If last year was a desperate time in the public world, there were plenty of comforts closer to home. As always, reading was one of them. These days I read more than I have since I was a teenager, with the added advantage that if I find a book unreadable I’m now happy, time and life being short, to leave it unfinished. In no particular order here are some of the (English language) books I did succeed in finishing in 2016.

If last year was a desperate time in the public world, there were plenty of comforts closer to home. As always, reading was one of them. These days I read more than I have since I was a teenager, with the added advantage that if I find a book unreadable I’m now happy, time and life being short, to leave it unfinished. In no particular order here are some of the (English language) books I did succeed in finishing in 2016.

Adam Thorpe, On Silbury Hill

I bought this in August in the excellent Booka bookshop in Oswestry, when the National Eisteddfod was in Meifod, simply because it looked so handsome: a small square shape, sturdy cover and binding, well-designed jacket, lovely Garamond type on good white paper. The publisher is one of my favourites, Little Toller Books of Toller Fratrum in Dorset. As a bonus the content is worth reading: an autobiographical meditation by Adam Thorpe, author of the novel Ulverton, on Silbury Hill, the mysterious prehistoric artificial hill in Wiltshire. The ghost of W.S. Sebald hovers in the background, and the text comes with grainy, captionless archive photographs in the style of the master. One of them shows Professor Richard Atkinson, the excavator of Silbury, who long ago failed to get me to complete a thesis I started.

I bought this in August in the excellent Booka bookshop in Oswestry, when the National Eisteddfod was in Meifod, simply because it looked so handsome: a small square shape, sturdy cover and binding, well-designed jacket, lovely Garamond type on good white paper. The publisher is one of my favourites, Little Toller Books of Toller Fratrum in Dorset. As a bonus the content is worth reading: an autobiographical meditation by Adam Thorpe, author of the novel Ulverton, on Silbury Hill, the mysterious prehistoric artificial hill in Wiltshire. The ghost of W.S. Sebald hovers in the background, and the text comes with grainy, captionless archive photographs in the style of the master. One of them shows Professor Richard Atkinson, the excavator of Silbury, who long ago failed to get me to complete a thesis I started.

Barry Hines, A kestrel for a knave

This should have been a re-read, but to my shame I never read it in the 1960s when it first appeared, even though Barry Hines, who died in March, came from near our south Yorkshire home and I’d seen Ken Loach’s film adaptation as soon as it came out. The story of Billy Casper, a working-class ‘failure’ whose life is irradiated by a passion for a tamed hawk, hasn’t dated in the slightest, and the extinguishing of hope is just as shocking. I found a second-hand copy of the Penguin reprint, with a famous still from Kes on the cover, in the fine Pen’rallt Gallery Bookshop in Machynlleth.

This should have been a re-read, but to my shame I never read it in the 1960s when it first appeared, even though Barry Hines, who died in March, came from near our south Yorkshire home and I’d seen Ken Loach’s film adaptation as soon as it came out. The story of Billy Casper, a working-class ‘failure’ whose life is irradiated by a passion for a tamed hawk, hasn’t dated in the slightest, and the extinguishing of hope is just as shocking. I found a second-hand copy of the Penguin reprint, with a famous still from Kes on the cover, in the fine Pen’rallt Gallery Bookshop in Machynlleth.

Graeme Macrae Burnet, His bloody project

This novel, shortlisted for the Booker Prize, is a psychological and philosophical investigation masquerading as a historical true crime story. Archival accounts ‘document’ the circumstances of a gruesome triple murder committed in a remote hamlet in the Applecross peninsula in 1869. The longest and best section is the murderer’s recollection of the events leading to his self-confessed acts. His narrative, brilliantly ‘authentic’, gradually intensifies the grim social claustrophobia and the psychic oppression, until only one solution seems possible. Mental note: must revisit Applecross (walked up Bealach na Bà in about 1968 or 1969).

This novel, shortlisted for the Booker Prize, is a psychological and philosophical investigation masquerading as a historical true crime story. Archival accounts ‘document’ the circumstances of a gruesome triple murder committed in a remote hamlet in the Applecross peninsula in 1869. The longest and best section is the murderer’s recollection of the events leading to his self-confessed acts. His narrative, brilliantly ‘authentic’, gradually intensifies the grim social claustrophobia and the psychic oppression, until only one solution seems possible. Mental note: must revisit Applecross (walked up Bealach na Bà in about 1968 or 1969).

