf in Lower Austria. But on the very last day of the War retreating German forces set the castle alight and the painting was destroyed. Fortunately, ‘Schubert at the piano’ had become so famous – it was probably the best known of all Klimt’s works after ‘The Kiss’ – that good colour reproductions were made of it.

Leave a Reply