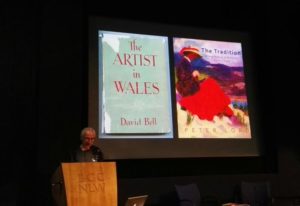

In front of me is a copy of The artist in Wales, the first book to attempt a full conspectus of art in Wales, past and present. It was written in 1957 by David Bell, when he was Curator of the Glynn Vivian Art Gallery. It’s a drab volume, even taking into account the austere times. The jacket is plain and there are just thirteen plates of murky black and white illustrations. In its less than 200 pages the text trundles mechanically through different art forms – architecture, painting, printing and pottery. It gives almost as much space to art made by outsiders coming to Wales as to home-based art, and it looks to the future and not to the past for a flourishing of visual art in Wales.

In front of me is a copy of The artist in Wales, the first book to attempt a full conspectus of art in Wales, past and present. It was written in 1957 by David Bell, when he was Curator of the Glynn Vivian Art Gallery. It’s a drab volume, even taking into account the austere times. The jacket is plain and there are just thirteen plates of murky black and white illustrations. In its less than 200 pages the text trundles mechanically through different art forms – architecture, painting, printing and pottery. It gives almost as much space to art made by outsiders coming to Wales as to home-based art, and it looks to the future and not to the past for a flourishing of visual art in Wales.

Next I turn to The tradition. This is a weighty, large-format book, of almost 400 pages and beautifully printed on heavy paper. Its 400 illustrations, many of them full-page, are superbly reproduced in colour. Its text celebrates the many and varied achievements of artists in Wales through history. The approach is sensibly chronological and a huge array of evidence, much of it from manuscript sources, supports the arguments.

If you had to point to a single explanation for the enormous differences between these two books – there have been very few general histories of Welsh art published in the interim – it would be the achievements of the author of the second. Over the last twenty five years, almost single-handedly, Peter Lord has transformed a collection of poorly understood evidence of art created in Wales, and lazy theoretical assumptions about it, into a discipline in its own right, equipped with analytical frameworks and supported by an accumulating body of knowledge. The climax of this effort was The visual culture of Wales (VCW), three large volumes published by the University of Wales Press between 1998 and 2003 as the culmination of a major project at Aberystwyth’s Centre for Advanced Welsh and Celtic Studies.

If you had to point to a single explanation for the enormous differences between these two books – there have been very few general histories of Welsh art published in the interim – it would be the achievements of the author of the second. Over the last twenty five years, almost single-handedly, Peter Lord has transformed a collection of poorly understood evidence of art created in Wales, and lazy theoretical assumptions about it, into a discipline in its own right, equipped with analytical frameworks and supported by an accumulating body of knowledge. The climax of this effort was The visual culture of Wales (VCW), three large volumes published by the University of Wales Press between 1998 and 2003 as the culmination of a major project at Aberystwyth’s Centre for Advanced Welsh and Celtic Studies.

VCW was academic in intent and all three volumes have been out of print for years. The Tradition aims to crystallise the essence of their content while aiming at a wider readership – in Lord’s words, ‘everyone with an interest in Wales and in art’. It isn’t, though, a simple distillation of its predecessors. It adds many new works and it references many new studies that have appeared since. More seriously, the time span of The tradition departs from that of VCW. It begins in the year 1400, avoiding the early and medieval periods covered in detail in the Medieval vision volume of VCW. In his introduction Lord blames the restrictions imposed by a single physical volume. But I wonder whether he’s willing to sacrifice the earlier periods in part because their works shared common European styles and were yet to develop the distinctively Welsh features that are his true interest. Lord chooses the year 1400 as a starting point because he feels that Renaissance ideas and modes took hold in Wales earlier that he had previously thought, although the text and images here hardly bear this out, and we’re ushered swiftly into the Tudor period.