Francesca Rhydderch, The rice paper diaries

Anyone who’s haunted by a reading of J.G. Ballard’s Empire of the sun, based on his childhood experience of the wartime Japanese occupation of Shanghai, will take immediately to this novel, set mainly in Hong Kong before and after its capture by the Japanese in 1941. An expatriate child’s view of horrendous adult events is again a central theme, but there are other viewpoints too, including a particularly touching story of a Chinese woman. This is literary archaeology taken a long way beyond historical trowelling by high imagination and style.

Anyone who’s haunted by a reading of J.G. Ballard’s Empire of the sun, based on his childhood experience of the wartime Japanese occupation of Shanghai, will take immediately to this novel, set mainly in Hong Kong before and after its capture by the Japanese in 1941. An expatriate child’s view of horrendous adult events is again a central theme, but there are other viewpoints too, including a particularly touching story of a Chinese woman. This is literary archaeology taken a long way beyond historical trowelling by high imagination and style.

Dominick Tyler, Uncommon ground: a word-lover’s guide to the British landscape

An unusual book, picked up for £1 in Tenovus in Mumbles: a collection of very short essays on ‘regional’ words for landscape features, opposite striking colour photos by the author. For once British means British, and Ireland, Scotland and Wales are all well represented. Some of the words: swag, machair, gwisgo’i gap, nurse log, tombolo, zawn. Tyler has polished his words as carefully as he’s perfected his pictures: I’ll try to copy some of his ways of playing variations on a theme.

An unusual book, picked up for £1 in Tenovus in Mumbles: a collection of very short essays on ‘regional’ words for landscape features, opposite striking colour photos by the author. For once British means British, and Ireland, Scotland and Wales are all well represented. Some of the words: swag, machair, gwisgo’i gap, nurse log, tombolo, zawn. Tyler has polished his words as carefully as he’s perfected his pictures: I’ll try to copy some of his ways of playing variations on a theme.

Francis Spufford, Golden Hill

Another historical voice of astounding plausibility. This one belongs to an English visitor to pre-revolutionary New York. He’s on a special mission, only revealed at the end; the mystery puzzles and infuriates his American hosts. This is Spufford’s first novel, but far from being his first book. His first is a classic, about the strange relationship of the British with the polar regions, I may be some time. The plot of Golden Hill meanders, but the style is full of delights and vivid fresh imagery on almost every page. Mental note: must read Colson Whitehead’s The underground railroad in 2017.

Another historical voice of astounding plausibility. This one belongs to an English visitor to pre-revolutionary New York. He’s on a special mission, only revealed at the end; the mystery puzzles and infuriates his American hosts. This is Spufford’s first novel, but far from being his first book. His first is a classic, about the strange relationship of the British with the polar regions, I may be some time. The plot of Golden Hill meanders, but the style is full of delights and vivid fresh imagery on almost every page. Mental note: must read Colson Whitehead’s The underground railroad in 2017.

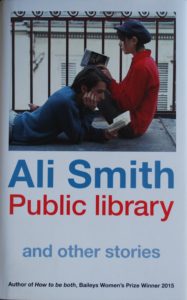

Ali Smith, Public library

A passionate defence of the British public library, now as threatened as the tiger and the polar bear, but once just as powerful. It takes an unusual form: short stories, all in some way about books and what they do for us, interspersed with quotations collected by Ali Smith from various ordinary people testifying to the influence of libraries on their lives. The first piece says it all: called Library, it tells of a visit to a building labelled ‘Library’ that turns out to be an expensive private members club.

A passionate defence of the British public library, now as threatened as the tiger and the polar bear, but once just as powerful. It takes an unusual form: short stories, all in some way about books and what they do for us, interspersed with quotations collected by Ali Smith from various ordinary people testifying to the influence of libraries on their lives. The first piece says it all: called Library, it tells of a visit to a building labelled ‘Library’ that turns out to be an expensive private members club.

Hugh Stephenson, Secrets of the setters

I won this in a Guardian Saturday crossword competition. Quite why they think this book, written by Hugh Stephenson, the paper’s crossword editor, would be anything other than a completely redundant reward for a regular solver is beyond me. But it’s a witty read, especially the section on crossword history, with its pen portraits of legendary setters like Torquemada, Ximenes and Araucaria.

I won this in a Guardian Saturday crossword competition. Quite why they think this book, written by Hugh Stephenson, the paper’s crossword editor, would be anything other than a completely redundant reward for a regular solver is beyond me. But it’s a witty read, especially the section on crossword history, with its pen portraits of legendary setters like Torquemada, Ximenes and Araucaria.

