Alluring women in chiffon and sandals, bright marble benches, azure seas, flower petals falling like rain. This was the recipe Lawrence Alma-Tadema hit on for his paintings of scenes from ancient Rome. Thousands were drawn to buy them, or at least reproductions of them, in late Victorian and Edwardian England.

It was all a long way from where the artist began. One of the virtues of the big exhibition of his works in Leighton House Museum is that you can trace Alma-Tadema’s progress from his origins in Dronryp, a village in Friesland in the north of the Netherlands, to fame and the high life in London in the early years of the 20th century. The show comes from the Museum of Friesland in Leeuwarden and many of the earliest paintings belong to Dutch collections. In his early years in the Netherlands Lourens Alma Tadema – his pre-anglicised name – produced history paintings, still the supreme genre at the time. They’re dark and portentous in comparison with his later works, and they specialise in uplifting scenes from Merovingian history and myth. Tadema was also an accomplished portraitist. His 1852 self-portrait shows a bright, self-confident young man, sporting a very contemporary, 2010s quiff.

In 1863 he married Pauline Gressin and during their Italian honeymoon they stayed at Naples and visited Pompeii. For over a century the streets, houses, shops and brothels of the ancient town had gradually been brought to light. In 1860 Giuseppe Fiorelli had taken over as director of excavations at Pompeii and brought a new, scientific rigour to the work. He began to discover traces of the bodies of those overcome by the eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79, and to create plaster casts of them. A visit to Pompeii was already famous as a short cut to experiencing the life of a Roman town, and those who could not visit could marvel at the astonishingly complete remains in the many publications that followed. The sudden death of the town and its inhabitants appealed to the morbid tastes of Victorian Britain – Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s novel The last days of Pompeii had played upon these feelings in 1834 – but Pompeii held a parallel fascination, for its erotica. Since the eighteenth century evidence – wall paintings, graffiti, pottery, votive phalluses and other objects – had uncovered of the keen sexual interests of the inhabitants, a source of endless curiosity to the buttoned-up English.

In 1863 he married Pauline Gressin and during their Italian honeymoon they stayed at Naples and visited Pompeii. For over a century the streets, houses, shops and brothels of the ancient town had gradually been brought to light. In 1860 Giuseppe Fiorelli had taken over as director of excavations at Pompeii and brought a new, scientific rigour to the work. He began to discover traces of the bodies of those overcome by the eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79, and to create plaster casts of them. A visit to Pompeii was already famous as a short cut to experiencing the life of a Roman town, and those who could not visit could marvel at the astonishingly complete remains in the many publications that followed. The sudden death of the town and its inhabitants appealed to the morbid tastes of Victorian Britain – Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s novel The last days of Pompeii had played upon these feelings in 1834 – but Pompeii held a parallel fascination, for its erotica. Since the eighteenth century evidence – wall paintings, graffiti, pottery, votive phalluses and other objects – had uncovered of the keen sexual interests of the inhabitants, a source of endless curiosity to the buttoned-up English.

