You can’t wander far in south and mid-Wales in the early years of the nineteenth century without coming across the name of Benjamin Heath Malkin. The second edition of his book The scenery, antiquities and biography of south Wales, published in two volumes in 1807, was described by the historian R.T. Jenkins as ‘by far the best of the old travel-books on south Wales – acute and amusing in its observation, usually tolerant in its judgements, with a substantial knowledge of Welsh history and (up to a point) of Welsh literature’.

Malkin’s book, which originated in a tour of south Wales in 1803, is always readable, especially for his often original opinions. Here’s his rationale for supporting the Welsh language in Cardiganshire (his view of its residents as ‘miserable mountaineers’ is maybe less than ‘tolerant’):

[The language] is, through the greater part of this county, almost without exception Welsh. This separation is, in the opinion of some, sedulously to be maintained. A community of language with the English would tend to render these simple, and, if they were acquainted with any thing better, miserable mountaineers, discontented with their dreary quarters and hard fare, and disposed to emigrate in quest of high wages, and what are generally termed the comforts of life. But while they are insulated by a tongue of their own, they are tied down by a peculiar necessity to the place that gave them birth, and their desertion of a post, to which nature and providence have assigned them, is not to be apprehended. It is so far certain, that their gains are small, their mode of living coarse in the extreme, their habitations squalid, and their very existence dependent on the good pleasure of their thinly scattered employers.

Malkin was born in London – later he became the first Professor of History in the University of London. In about 1794 he married Charlotte Williams, the daughter of the curate of Cowbridge, and he lived from about 1830 until his death in 1842 in the Old Hall in the town (he’s commemorated by an inscription in the church).

Outside Wales Malkin is better known for another of his books, A father’s memoirs of his child (1806), and for his friendship with William Blake. The two are linked. The book was published after his son, Thomas Williams Malkin, died aged six in 1802. Thomas was a child prodigy. His father insists that he has not interfered in Thomas’s self-education: ‘at this time [aged four], he could read, without hesitation, any English book. He could now spell any words, of whatever length they might be, or however discordant the orthography from the pronunciation. He knew the Greek alphabet, and could read most Greek words, not exceeding four syllables.’

Malkin dedicates his book to Thomas Johnes, the famous owner of Hafod, and recalls how his visit in 1803 sparked the idea of a travel book:

When I first traversed your mountains, it was without the most distant thought of engaging a set of readers as the companions or followers of my journey. The fever of authorship never preyed upon my better sense, till your magic creation in the wilds of Cardiganshire gave vent to its fury. The singular combinations of beauty and grandeur, the contrast of wildness and improvement, to be found within the circuit of your estate, first disposed me to extend my excursion through the remaining counties of South Wales, and to attempt a description of its picturesque scenes.

He goes on to explain his connection with Blake. Malkin had met Blake in London in the early 1790s, and shared his radical political views. The two became friends, and Malkin did more than most to promote Blake’s work. This passage is the earliest account that exists of Blake’s early life, and ends with transcriptions of some of the poems from Songs of innocence and Songs of experience: these first drew the attention of a wider public to Blake’s poetry.

One of Thomas’s preoccupations was inventing an imaginary world, which he called Allestone, with the help of his own maps and drawings. His father quotes Blake as praising both map and sketches: ‘All his efforts prove this little boy to have had that greatest of all blessings, a strong imagination, a clear idea, and a determinate vision of things in his own mind.’ Benjamin reproduces many of his son’s letters, poems and other writings – and his detailed map of ‘a visionary country, called Allestone, which was so strongly impressed on his own mind, as to enable him to convey an intelligible and lively transcript of it in description’.

Of this delightful territory he considered himself as king. He had formed the project of writing its history, and had executed the plan in detached parts. Neither did his ingenuity stop here; for he drew a map of the country, giving names of his own invention to the principal mountains, rivers, cities, seaports, villages, and trading towns. As learning was uniformly the object of his highest respect, and principal attention, he endowed his kingdom most liberally with universities. The professors, whose offices were some of them mentioned incidentally in a preceding letter, were appointed by name; and numerous statutes were enacted, which for their grave promulgation would scarcely have been disowned by more ancient and venerable founders.

The map of Allestone, in whatever light it is viewed, is a very remarkable production. Crowded as it is with names, some absurd, but others ingenious and appropriate, it evinces an uncommon fertility of invention. The drawing is executed with care, and the propriety of the design made happily to coincide with its whimsical and capricious humour… The country is an island, and therefore the better calculated for the scene of the transactions he has assigned to it. The rivers, for the most part, rise in such situations, and flow in such directions, as they would in reality assume. Their course is marked out with reference to the position of principal towns, and other objects of general convenience. The map is therefore not so much to be looked at for the neatness of its appearance, and the symmetry of its proportions; but as an exercise of the mind comparing the propriety of its own nascent ideas and inventions, with the performances of adult artists, founded on observation and authority.

Benjamin quotes letters from Thomas that describe in detail the people of Allestone, stories about them, a list of their personal names, customs and historical events – elements not copied from others but ‘borrowed principally from the natural workings of an ingenuous mind’.

There follows a lengthy account of Thomas’s illness and death, and a brief conclusion: ‘his star has faded from among the glories of this world: yet we believe that he still must occupy his sphere of usefulness in the system of creation.’ Thomas’s death clearly had a profound effect on his father, who seems almost to have felt little choice but to commemorate and publish his son’s life and early achievements. His writing style is of its period, ornate and extended, but his theme and his apparently self-therapeutic motivation seem to fit easily into the ‘memoir of loss’ genre of the 21st century.

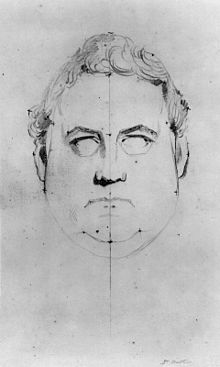

Blake contributed two images to A father’s memoirs of his child. For the frontispiece he designed a portrait of Thomas (it was engraved by Robert Cromek), surrounded by an angel taking the hand of the child from his mother. He also printed Thomas’s map, as a fold-out sheet. Its full title is ‘A corrected and revised map of the county of Allestone, from the best authorities, by Thomas Williams Malkin, done 1 October 1801’. Allestone is an island, full of bays and inlets, and fed by numerous rivers, like the Glams, Rugg and Malleb. The interior abounds in villages and hamlets, with names like Gob, Nubble, Pshibb and Bobble, and off the coast are many small islands, like Lucky Island, Nobblede Island and Chamborry Island. Thomas was as humorous as he was inventive, and maybe Blake smiled as he reproduced his map.

Map-making, you might think, is not an activity that would have appealed naturally to Blake, who detested the Newtonian, rationalist mission to pin down the world with compass and dividers. On the other hand, it’s not hard to see how he might have welcomed the chance to explore Thomas’s ‘exercise of the mind’ or landscape of the imagination – the kind of universe he inhabited himself in so much of his poetry and art. Rachel Hewitt, in her history of the Ordnance Survey, Map of a nation, notes that ‘his map was devoid of the type of geometry that characterised maps like the Ordnance Survey’s’.

The Huntington in San Marino, California is currently showing an exhibition of imaginary literary maps, ‘Mapping fiction’. I’m not sure whether it includes the Malkin/Blake map of Allestone, but it certainly deserves a place alongside maps illustrating works by Bunyan, Robert Louis Stevenson, Faulkner and Joyce.

Note: The only other map engraved by William Blake, strangely enough, is a plan of part of Thomas Johnes’s Hafod estate, in An attempt to describe Hafod (1796) by George Cumberland.

Leave a Reply