As I was wandering round the Manx Museum in Douglas last week – it’s a first-class museum with imaginative displays and zero dumbing-down – a name sprang out of one of the panels in the section on Manx prehistory that took me straight back to my student archaeology days. The name was that of Gerhard Bersu, who in the 1930s excavated Little Woodbury in Wiltshire, a farmhouse site that revealed for the first time how people in southern Britain lived in the late Iron Age. What I’d failed to appreciate back in the 1970s was that Bersu himself had a story that tells us a great deal about our parents’ time – and ours.

As I was wandering round the Manx Museum in Douglas last week – it’s a first-class museum with imaginative displays and zero dumbing-down – a name sprang out of one of the panels in the section on Manx prehistory that took me straight back to my student archaeology days. The name was that of Gerhard Bersu, who in the 1930s excavated Little Woodbury in Wiltshire, a farmhouse site that revealed for the first time how people in southern Britain lived in the late Iron Age. What I’d failed to appreciate back in the 1970s was that Bersu himself had a story that tells us a great deal about our parents’ time – and ours.

Gerhard Bersu was born in Jauer in Silesia (today in Poland, then part of Germany) in 1889. He developed an interest in archaeology as a schoolboy and later took part in excavations in several European countries, including Italy, Greece and Romania. By his early twenties he was already recognized as an outstanding archeologist, with an acute eye and a determination to document his findings accurately. During the First World War he was in charge of the organization responsible for protecting monuments on the Western Front. After the end of the war he joined the Cease Fire and Peace Delegation to help arrange the return of cultural property. In 1924 he joined the staff of the German Archaeological Institute in Frankfurt-am-Main and became its director in 1931. But Bersu was a Jew, and after the Nazis came to power he was stripped of his position and demoted in 1935, and forced to resign altogether in 1937.

With his wife Maria, an art historian, Bersu came to Britain in 1937, at the invitation of the Prehistoric Society (possibly Grahame Clark, one of its founders, was the moving force), specifically to use his advanced excavation methods and documentation expertise in order to excavate Little Woodbury (1938-39), the first dig the Society had sponsored. The meticulous excavation, and Bersu’s identification of postholes and storage pits, opened archaeologists’ eyes for the first time to the nature of Iron Age houses (some of them had previously believed such people lived in holes in the ground).

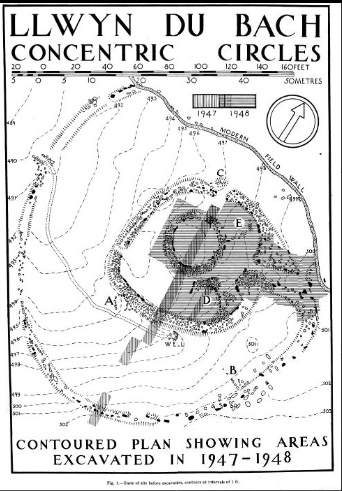

Gerhard and Maria were still German citizens and when war was declared they fell victim to the UK government’s policy of interning all enemy aliens, even those with no fascist sympathies. They were transported to the Isle of Man, eventually living together in a camp at Port St Mary. The supervision of the internees was clearly enlightened, because from 1941 Gerhard and Maria were allowed to make use of their archaeological skills in a series of digs organized by the then acting director of the Manx Museum, Eleanor Megaw, and staffed by camp inmates. Gerhard acted as director, under armed guard, and Maria did the documenting. The sites they worked on included two round mounds of Iron Age date at Ballacagan and Ballanorris, as well as a Viking ship burial at Chapel Hill, Balladoole. When the war finished the two of them continued to excavate on the Isle of Man (they had excavated around ten sites by the end), and in Ireland and in Wales, at Llwyndu Bach, near Penygroes, and at Braich-y-cornel, Cwm Ystradlyn. Llwydu Bach, which Bersu dug in 1947-48, contained a circular stone-based house site enclosed by two concentric circles and may have dated from the pre- or post-Roman period.

Gerhard and Maria were still German citizens and when war was declared they fell victim to the UK government’s policy of interning all enemy aliens, even those with no fascist sympathies. They were transported to the Isle of Man, eventually living together in a camp at Port St Mary. The supervision of the internees was clearly enlightened, because from 1941 Gerhard and Maria were allowed to make use of their archaeological skills in a series of digs organized by the then acting director of the Manx Museum, Eleanor Megaw, and staffed by camp inmates. Gerhard acted as director, under armed guard, and Maria did the documenting. The sites they worked on included two round mounds of Iron Age date at Ballacagan and Ballanorris, as well as a Viking ship burial at Chapel Hill, Balladoole. When the war finished the two of them continued to excavate on the Isle of Man (they had excavated around ten sites by the end), and in Ireland and in Wales, at Llwyndu Bach, near Penygroes, and at Braich-y-cornel, Cwm Ystradlyn. Llwydu Bach, which Bersu dug in 1947-48, contained a circular stone-based house site enclosed by two concentric circles and may have dated from the pre- or post-Roman period.

In 1947 Bersu moved to Dublin to work for the Royal Irish Academy but returned to Germany in 1950 and resumed his directorship of the German Archaeological Institute. He rebuilt the Institute and opened its new building in Frankfurt before retiring in 1956 (he died in 1964, while attending an archaeological conference).

Today Bersu is recognized as one of the greatest German archaeologists of the twentieth century. His influence on a generation of British prehistorians, including Grahame Clarke, Christopher Hawkes and Stuart Piggott, was profound. He’s still well-remembered in the Isle of Man, and his excavation reports on three sites he excavated during the war were finally published by the Manx Museum in 1977. Francis Pryor points out that Bersu found flints on the floor of one of the Iron Age houses, and plausibly suggested that they had come from soil placed on the roof of the house in place of thatch.

Pryor also wonders whether Gerhard and Maria Bersu would have been treated so positively by the authorities today. It’s very doubtful. Theresa May’s ‘hostile environment’ for immigrants and refugees would probably have refused them entry to Britain in the first place, and even if they had been allowed entry it’s more likely that they would be held indefinitely in a detention centre rather than being allowed the freedom to conduct archaeological excavations. Xenophobia, racism and fascism, promoted by sections of the media and abetted even by the BBC, are again at large in Britain, in a way unknown since the 1930s. It’s now hard to believe that those in power in Britain today would allow the citizens of a hostile country, in a time of war, the freedom to contribute their expertise to increasing scientific knowledge about the past. That offering asylum and encouragement to refugees is not only humane but brings benefits to the host country seems an increasingly eccentric idea.

Leave a Reply