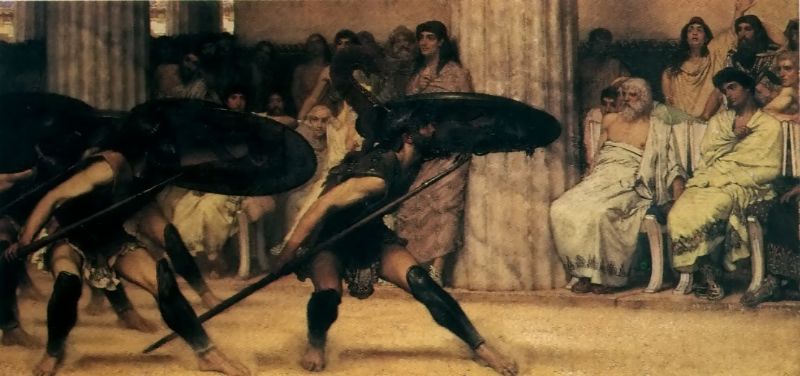

Tadema was transfixed by Pompeii, and started to document for future reference the details of Roman architecture, clothing, furniture and other objects excavated there. The experience changed his painting for good. He gave up painting obscure moments from medieval European history and turned instead to imagining scenes from Roman history and life: Catullus’s Lesbia weeping over a sparrow, Entrance to a Roman theatre, and a bold, martial composition, A Pyrrhic dance. Flowers, so important in the later art, began to make an appearance. Historical authenticity, in the depiction of interior decoration, furniture and costume, was something Tadema prized – and probably expected his buyers to appreciate. Keener students, for example, would have spotted, on the wall behind the figures in A Roman lover of art, the famous mosaic of Alexander at the Battle of Issus. But he didn’t felt imprisoned by the need for veracity, and his Roman women are never very far in appearance from the graceful English women who modelled for him. Richard Jenkyns calls them ‘Victorians transported into a sunny realm of perpetual holiday’.

In 1867 Pauline died. Tadema came to England and fell in love with a seventeen year old English girl, Laura Epps. In 1871 they were married and lived for the rest of their lives in London. Laura too became a painter (as did Tadema’s two daughters), and the pair turned a large building near Regent’s Park into a house and studio. By now Tadema’s palette had lightened, perhaps under Pre-Raphaelite influence, and Roman scenes were his staple. Sometimes these were historical, more often they were generalized pictures, often of dreamy young women (and men) on marble benches. Coign of vantage (1895) is a fine late example. Three girls stand on a marble terrace high above the sea and in front of a garlanded lion statue. One leans back languidly while the other two peer over the wall at men rowing in a boating race far below. Tadema lavishes care on the detail of their fine dresses and expensive hair, decked with flowers. There’s nothing indecorous about the picture, just an aura of latent sexuality, in the depiction of the figures and the vaguest sense of erotic anticipation built into the scenario.

There was a lively English appetite for paintings like Coign of vantage. Interest in the classical world was probably at its strongest. Greek, Latin and ancient history were an inescapable part of the education of young gentlemen, in the public schools and beyond. Classical art and literature abounded in social and sexual themes that were strictly excluded from the ways the Victorian middle classes were expected to lead their public lives. Alma-Tadema’s versions of antiquity gave his customers suggestive access to this attractive world, without offending directly against prevailing mores.

Apart from satisfying his market, did Alma-Tadema have his own artistic vision or did he share in artistic movements of his time? His later career coincided with the decadent movement, but it’s difficult to detect much connection between his paintings and the chancier world of Swinburne and Oscar Wilde. Despite the transgressive tendencies of the ‘decadents’ and the many opportunities offered by the ancient world, Tadema seems little interested in unconventional sexuality. Indeed, the erotic in any form is heavily sublimated in his paintings. It’s true that he was sometimes drawn to episodes of excess from the later Roman empire, as in his late tour de force The roses of Heliogabalus, but even this golden opportunity Tadema seems to let slip.

The hedonistic and probably transgender emperor Elagabalus (Heliogabulus) is said by the Augustan History (a source as reliable as the Sun or Daily Mail) to have invited guests to a banquet and buried them in a rain of flower petals, ‘so that many were smothered to death, being unable to crawl out’. In Tadema’s picture the emperor and his entourage recline in an elevated triclinium, while in the foreground a great shower of rose petals falls on the guests. Most of them are obscured, but one woman can be seen, staring at us with an improbably impassive look. It’s as if Tadema has deliberately drained the scene of sensuality and excess. All that’s left is the painter’s orgiastic delight in flowers – he’s said to have had thousands of rose petals imported from the French Riviera to his studio during the winter of 1887-88 when he was working on the painting.

Perhaps the sad truth is that Alma-Tadema’s Dutch protestant roots simply wouldn’t allow him to give full rein to his sensual instincts in his art.

Leave a Reply