One of the many noxious elements making up the miasma of Brexiter thinking is exceptionalism. The idea that Britain is naturally superior to other countries, and that it is strong enough to stand alone against every foe, has deep roots – much deeper than the Battle of Britain, so often trundled out by politicians. If you wanted to find a single event that crystallised this delusion you could do worse than pick the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. Or rather how its outcome was received and represented in Britain.

The victor of Waterloo, Arthur Wellesley, was amply rewarded. He’d already acquired his title of Duke of Wellington, the year before, but quickly amassed other honours, monuments, statues, namings, and in due course he became a notoriously reactionary Prime Minister, in 1828. His deification, like his military career leading up to Waterloo, cemented the thinking that the manifest destiny of the United Kingdom and Ireland – a state only fifteen years old, remember – lay in domination and empire. It also helped to bury the last remains of the dangerous strands of political radicalism in Britain stimulated by the French Revolution. As Linda Colley wrote (years before the arrival to power of Cameron and Johnson),

Waterloo made the world safe for gentlemen again. A British army led by a duke, and officered overwhelmingly by men of landed background who had purchased their commissions, helped destroy a self-made emperor and his legions. Won on the playing fields of Eton it was not, but Waterloo indubitably preserved the social and political prominence of old Etonians and their kind.

Exceptionalism is often accompanied by another idea, that lends legitimacy and weight to it: self-sacrifice. Today that might take the form of the statement, ‘OK, Brexit will disrupt our lives and impoverish us, but it’s worth it in order to regain our sovereignty’. In the past self-sacrifice mean rather more: losing one’s life. In the wars against Napoleon the classic case was Horatio Nelson. Wellington lived on till 1852, but when he died the Poet Laureate Alfred Tennyson wrote a (less than inspired) ode to him than linked triumph and self-sacrifice:

The long self-sacrifice of life is o’er

The great World-victor’s victor will be seen no more

As the Empire waxed and waned more and more sacrifices were needed to feed exceptionalism, from Gordon at Khartoum to Scott in the Antarctic and the necessary deaths of the First World War.

In Wales we have our own example of the British triumph/sacrifice nexus, Sir Thomas Picton. Picton, born in Haverfordwest in 1758, bought an army commission, eventually became one of Wellington’s most trusted generals, and was killed in the fighting at Waterloo on 18 June 1815. After his death a great machine of commemoration cranked into action. In that Valhalla of Empire, St Paul’s Cathedral, Parliament decreed an extravagant monumental sculpture, designed by the Irish sculptor Sebastian Gahagan, complete with bust and full-length figures of a male angel (or Fame), a female angel (or Victory), Roman general in full armour (Picton deified), and lion.

In Carmarthen John Nash was commissioned to design an elaborate monument on the western edge of the town, funded by public subscription, with a grant of a hundred guineas from the King. Completed in 1828, it featured a statue of Picton carved by E.H. Baily, placed atop a Doric column, and a relief frieze on the base showing the death of Picton in the battle.

The frieze, made of ‘Roman concrete’, soon crumbled in the west Wales rain, and Baily had to re-carve it. The fragments that survive of this second version, never installed on the monument, are now in the Carmarthenshire Museum in Abergwili. This frieze is of high quality – its carving is rhythmically energetic but also expressive of the bloodiness of the conflict.

Picton this and Picton that sprang up everywhere. He even gave his name to a town in New Zealand, where the ferry leaves the South Island for Wellington, and another in Ontario, Canada. Over the years, roads, pubs, barracks, ships, beers and even schools (Sir Thomas Picton School in Haverfordwest, closed in 2018) were named after him. This onomastic flood reached its height in 1916, when David Lloyd George unveiled in Cardiff City Hall a new full-length marble statue of Picton. This work, carved by Thomas Mewburn Crook, joined Llywelyn ap Gruffudd and Owain Glyndŵr in Wales’s own Valhalla of national heroes. There could be no better time to enlist the name of Picton into the heroism and self-sacrifice on the First World War: Lloyd George was Minister of Munitions in the War Cabinet, and would soon be Prime Minister.

Despite all this, Picton made an awkward hero. It was no secret, during his lifetime, that he had another side to his character to the bravery of his military exploits. Wellington himself called him a ‘rough foul-mouthed devil’, and he had a well-deserved reputation for severity and cruelty. In 1797 he was put in military charge of Trinidad, newly taken from the Spanish. The island was home to around 10,000 slaves and was also a refuge for runaway slaves and deserting soldiers. With a small military force he enforced order with extreme brutality. Port of Spain’s waterfront became the scene of frequent executions without trial, and its gaol saw ‘flogging, branding, ear-clipping, and the staking out of reprobates in the infamous cachots brûlants’. Picton devised his own harsh slave code, and profited personally from the slave trade.

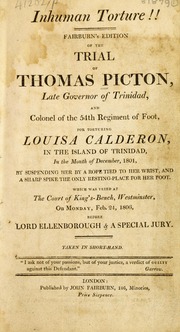

No doubt his methods would have passed unnoticed in London. But he made the mistake of alienating William Fullarton, a young commissioner sent to administer Trinidad. Fullarton, outraged by Picton’s actions and in search of a way of attacking him, pressed criminal charges against him for torturing a Trinidadian woman, Luisa Calderon. In court Picton was found guilty, though he was never sentenced, and in a re-trial he was later partly exonerated. Rehabilitated, he went on to command forces in the Peninsular War, where he was notably careless of human life, losing almost a third of all allied men in one battle.

