Until last week I’d never heard of the Mundaneum. But it’s such an exceptional institution that it deserves to be much better known.

Until last week I’d never heard of the Mundaneum. But it’s such an exceptional institution that it deserves to be much better known.

To visit the Mundaneum as it is today you need to go the Wallonian city of Mons and search out the Rue de Nimy. There, in an adapted department store, you’ll find a museum and archive, opened in 1998, that commemorates two remarkable Belgians, Henri La Fontaine and Paul Otlet. Their original archive has been called the first, analogue world attempt to bring all the world’s knowledge together in one place – what the internet and its search engines try to do today, without the need for a ‘place’. This is amazing enough, but there’s another side to the first Mundaneum: it represents an idealistic – maybe quixotic – attempt to forge a link between the availability of knowledge with the achievement of peace and social justice.

Henri La Fontaine was born in Brussels in 1854 and became known as an authority on international law. World peace became his prime concern. He was president of the World Peace Bureau from 1907 and played a role in the Hague Peace Conferences of 1899 and 1907. In 1913 he won the Nobel Peace Prize. After the disaster of the First World War he campaigned for the establishment of an international court (it finally came into being at the end of another world war, in 1945, two years after his death). La Fontaine was a socialist – he was a founder member of the Belgian Labour Party and sat in the Belgian Senate from 1895 – and, with his sister Léonie, a passionate advocate for women’s rights and women’s suffrage (he was present at the foundation of the Belgian League for the Rights of Women in 1892). It was another of his interests, the organization of knowledge, that brought him into a lasting collaboration with Paul Otlet, from 1891.

Henri La Fontaine was born in Brussels in 1854 and became known as an authority on international law. World peace became his prime concern. He was president of the World Peace Bureau from 1907 and played a role in the Hague Peace Conferences of 1899 and 1907. In 1913 he won the Nobel Peace Prize. After the disaster of the First World War he campaigned for the establishment of an international court (it finally came into being at the end of another world war, in 1945, two years after his death). La Fontaine was a socialist – he was a founder member of the Belgian Labour Party and sat in the Belgian Senate from 1895 – and, with his sister Léonie, a passionate advocate for women’s rights and women’s suffrage (he was present at the foundation of the Belgian League for the Rights of Women in 1892). It was another of his interests, the organization of knowledge, that brought him into a lasting collaboration with Paul Otlet, from 1891.

Otlet was a younger man, born in 1868 to a wealthy family (his father sold trams). Like La Fontaine he was born in Brussels, and also like him he trained as a lawyer, but tired of law and turned to bibliography. In his first publication, in 1892, he criticised the book as a unit of knowledge and advocated the atomisation of individual units of information held within it, and their separate ‘documentation’ (his coinage) so that they were easily retrievable. This was the genesis of Otlet’s favoured means of documentation, the catalogue card. As a method of ordering the subjects found in his information systems he later (from 1905) developed the work for which he’s well known by librarians, the Universal Decimal Classification, an extension of the Dewey Decimal Classification devised by the American Melvil Dewey in 1876. The UDC was more sophisticated than Dewey’s scheme in that it allowed semantic relationships between subjects to be represented in its numbers (an early hint of the ‘semantic web’).

Otlet was a younger man, born in 1868 to a wealthy family (his father sold trams). Like La Fontaine he was born in Brussels, and also like him he trained as a lawyer, but tired of law and turned to bibliography. In his first publication, in 1892, he criticised the book as a unit of knowledge and advocated the atomisation of individual units of information held within it, and their separate ‘documentation’ (his coinage) so that they were easily retrievable. This was the genesis of Otlet’s favoured means of documentation, the catalogue card. As a method of ordering the subjects found in his information systems he later (from 1905) developed the work for which he’s well known by librarians, the Universal Decimal Classification, an extension of the Dewey Decimal Classification devised by the American Melvil Dewey in 1876. The UDC was more sophisticated than Dewey’s scheme in that it allowed semantic relationships between subjects to be represented in its numbers (an early hint of the ‘semantic web’).

