2021 was another big reading year, thanks to continuing Covid. Some books, especially fiction, arrived thanks to our resuscitated book club – almost all were titles I’d not have thought of taking off the shelf myself, so they were doubly welcome. But here are some 2021 books read out of personal necessity, curiosity or whim.

The Wye Valley Walk Partnership, Walking the Wye Valley Walk

This one wins the prize for the best thumbed book of the year – and we’re only half way through both Walk and book. Its text is anonymous: there’s not a single name mentioned as author. As with most footpath guides it’s easy to pull holes in this one. Thanks to its ambiguous instructions we went wrong even before we’d left Chepstow. The maps included aren’t detailed enough, as usual with guides published by Cicerone, and, like John Ogilby’s strip maps of 1675, they only include land immediately adjacent to the Walk, so we found we needed to use the book maps in combination with the Ordnance Survey app (Explorer scale). But as a walker you wouldn’t want to be without this guide, for its directions, background, photos and very occasional humour. Several times on our walks C and I have wondered whether we couldn’t write better footpath guides ourselves. But I suspect it’s a much harder task than it seems. Still at No. 1 in our joint league table of guides, by the way, is Brian John’s Pembrokeshire Coast Path, for its accuracy, helpfulness and geological enthusiasm.

Michael Innes, Death at the President’s lodging

I’ve made a small contribution to the literature on violent (fictional) academic death, so when I saw a second-hand copy of this crime novel in the Tenovus shop I knew I couldn’t leave without it. Michael Innes was the pseudonym of J.I.M. Stewart, an Oxford English don between 1949 and 1973. He wrote many academic books, and some ‘straight’ novels, but he’s best known for his Inspector John Appleby detective novels, of which Death in the President’s lodging (1935) was the first. The President of St Anthony’s College has been shot dead. In what’s a variation on the ‘sealed room’ puzzle, the only plausible suspects are the College fellows. It doesn’t come as a surprise to discover that they’re so full of bitterness, envy and academic spite that any one of them could have pulled the trigger. As with many ‘classic age’ crime novels, Innes’s plotting is satisfyingly complex, though he neglects motivation, psychology and character, and his orotund prose is strongly of its period and class. In a nice pre-postmodern touch, one the fellows/suspects turns out to be a writer of detective fiction. Another, not the culprit, is named Empson. I wonder what William Empson, who was already a well-known poet and critic by 1935, would have made of that? Perhaps he was in on the case.

J.A. Hazeley and J.P. Morris, How it works: the grandparent

By far the most painful read of the year, this is another spoof Ladybird book. As usual the pictures take us back to another world, the cosy middle-class 1950s (or earlier), while the text, ferociously contemporary, subverts the images. I often found myself laughing with the text. As a non-gardener I can chuckle happily at: ‘Grandparents spend a lot of time in the garden, making everything tidy and pretty to look at while they are doing the garden.’ Similarly with the post-retirement addiction to home improvement: ‘Linda and Derek have decorated their hallway. Now they plan to decorate the front room, the sitting room, the bedrooms, the garage and the roof. Then, next month, they will start on the hallway again.’ But this one is far too close to reality to feel comfortable with: ‘Before he retired, Ted worked at a nuclear power station, monitoring the pressure of the boilers and the temperatures of the zirconium alloy control rods in the reactor core. Now he does not know how to set the correct aspect ratio on his television set. He leaves that to his nine-year-old granddaughter.’ Ow!

M. Wynn Thomas, The history of Wales in twelve poems

The University of Wales Press doesn’t often venture out of academic publishing these days, but this book proves that when it does it can still produce excellent books for a general audience. What struck me most about it, before reading a single word, was its handsomeness. It’s brilliantly and cleanly designed, by Olwen Fowler. Dusk jacket, paper, binding, typeface, illustrations – all are of the highest quality. It’s a short book, just over 100 pages. This sets very tight limits on the length of the historical narrative, chopped up into twelve mini-chapters, and on the number of poems. M. Wyn Thomas packs a lot into a short space. His style is elegant and his insights come thick and fast, especially in the later chapters. Women and ethnic minorities are a bit more prominent than in conventional histories of Wales. Each chapter takes as its starting point the immediately preceding poem. The poems (four are by women) are a good mix of the familiar – ‘The Gododdin’, ‘Trafferth mewn tafarn’ and ‘Fern Hill’ – and the less well-known. It’s good to see Gwenallt’s ‘Y meirwon’, surely one of the most powerful modern poems written in Wales, and poems by Gillian Clarke and Menna Elfyn. Finally, scattered throughout the book are woodcuts, stylised but highly expressive, by Ruth Jên Evans. M. Wynn Thomas’s aim in the book is ‘to make my Wales just a little easier to see’.

