In the year I was born, 1952, just seven years after the end of the Second World War, the National Film Board of Canada in Montreal released a remarkable political film entitled Neighbours. Just over eight minutes long, it was the work of Norman McLaren, a Scottish director who’d settled in Canada. It was widely noticed at the time, and won many awards, but then fell out of public awareness.

Neither the film nor its maker was familiar to me, and I only found out about them while browsing in a fine but itself little-known book published by Unesco to publicise the documents inscribed in its ‘Memory of the World scheme.

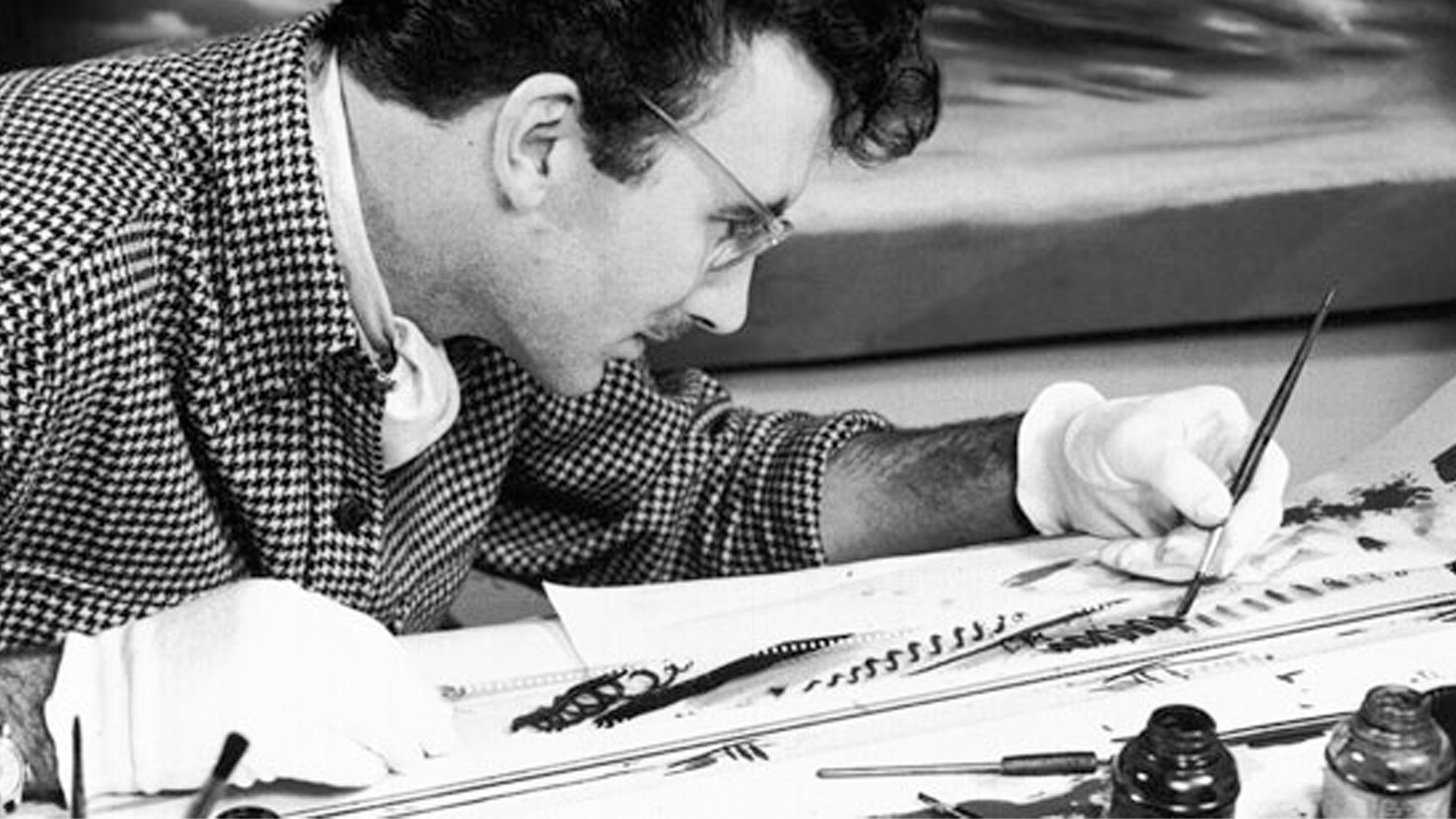

McLaren was one of the pioneering British film-makers, including Basil Wright, Paul Rotha and Humphrey Jennings, gathered around his fellow-Scot John Grierson in the GPO Film Unit. He worked for the Unit from 1936. His first, unpromising documentary, Book bargain (1937) documented the making of London telephone directories. More impressive is the quirky short Love on the wing (1938), ostensibly an advert for airmail letters, in reality a surrealist, near-erotic jeu d’esprit featuring McLaren’s homemade technique of drawing in pen and Indian ink directly on to 35mm film.