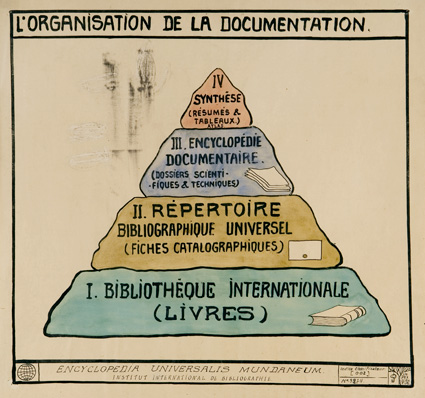

With these new tools Otlet and La Fontaine set about the (impossible) task of cataloguing the world’s knowledge. They called their catalogue the Repertoire Bibliographique Universel, and within a year of its beginning in 1895 it contained 400,000 cards, stored in huge banks of wooden catalogue cabinets. At its peak it contained 15m cards (a remnant is preserved in today’s Mundaneum). Enquirers from around the world could send in their requests for information and, for the price of 27 francs, receive a response, including copies of the original cards. Originally called the Palais Mondial, the system was housed in a wing of the Palais du Cinquantenaire, a government building in Brussels. It was later renamed the Mundaneum.

With these new tools Otlet and La Fontaine set about the (impossible) task of cataloguing the world’s knowledge. They called their catalogue the Repertoire Bibliographique Universel, and within a year of its beginning in 1895 it contained 400,000 cards, stored in huge banks of wooden catalogue cabinets. At its peak it contained 15m cards (a remnant is preserved in today’s Mundaneum). Enquirers from around the world could send in their requests for information and, for the price of 27 francs, receive a response, including copies of the original cards. Originally called the Palais Mondial, the system was housed in a wing of the Palais du Cinquantenaire, a government building in Brussels. It was later renamed the Mundaneum.

By 1910 Otlet and La Fontaine were ready to aim higher. They conceived the idea of a ‘world city’, a place that would bring together international organizations, including a world library and museum and university, and radiate knowledge, peace and cooperation throughout the world. Several architects, including Le Corbusier, drew up plans for the city. Needless to say, the City was never built. One wonders too about the reality or reach of some of the many world institutions the two men founded. They were inordinately fond of inventing new bodies, whose grandiose titles they always prefaced with the word ‘international’. These included the International Office of Sociological Bibliography, the International Office of Bibliography, the International Institute of Photography, the International Newspaper Museum, and the Central Office (and later, Union) of International Associations.

After the First World War the work of La Fontaine and Otlet seems to have lost public support. The age of aggressive nationalism was hardly fertile soil for their internationalist ideals and positivist faith in scientifically guided progress. One periodical complained that they were trying to ‘transform the whole of Brussels into a vast city of cards’. The Belgian government withdrew its funding and the Mundaneum closed to the public in 1934. The Nazis completed the job of closure in 1940 when they partially destroyed its collections to make room for an exhibition of Third Reich art. La Fontaine died in 1943 and Otlet in the following year.

After the First World War the work of La Fontaine and Otlet seems to have lost public support. The age of aggressive nationalism was hardly fertile soil for their internationalist ideals and positivist faith in scientifically guided progress. One periodical complained that they were trying to ‘transform the whole of Brussels into a vast city of cards’. The Belgian government withdrew its funding and the Mundaneum closed to the public in 1934. The Nazis completed the job of closure in 1940 when they partially destroyed its collections to make room for an exhibition of Third Reich art. La Fontaine died in 1943 and Otlet in the following year.

In the year of the original closure, 1934, Paul Otlet published a work that established himself as not just a deviser of documentary systems and bodies but as a thinker of real originality. The book was called Traité de documentation and in it he brought together his ideas about the future of the organization of knowledge.