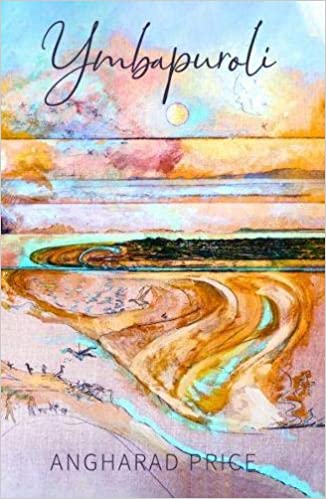

Angharad Price, Ymbapuroli

Most agree that Angharad Price’s novel of 2002, O! Tyn y gorchudd, translated as The life of Rebecca Jones, is one of the outstanding works of fiction produced in Welsh in recent decades. She’s also a distinguished researcher, with a special interest in T.H. Parry-Williams, and her lengthy study of his crucial time in Germany before the First World War appeared in 2013. As well as being a poet and scholar Parry-Williams published a good number of essays, on all kinds of subject, large and small, that are read today almost as much as his poetry. Angharad Price’s Ymbapuroli is a direct descendant of the THPW essay-writing tradition. There are twelve essays in the collection, some previously published in periodicals like O’r Pedwar Gwynt, others not. The subjects range widely, from memories of her grandparents and father, Holyhead, and spoken language, to Jan Morris, Karl Marx and toilet paper (the title, Ymbapuroli, is apt, since paper of different sorts keeps reappearing as a theme throughout). It’s not just the subjects that vary so much. Angharad Price deals with them by varying her forms: they include diary, collage and translation. She’s a pliant, subtle and resonant writer. As soon as you’ve finished a piece you feel like going back to the beginning of it, to try to work out how she did it.

Sathnam Sanghera, Empireland

Sometimes I think the best way of countering imperial nostalgia and global power delusion in this country, so avidly exploited by our current rulers, would be to teach all schoolchildren that the term ‘Great Britain’ has nothing to do with majesty and the ability to lord it over other nations: it was just a convenient way of distinguishing ‘big Britain’ (our small island) from ‘little Britain’ (Brittany). Sathnam Sanghera sets himself a more practical, and ambitious aim: to explain the deep roots of our imperial self-deception. His sub-title reads, ‘how imperialism has shaped modern Britain’. Sanghera’s a journalist, not a professional historian, but his knowledge of the history and grasp of historical sources – the bibliography and notes take up nearly 100 pages – are impressive. He writes beautifully, and isn’t afraid to write from a personal perspective (chapter 2 is titled ‘Imperialism and me’.) He discusses all the key features of the nature of the British empire, its aggression, exploitation and racism, but with nuance and without adopting a ‘charge-sheet’ way of approaching them. He ends with a mention of how Manchester students covered a mural of Kipling’s ‘If’ with Maya Angelou’s ‘Still I rise’ – but without obliterating Kipling’s words: ‘it was less a statement’, he says, ‘than an invitation to ask questions’.

Duncan Minshull (ed.), Sauntering: writers walk Europe

Another walking book, in a year dominated by research on walking. Duncan Minshull is a radio producer who’s published several books on the subject. Sauntering is a companion to his earlier anthology Beneath my feet. That book covered many obvious sources, including Hazlitt, Dickens, Robert Louis Stevenson, Virginia Woolf and Rebecca Solnit, as well as some less so, like the indoor walker Xavier de Maistre. This new book, handsomely produced by Notting Hill Editions, confines itself to Europe, but is just as diverse in its choice of 54 pieces. It starts with Patrick Leigh Fermor and ends with Nicholas Luard, and on the way we meet, toiling up Mont Ventoux, Petrarch, whom Minshull claims was the first pedestrian writer, in 1350; Fridtjof Nansen, in Arctic wastes, dreaming about a childhood walk with his father; and Werner Herzog on his bizzare winter journey on foot across Europe to prevent Lotte Eisner from dying. Heinrich Heine recalls the daily walks of Immanuel Kant. At exactly half past three each day Kant left his house, ‘went to the lime-tree avenue, which is still called the Philosopher’s Walk in memory of him’, and walked exactly eight times up and down whatever the weather. The funniest, and most depressing, piece is this, which Minshull labels as ‘Fragment, 1796’: ‘I encountered a Mr Hackman, an Englishman, who had been walking the length and breadth of Europe for several years. I enquired of him what were his chief observations. He replied gruffly: ‘I never look up’ – and went on his way’.

Leave a Reply