In 1939 McLaren moved to New York and developed his experimental methods. Here in 1940 he made Boogie-Doodle, an unsurpassably brilliant animation of the act of human sexual reproduction, to a sound track of Albert Ammons’s thunderous boogie-woogie piano (‘Boogie-woogie stomp’). Two other, even shorter abstract films were Dots and Loops, in which McLaren created the sound track by the same technique as he made the visual track, by ‘writing’ directly on the area of the filmstrip reserved for sound.

In 1939 McLaren moved to New York and developed his experimental methods. Here in 1940 he made Boogie-Doodle, an unsurpassably brilliant animation of the act of human sexual reproduction, to a sound track of Albert Ammons’s thunderous boogie-woogie piano (‘Boogie-woogie stomp’). Two other, even shorter abstract films were Dots and Loops, in which McLaren created the sound track by the same technique as he made the visual track, by ‘writing’ directly on the area of the filmstrip reserved for sound.

In 1941 Grierson, now in Canada, invited him to join the National Film Board, open an animation studio and train Canadian animators. He produced his own animations, including the witty, abstract Hen hop (1942), for which McLaren spent days in a chicken coop, capturing what he called the ‘spirit of henliness’.

In 1941 Grierson, now in Canada, invited him to join the National Film Board, open an animation studio and train Canadian animators. He produced his own animations, including the witty, abstract Hen hop (1942), for which McLaren spent days in a chicken coop, capturing what he called the ‘spirit of henliness’.

Ten years later, with Neighbours, McLaren replaced whimsy with the most serious of themes, war and peace, and animation with a new technique which one of his colleagues, Grant Munro, termed pixillation. The film uses two actors, Munro and Jean-Paul Ladouceur, but speeds up their movements and also uses a stop-frame technique.

We start with two pipe-smoking men sitting, amiably enough, in deckchairs on a lawn in front of their (cardboard) houses and reading newspapers: one has the headline ‘Peace certain if no war’, the other ‘War certain if no war’. All is still. They help each other to light their pipes. Then suddenly a yellow flower appears in the lawn. Each smells the flower, and gradually each develops a possessive desire for it. They start to squabble. One of them erects a fence of white stakes, enclosing the flower on his side of it. Soon the two men are fighting, first with fists, then using the palings as weapons. War paint appears on the face of each. Then, in a shocking scene censored from early versions of the film, each man destroys the house of the other and batters his wife and baby to death. Then they murder each other. The film ends with the white palings rearranging themselves around the graves of the two men. Two of them form a cross on each grave, and two yellow flowers climb on to the top. A multilingual caption ends the film. ‘Love your neighbour’, it says, simply – a quotation from the gospel of Mark, chapter 12.

We start with two pipe-smoking men sitting, amiably enough, in deckchairs on a lawn in front of their (cardboard) houses and reading newspapers: one has the headline ‘Peace certain if no war’, the other ‘War certain if no war’. All is still. They help each other to light their pipes. Then suddenly a yellow flower appears in the lawn. Each smells the flower, and gradually each develops a possessive desire for it. They start to squabble. One of them erects a fence of white stakes, enclosing the flower on his side of it. Soon the two men are fighting, first with fists, then using the palings as weapons. War paint appears on the face of each. Then, in a shocking scene censored from early versions of the film, each man destroys the house of the other and batters his wife and baby to death. Then they murder each other. The film ends with the white palings rearranging themselves around the graves of the two men. Two of them form a cross on each grave, and two yellow flowers climb on to the top. A multilingual caption ends the film. ‘Love your neighbour’, it says, simply – a quotation from the gospel of Mark, chapter 12.

The end of the film, and the murder of the wives and children, are all the more appalling because the film conforms so closely to the conventions of the early comedy movies of Chaplin, Keaton and Lloyd – slapstick and comic violence, jerky movement, jaunty music. And anyone familiar with McLaren’s earlier work, playful, innovative and quirky, would hardly expect the sheer viciousness of the film’s denouement.

The end of the film, and the murder of the wives and children, are all the more appalling because the film conforms so closely to the conventions of the early comedy movies of Chaplin, Keaton and Lloyd – slapstick and comic violence, jerky movement, jaunty music. And anyone familiar with McLaren’s earlier work, playful, innovative and quirky, would hardly expect the sheer viciousness of the film’s denouement.

Norman McLaren was a convinced communist from an early age. In his early twenties his father sent him to the Soviet Union to cure him of his affliction, but he came back even more convinced. He was also a committed pacifist. McLaren said, ‘I was inspired to make Neighbours by a stay of over a year in the People’s Republic of China. Although I saw only the beginning of Mao’s revolution, my faith in human nature was reinvigorated by it. Then I came back to Quebec and the Korean War began. I decided to make a really strong film about anti-militarism and against war.’

John Grierson was far from convinced by McLaren’s political film-making (‘I wouldn’t trust Norman around the corner as a political thinker. I wouldn’t trust Norman around the corner as a philosophic thinker’), but Neighbours won a Canadian Film Award and an Oscar, and it’s returned to public notice from time to time, at times of international turmoil and conflict, like the Vietnam War. Perhaps its message, simple and direct though it is, has something to say to us, in the era of engineered political hatred and division?

Leave a Reply