Otlet had proved his credentials as an ingenious inventor before the War. In 1906 he adopted the microfiche as a means of miniaturising information, and in the same year anticipated the coming of the wireless telephone. An undated sheet from around 1920 seems to sketch a phone conference (séance de comité), a videoconference, and a means of remotely transmitting the contents of books and Otlet’s beloved catalogue cards through a television (a prophecy of the World Wide Web). He also came up with the idea of a Mondothèque, a workstation giving access to the world’s knowledge and connected to remote knowledge by radio and television. He had a phrase to describe this interconnectedness: réseau mondial – a worldwide network. And this is how it would work:

Toutes les choses de l’univers, et toutes celles de l’homme seraient enregistrées à distance à mesure qu’elles se produiraient. Ainsi serait établie l’image mouvante du monde, sa mémoire, son véritable double. Chacun à distance pourrait lire le passage lequel, agrandi et limité au sujet désiré, viendrait se projeter sur l’écran individuel. Ainsi, chacun dans son fauteuil pourrait contempler la création, en son entier ou en certaines de ses parties. (Monde: essai d’universalisme, 1935, p.391)

Everything in the universe and everything of man would be recorded remotely as it was produced. So the moving image of the world would be created – its memory, its faithful copy. Each person could read the text remotely, enlarged and limited to the desired topic, projected on an individual screen. So, from his armchair, each person would be able to look at the work, in whole or in part.

In the Traité Otlet goes even further. He seems to foresee the day when all knowledge will be available to a person as a biotechnological implant or transhuman organ:

In the Traité Otlet goes even further. He seems to foresee the day when all knowledge will be available to a person as a biotechnological implant or transhuman organ:

Le Livre Universel formé de tous les Livres, serait devenu très approximativement une annexe du cerveau, substratum lui-même de la mémoire, mécanisme et instrument extérieur à l’esprit, mais si près de lui et si apte à son usage que ce serait vraiment une sorte d’organe annexe, appendice exodermique. (Traité, 52B)

The universal book created from all books would become very approximately an annex to the brain, its own substratum of memory, an external mechanism and instrument of the mind, but so close to it, so well-adapted to its use, that it would truly be a kind of attached organ, an exodermic appendix.

You wonder how such a fertile brain as Otlet’s would have reacted, had he lived in a slightly later age, to the nexus of computer and telecommunications technologies and their possibilities. He would have been contemptuous perhaps of the bazaar-like nature of the Web, and the dumbness of our current internet search engines, with their habit of distorting search results through commercialisation (overt and covert) and personalisation. His solutions to organising knowledge always gave a leading role to human systematising, represented by cataloguing and classification. Even Wikipedia, the best approximation to what he intended, he would have found distressingly open and amateur.

Most histories of the internet are highly Anglo-American in the way they trace the genealogy of the internet and the Web. They concentrate on figures like Vannevar Bush, Ted Nelson and Vint Cerf. Few mention the conceptual boldness of Paul Otlet and his remarkable innovations.

But what’s just as interesting as the technological breakthroughs and ambitions of La Fontaine and Otlet is what drove them to take an interest in the organisation and communication of knowledge in the first place. Their motivation must have been the old Socratic equation, paradoxical and utopian though it seems to most people, between knowledge and virtue, between awareness of what is good and the doing of good. The conviction shared by the two men was surely that, if only men and women had the means to reach a true understanding of themselves and knowledge about the world, the destructive forces of war, nationalism and inequality could be overcome and a new age of international cooperation might dawn. If that conviction was badly damaged by two world wars and the other horrors of the twentieth century, it is hardly easier to promote in our own age, one of resurgent fascism and widespread contempt for the value of knowledge.

But what’s just as interesting as the technological breakthroughs and ambitions of La Fontaine and Otlet is what drove them to take an interest in the organisation and communication of knowledge in the first place. Their motivation must have been the old Socratic equation, paradoxical and utopian though it seems to most people, between knowledge and virtue, between awareness of what is good and the doing of good. The conviction shared by the two men was surely that, if only men and women had the means to reach a true understanding of themselves and knowledge about the world, the destructive forces of war, nationalism and inequality could be overcome and a new age of international cooperation might dawn. If that conviction was badly damaged by two world wars and the other horrors of the twentieth century, it is hardly easier to promote in our own age, one of resurgent fascism and widespread contempt for the value of knowledge.

If you’d like to know more about Paul Otlet and the Mundaneum read Alex Wright’s excellent book, Cataloguing the world: Paul Otlet and the birth of the information age, Oxford, 2014. W. Boyd Rayward, an Australian scholar who helped to resuscitate the Mundaneum, has also written about Otlet.

Leave a Reply