In 2011 – years before the Rhodes must Fall campaign in 2015 to remove the statue of Cecil Rhodes from Oriel College, Oxford – a solicitor, Kate Williams, drew attention to Picton’s crimes and demanded that Carmarthen Council should remove the portrait of him – one of several painted by the Irish artist Martin Archer Shee – displayed in the part of the Guildhall then used as a courtroom. She was quoted as saying, ‘After hearing that he was alleged to have tortured a slave girl I felt that it was inappropriate to have his picture in a modern court of law where we are supposed to represent the principles of equality and justice for all. I accept that he is a person of note from this area but put him in a museum. I think people might misread the prominence of the picture as saying he has done something worthwhile to contribute towards justice which really isn’t the case.’

Needless to say, the Daily Mail scoffed at this argument, and the Guardian’s art critic Jonathan Jones, ignoring the fact that Kate Williams had not advocated hiding the painting from public view, also weighed in:

… portraiture is a window on the past, warts and all. Villains also deserve their place in the gallery, or in this case, their long day in court. If you applied this censorious logic, you would also have to purge museums of every Gainsborough painting that can be connected with slave-owners.

Ann Dorsett, then the curator of Carmarthenshire Museum, was reported as saying, ‘I think it would be a shame to move it from its original home … I think we have to accept Picton warts and all and not judge him by today’s standards’.

What should we make of this debate? We can set aside the argument that Picton’s actions in Trinidad were unexceptional during the period, and therefore that he should not be judged ‘by twenty-first century standards’. It’s clear that even at the time Picton’s methods were thought to be extreme. Fullarton’s court case excited much attention at the time, and its proceedings were published in more than one book. Much stronger is the argument that we should all be given the chance to see and make our own minds about powerful historical people whose behaviour, at any time, would have been judge reprehensible, rather than allow others to conceal them from view. Most historians, I’m sure, would be comfortable with this approach.

But maybe the matter is not quite as simple as it sounds. For one thing, a ‘display all’ policy for commemorative objects throws a heavy responsibility on their curators, as well as teachers, historians and others, to help viewers understand the complexities of the people – almost invariably people of power – being commemorated. We do need to be informed about the full history and character of someone like Picton in order to make full sense of his portrait. Otherwise we’re all too likely to take the presented image as the truthful image, to be blind to cruelty and injustice. Portraits are painted for a purpose, and that purpose is seldom, if ever, dispassionate or objective. As Jonathan Jones says, ‘Deep in our heritage lies the notion that a portrait is a monument to a hero or a worthy ancestor. To portray is to honour.’ Effective interrogation of a portrait inevitably means questioning its assumptions, and across centuries of history we need help to do so.

As Brexit reminds us, a failure to confront truths about our past can have dire consequences for us. As Tyler Stiem writes, in his study of the ‘statue wars’ in South Africa and elsewhere,

[Many people] have arrived at the … conclusion [that] the situation is bad today because we have strayed too far from the way things used to be. The nostalgia of Brexit and Make America Great Again is exactly an appeal to the consoling idea (for some white people) that the moral failures of the past are, in fact, the triumphs we once thought they were. Statues, buildings and street signs have become flashpoints because they embody the tension between these two worldviews.

A second qualification to the ‘hang them all’ argument is that the ideological content of some memorials can be so raw, so live and so explosive to people that they can be forgiven for wanting to remove or even destroy them.

This is most obvious with recent history. How many of us would have cared to stand in the way of people tearing down statues of Stalin in Budapest in 1956 or of Sadaam Hussain in Baghdad in 2003, and tried to persuade them to behave more reasonably in the interests of open debate? These objects were detested almost as much as the subjects they represented. But even older memorials have the capacity to carry inside them, and so arouse, passionate contemporary, especially when ancient wrongs, like slavery and segregation, have still not been expiated. A good example is the crop of grandiose monuments to figures like Robert E. Lee and other Confederate leaders throughout the American South, symbols of continuing oppression and discrimination (admittedly some of these statues are surprisingly recent). The ‘Rhodes must Fall’ campaign in Cape Town in 2015 was a much more serious and passionate affair than its Oxford counterpart.

A footnote. Our friend Sir Thomas Picton has another memorial in Carmarthenshire, which I was lucky enough to be introduced to by a friend this week. Iscoed is a country house in the classical style near Ferryside with a long, oblique view across fields and woods of the broad Tywi estuary. It was built in 1772 for Sir William Mansel, but was still unfinished when Picton, recuperating from injuries sustained in Spain, decided to buy the house and estate in 1812 for £30,000. His intention was to spend his retirement there, but after Napoleon escaped from exile on Elba Wellington called him back. By June 1815 he was in Belgium, and never saw Iscoed again.

Today the main building at Iscoed, approached via a long gloomy lane overhung by trees, is no more than a plain roofless box. It was designed, probably, by Anthony Keck and was built of brick (from Bridgewater, transported by Thomas Keymer of Kidwelly), and had two brick wings. The south wing is still inhabited in part, but the rest of the buildings are in ruin.

Visiting ruins is often the best way of putting the works of powerful and dominant men into the proper perspective of time.

Leave a Reply