In the huge and magnificent William Blake exhibition now on in Tate Britain there are many images that were new to me, even though I’d seen the earlier big Tate shows of his artistic work, in 1978 and 2000. One of them comes from a series Blake produced during the last three years of his life – he died in 1827 – that has, until recently, escaped critical attention.

The series of twenty-eight illustrations, possibly commissioned by an unknown person, feature scenes from John Bunyan’s The pilgrim’s progress, first published in 1678. It’s not hard to see how Bunyan’s story, the story of Christian’s ‘dangerous journey’ on foot from the City of Destruction to the Celestial City, might have appealed to Blake’s imagination and his taste for religious and political dissent. (In death the two are still linked: their bodies lie within a few feet of each other in the dissenters’ cemetery of Bunhill Fields in London.)

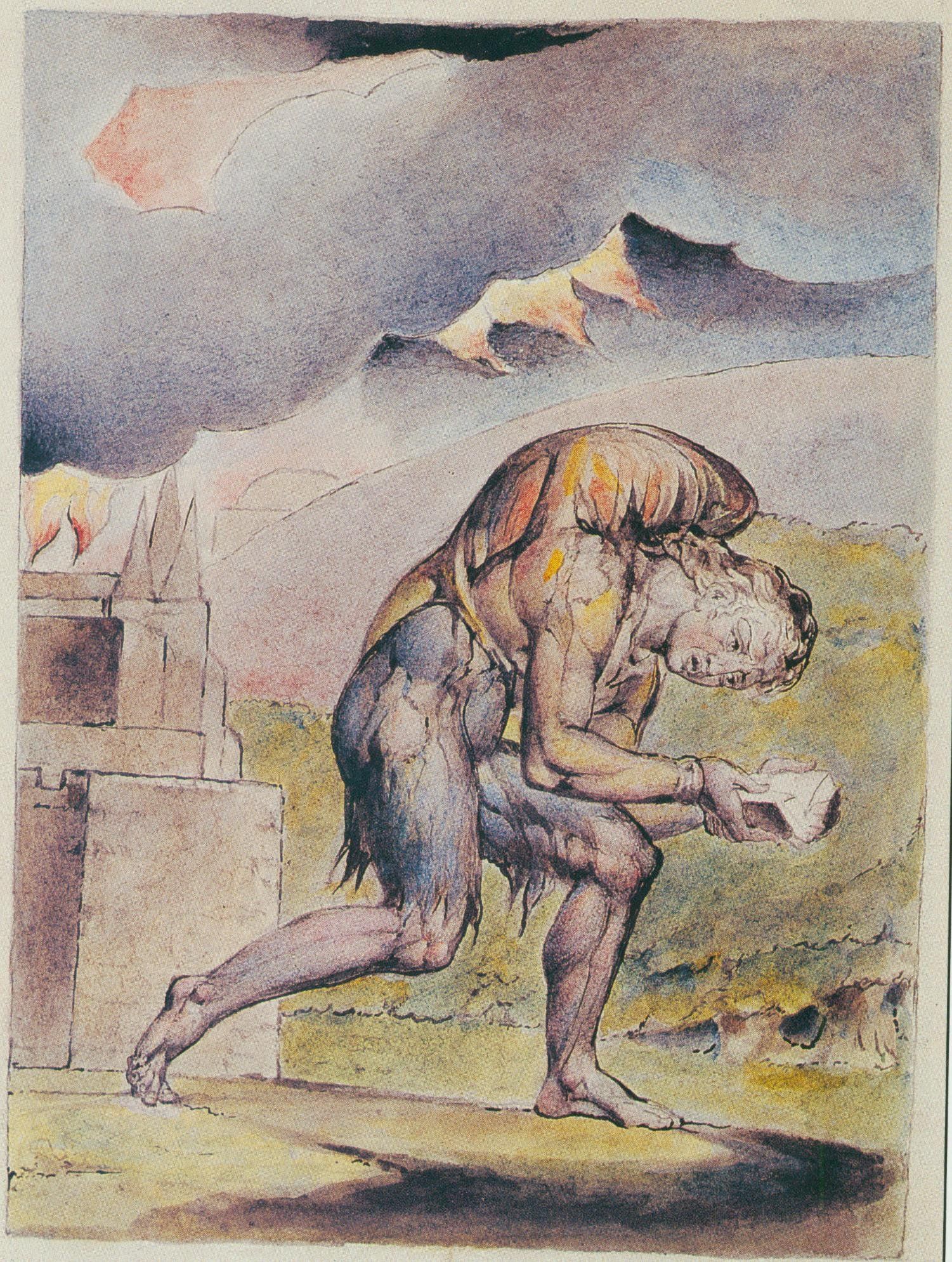

There’s no evidence that Blake intended his pictures to illustrate a new edition of Bunyan’s text. He may have seen them as a stand-alone sequence, an ‘alternative’ way of imagining Christian’s journey. It’s suggestive that their portrait format and size (around 16 to 19cm by 13cm) are both book-like. The first image is of Christian at the start of his journey.

Blake’s picture could be taken from the first words of The pilgrim’s progress, with their plain but carefully sculpted prose:

As I walked through the wilderness of this world, I lighted on a certain place where was a Den, and I laid me down in that place to sleep: and, as I slept, I dreamed a dream. I dreamed, and behold, I saw a man clothed with rags, standing in a certain place, with his face from his own house, a book in his hand, and a great burden upon his back.

Christian returns to his house for a heart-to-heart with his family. He tells his troubles can only be relieved by escaping from their city, which is about to be destroyed by ‘fire from heaven’. Not unreasonably, they suspect mental illness (‘they thought that some frenzy distemper had got into his head’) and turn against him: ‘sometimes they would deride, sometimes they would chide, and sometimes they would quite neglect him’. (Could this scene possibly have been the inspiration for Franz Kafka’s story Metamorphosis?) Christian is still in torment, and spends time outside, praying and reading:

Now, I saw, upon a time, when he was walking in the fields, that he was, as he was wont, reading in his book, and greatly distressed in his mind; and, as he read, he burst out, as he had done before, crying, ‘What shall I do to be saved?’