VCW was academic in intent and all three volumes have been out of print for years. The Tradition aims to crystallise the essence of their content while aiming at a wider readership – in Lord’s words, ‘everyone with an interest in Wales and in art’. It isn’t, though, a simple distillation of its predecessors. It adds many new works and it references many new studies that have appeared since. More seriously, the time span of The tradition departs from that of VCW. It begins in the year 1400, avoiding the early and medieval periods covered in detail in the Medieval vision volume of VCW. In his introduction Lord blames the restrictions imposed by a single physical volume. But I wonder whether he’s willing to sacrifice the earlier periods in part because their works shared common European styles and were yet to develop the distinctively Welsh features that are his true interest. Lord chooses the year 1400 as a starting point because he feels that Renaissance ideas and modes took hold in Wales earlier that he had previously thought, although the text and images here hardly bear this out, and we’re ushered swiftly into the Tudor period.

At the other end of the time spectrum Lord’s cut-off point is 1990. This he explains by his over-closeness to the artists and art in the last 25 years. You do sense, though, that Lord finds it hard to do justice to the quantity and diversity of art being produced well before 1990. The challenge is obvious to anyone taking a look at Peter Jones and Isabel Hitchman’s massive dictionary of post-war Welsh artists.

On the whole, though, Lord weaves the confident path of one who’s travelled the main roads and byways many times. The narrative flows smoothly across the centuries. Anyone familiar with his work will recognise points at which the pace slows to do justice to his particular interests: the early portraitists, the ‘artisan’ painters, the nonconformist imagination, the Betws-y-Coed colonists, surfers of the ‘first wave’ of national consciousness between 1880 and 1914, responses to the new communities of iron and coal, the private patrons, especially Winifred Coombe-Tennant, and, during and after World War II, the support of the state. There are so many of these episodes that you can only marvel that one scholar has been responsible for excavating and analysing them all.

The tradition has been expertly edited, though a few mistakes remain. John Sell Cotman never visited Swansea, as we’re told on p.137, and some of the attributions are over-definite: is it certain that John Petherick painted the remarkable ‘Egyptian’ furnaces at Rhymney (p.207)? A bibliography would have been useful. As in VCW, it’s difficult to track down the current locations of the works illustrated. But these are minor flaws. This is a book of high quality, in content and appearance (many congratulations to the publisher, Parthian, and the printer, Gwasg Gomer), and it will hold its own for many years to come.

With The Tradition Lord hammers his final stake into David Bell’s view, born of ignorance as much as of insecurity and servility, that ‘the fine arts have played a negligible part in Welsh life, the applied arts only a rudimentary one’ (The artist in Wales, p.5). His underlying theme is that Welsh artists (and artisans) constantly found their own distinctive tones within the chorus of other voices from across Offa’s Dyke or from the Continent. His preference is always for those who sing most clearly in their native tongue (hence his distaste, for example, for the bland internationalism of the original 56 Group artists). The voices sing in all registers, and Lord’s title The tradition is misleading, since there are in truth as many different traditions as there are artists: outsider artists visiting Wales, gentry-pleasing canvas painters, demotic painters on board, print illustrators, public criers and national awakeners, and unclassifiable experimentalists, true ‘outsider artists’.

In his foreword M. Wynn Thomas justly calls The tradition Peter Lord’s ‘gift to the Welsh people’. Alas, even though its price is very reasonable, it may be beyond the reach of many people in Wales to buy. Any government with enough vision and commitment to the cause of art and creativity would immediately arrange for every household in Wales to receive a copy free. What a gift that would be, and what unforeseen effects it might have! It’s not, I suppose, an announcement we can expect soon. Just as there’s no sign of establishing the long-debated national gallery of art, or of modern art (Edinburgh has four!). On the contrary, the Welsh Government minister responsible for culture, Ken Skates – it seems we can no longer afford a minister dedicated to arts or culture – is rumoured to favour merging two of our few national cultural institutions, the National Library and the National Museum*. Just as Peter Lord triumphantly proclaims the richness and variety of our artistic heritage, the government appears to be suffering from a catastrophic loss of confidence in our future.

*Since this review was written Ken Skates has set up a group to plan a new body called Historic Wales, responsible for the ‘commercial functions’ of the National Museum and CADW. This move would directly undermine the independence of the Museum and its ability to be economically sustainable. The BBC reports that the National Library could also be obliged to join the new body.

Peter Lord, The tradition: a new history of Welsh art, 1400-1990, Cardigan: Parthian, 2016.

Reproduced by kind permission of the editor of Wales Arts Review, where the review originally appeared.

Leave a Reply