The Auguste Rodin exhibition now at Tate Modern takes you beyond easy assumptions about the artist, based on the best-known works and a few fragments of biography. Rodin’s escape from the conventional beauties of classicism into reconstructing real human bodies came in 1876 with The age of bronze. Its realism scandalised the critics. But that’s just the starting point for this show, which opens up many windows on to his later works. They took him beyond realism, and beyond art-as-object towards art-as-process. What we see is mainly white plaster casts. Rodin valued casts for themselves, apart from the bronzes he used them to create.

The Burghers of Calais has a room to itself. Rodin squeezes maximum expression from the roped-together and about-to-be-executed councillors. Elsewhere there are familiar single figures: several versions of the novelist Balzac, flabby-faced and pot-bellied but heroic, and the headless Walking man. Some figures Rodin deliberately amputates or assembles from different pieces, to echo survivals from Greek and Roman sculpture. But he also makes delicately tinted drawings of women swimming, and creates some works that border on surrealism: a miniature woman hiding out in an antique vessel, and neat rows of ‘abattis’ (giblets): small human hands, arms and legs, which, like an anatomist, Rodin kept in drawers as a reference collection.

We catch glimpses in the show of some of the women in Rodin’s personal and artistic life. Curiously, Gwen John, his model and lover from 1904, is absent, but the exhibition introduces us to Rose Beuret, the seamstress and model who stayed with him for 53 years and finally married him, just before their deaths, Hélène von Nostitz, aristocratic friend and model, Ohta Hisa, Japanese actor and dancer and yet another model, and his fellow-sculptor Camille Claudel.

Camille was born in northern France in 1864. She was already experimenting with shaping clay at the age of twelve, while living with her family in Nogent-sur-Seine. Determined to be an artist, she moved to Paris and joined the Académie Colarossi, one of the few art schools open to women. Very unusually, it allowed women to work from nude male models. Her teacher was Alfred Boucher, a generous helper of artists, who made a sculpture of her reading (she in turn made a bust of him). In 1882 she shared a studio with three women sculptors from Britain, Emily Fawcett, Jessie Lipscomb and Amy Singer.

Boucher left for Rome and left Claudel in the care of Auguste Rodin, who eventually became her lover as well as her teacher and employer. She worked in his studio from 1883, assisting and acting as a model – one piece in the exhibition shows Rodin’s head of Camille, cradled by a left hand added much later – and making her own works. Three years later she won praise (but not a bronze casting) for her large-scale sculpture Shakuntala (Shakuntala, a character in Hindu mythology, was reunited with her partner after many years apart). Its affinity with Rodin’s The kiss is unsurprising, since she had helped him make it. Claudel found making Shakuntala strenuous work: ‘I have two models per day: a woman in the morning, a man in the evening. You can understand how tired I am: I regularly work 12 hours a day, from 7 in the morning until 7 in the evening, and when I get home, it’s impossible for me to remain standing and I go directly to bed.’ Later Claudel produced a revised version, more acceptable to conventional taste, and gave it a new, Roman name, Vertumnus and Pomona.