So this is the second possible point in the text that Blake set to illustrate in his first image. (Christian’s anguished question is answered by Evangelist, who appears before him, to show him the wicket-gate and shining light that will set him on the long road towards the Celestial City.)

Blake’s Christian is typical of his image of suffering humanity: a well-muscled figure bent low under his heavy rucksack – it presumably contains the sins of his past – and clad in short leggings, reduced to a few thin rags. His face is absorbed in his book. Bunyan doesn’t specify what book it is, but he has no need to: it must be the Bible. (Today’s walker would be more likely to be tortured by the effort of trying to make sense of an inadequate guidebook.) Behind Christian is the about-to-be destroyed city of sin, overlooked by bare mountains and already threatened by a red hint of the ‘fire from heaven’. As an image of physical and mental pain it could hardly be bettered in William Blake’s work.

But is it William Blake’s work? Since the mid-nineteenth century there have been suspicions that his wife Catherine was responsible for much of the Pilgrim’s progress sequence, especially for colouring the pictures (the colouring of some remains unfinished). The Frick Collection in New York once owned it, but, according to the Tate’s catalogue, deaccessioned it in 1996 because its curators felt that Catherine’s role in producing it reduced its worth and interest. Today that behaviour appears scandalous. There’s no doubt about Catherine’s key part in helping to produce her husband’s printed works, and it may be that her (unacknowledged) role extended well beyond technical assistance. One of Blake’s patrons, William Hayley, wrote

… she [Catherine] draws, she engraves, & sings delightfully & is so truly the Half of her good Man, that they seem animated by one Soul, & that a Soul of indefatigable industry and benevolence.

If Catherine was in large part responsible for the Pilgrim’s progress pictures, we can only give thanks to her. They contain some of the most vibrant and alive images in the whole of the Blakes’ artistic work, like ‘Christian fears the fire from the mountain’, ‘Christian at the arbour’ and ‘Christian fights Apollyon’. On his death bed William said that Catherine had ‘ever been an angel’ to him. She was clearly a highly interventionist angel. She said of him, ‘I have very little of Mr Blake’s company; he was always in Paradise’. While he was otherwise engaged, it seems, Catherine was busy with her pen and brushes.

Leave a Reply