Diana Athill, Stet: an editor’s life

Diana Athill is famous for being very old but increasingly productive in her writing (she’d belong comfortably in Edward Said’s list in On late style). This is the book that made her name, fifty years after she began in publishing, mainly as an editor. Her great publishing mentor was André Deutsch, a Hungarian emigré. Her affectionate but honest portrait of him in the first half of the book is followed by pictures in the second of many of ‘her’ authors, like Jean Rhys and V.S. Naipal. Publishing is now dominated by big multinationals, but smaller firms, like Little Toller, still survive and Athill’s world has not completely disappeared, I suspect. Another book picked up for a song in a Mumbles charity shop.

Diana Athill is famous for being very old but increasingly productive in her writing (she’d belong comfortably in Edward Said’s list in On late style). This is the book that made her name, fifty years after she began in publishing, mainly as an editor. Her great publishing mentor was André Deutsch, a Hungarian emigré. Her affectionate but honest portrait of him in the first half of the book is followed by pictures in the second of many of ‘her’ authors, like Jean Rhys and V.S. Naipal. Publishing is now dominated by big multinationals, but smaller firms, like Little Toller, still survive and Athill’s world has not completely disappeared, I suspect. Another book picked up for a song in a Mumbles charity shop.

Emily Berry, Anne Carson and Sophie Collins, If I’m scared we can’t win (Penguin modern poets, 1)

This year Penguin relaunched its old modern poets series. The format is the same, with selections from the work of three living poets. Alas, though, the plain cover can’t compare with the bold illustrations of the earlier series. I’m not sure the latter would have featured three women together, but the effect here is wonderful: three very different voices that share a colloquial tone and a liking for experimental form. The oldest of the three, and the outstanding one for my money, is the Canadian Anne Carson, who uses themes from her day job as a classics professor to powerful effect.

This year Penguin relaunched its old modern poets series. The format is the same, with selections from the work of three living poets. Alas, though, the plain cover can’t compare with the bold illustrations of the earlier series. I’m not sure the latter would have featured three women together, but the effect here is wonderful: three very different voices that share a colloquial tone and a liking for experimental form. The oldest of the three, and the outstanding one for my money, is the Canadian Anne Carson, who uses themes from her day job as a classics professor to powerful effect.

Helen Simpson, Four bare legs in a bed

Helen Simpson writes almost exclusively about women, usually in the company of women. That’s no doubt why she’s not regarded as the best of our home-grown short story writers – as she is. You have to wait several years for a new collection to appear. In the meantime her women have aged a bit more since the previous volume. I’ve bought each as it came out, with the one exception, the very first, Four bare legs in a bed (1990). My heart leapt up when I discovered a battered copy, again in a Mumbles charity shop. The stories are sharp anatomies of middle class life, but the satire almost always carries an undertow of melancholia.

Helen Simpson writes almost exclusively about women, usually in the company of women. That’s no doubt why she’s not regarded as the best of our home-grown short story writers – as she is. You have to wait several years for a new collection to appear. In the meantime her women have aged a bit more since the previous volume. I’ve bought each as it came out, with the one exception, the very first, Four bare legs in a bed (1990). My heart leapt up when I discovered a battered copy, again in a Mumbles charity shop. The stories are sharp anatomies of middle class life, but the satire almost always carries an undertow of melancholia.

William Shakespeare, Macbeth

Another shamefully-never-before-read text. In October we went to see an energetic Volcano production featuring just two characters, Macbeth (Alex Harries) and Lady Macbeth (Maire Phillips). Back home I got my old Arden version from the shelf, started with the witches and one bloody thing led to another. It was great to re-encounter Macbeth’s lines

Another shamefully-never-before-read text. In October we went to see an energetic Volcano production featuring just two characters, Macbeth (Alex Harries) and Lady Macbeth (Maire Phillips). Back home I got my old Arden version from the shelf, started with the witches and one bloody thing led to another. It was great to re-encounter Macbeth’s lines

… No, this my hand will rather

The multitudinous seas incarnadine

Making the green one red.

In secondary school we had an English teacher – he was really an RE teacher, but filled in with English – who would make us learn what he called ‘curts’, or small snatches of verse, to be repeated back to him in the next lesson. This was one of them, and it’s stayed with me ever since, an example of latinate and anglo-saxon vocabulary clashing to momentous effect.

Leave a Reply