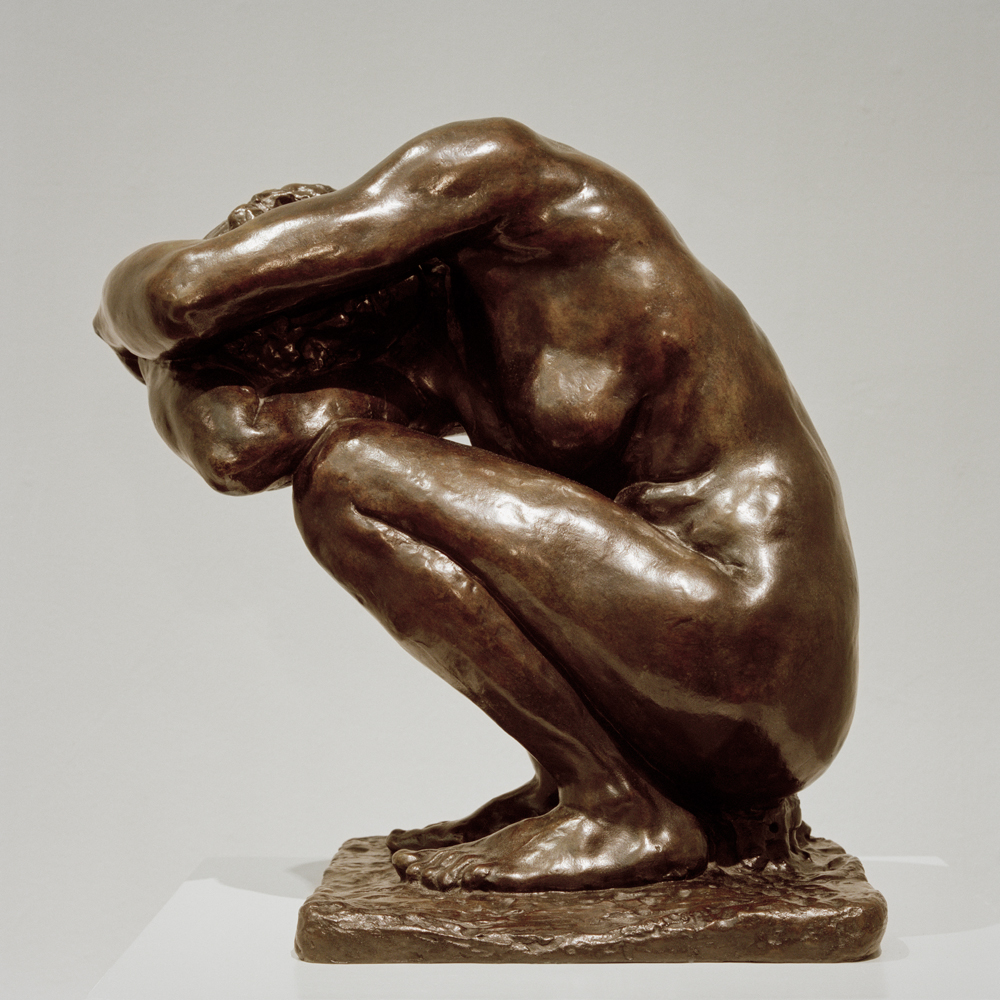

In 1884-5 both Rodin and Claudel produced sculptures of a Crouching woman, using the same model. Rodin’s version is awkward and ‘assembled’. Claudel’s work, taut, compact and muscular, has an ambiguous, coiled look, as if capable of springing into any direction.

By 1892 the relationship between Rodin and Claudel, always tempestuous – he called her ‘ma féroce amie’ – had broken down, as Rodin refused her demands that he commit himself to her exclusively. He continued to assist her, but she left him, to continue working alone, and increasingly she turned against him. The works that followed broke away from Rodin’s heroic style. In The waltz (1893) she shows a liquid, sensuous embrace, in which the naked dancers melt or metamorphose into the turbulent drapes gathered round their legs. The gossips (1893-1905), by contrast, is a domestic group of naked women, chatting round a table, and in Deep thought (c1898) Claudel reduces her subject to a single kneeling figure, her hands raised towards a mantlepiece in front of her.

Rodin’s rejection seems to have provoked not only hostility but feelings of persecution in Claudel. Finally, she suffered a breakdown in 1905, stopped working, and destroyed many of her works. Immediately after her father’s death in 1913, her mother, who had never been sympathetic to her artistic ambitions, and her brother, the reactionary Catholic writer Paul Claudel, who disapproved of her affair with Rodin, had her committed to a mental asylum. Abandoned by her family and forgotten by the public, she died aged 78 in 1943, and was buried in a common grave.

About 90 statues and drawings by Claudel survive – enough to gauge what she achieved in her short career and to imagine what she might have accomplished had the societal and personal pressures on her not cut that career short. (Gwen John was luckier – or tougher – in surviving to create a large and distinctive body of work.) Since the 1980s she’s been rediscovered, in biographies, films and plays. The Musée Camille Claudel opened in Nogent-sur-Seine in 2017 and holds the largest number of her works.

Leave a Reply