Bruges may be his birthplace and where you’ll find his museum, but Swansea has a claim to be the second home of Frank Brangwyn, ever since his huge ‘British Empire’ panels were diverted from the House of Lords in London to Swansea’s Guildhall in 1933. Today it’s possible to see Brangwyn’s visions of the fruits of every continent not as an expression of triumphant British imperialism, but as a celebration of the richness and variety of the biosphere, now under threat from human greed and thoughtlessness.

Brangwyn was a prolific painter, but he worked in many different media, including glass, furniture and decorative arts. Along with many other contemporary artists like Whistler, Sickert and Augustus John, he excelled at etching. Recently I bought a copy of the catalogue of the centenary Brangwyn exhibition organised in 1967 by the National Museum of Wales and the Welsh Arts Council (it features a striking cover by the talented designer Brian Shields). Among the zinc etchings illustrated, one caught my eye. Its title is ‘Breaking up the Hannibal’.

HMS Hannibal was one of a successive series of British warships of that name. It was launched at Deptford on 31 January 1854, as a ‘second rate’ ship, with a wooden hull, new screw propulsion and 91 guns. It was used for transporting French troops in the Crimean War, and Garibaldi’s troops to Italy in 1860 (when many on board died in a smallpox outbreak). It was ‘hulked’ – stripped of equipment and left floating – in 1874, and spent its final years as a depot ship for seamen. In 1904 it was taken to Castle’s shipbreaking yard at Charlton on the banks of the Thames, and was broken up.

Brangwyn wasn’t the only artist attracted by the melancholy sight of the dying Hannibal. William Lionel Wyllie, a specialist marine artist, produced a watercolour painting, now in the National Maritime Museum, of the Hannibal being broken up. There’s a second redundant warship, the Duke of Wellington, in the picture. It was built in Pembroke Dock in 1852 as a dual sail-steam ship. Like the Hannibal, she was equipped with the new screw propulsion and at the time of its launch was reckoned to be one of the most powerful warships in the world. Like the Hannibal she saw service in the Crimean War, but was also retired early, as ‘ironclads’ superseded wood-hulled ships. At Charlton, vast quantities of timber were removed from both vessels and lay on the foreshore until quite recently.

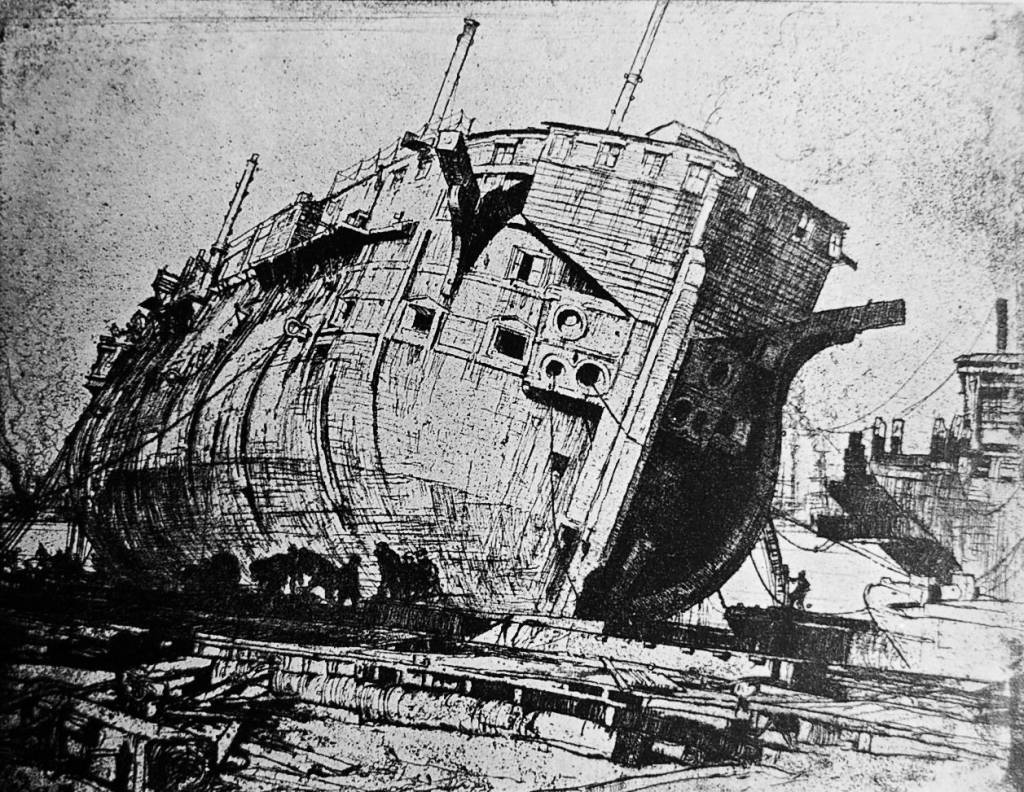

Wyllie’s painting views the two ships from far across the water – sea and sky dominate the composition – and the effect is far from dramatic. Brangwyn, on the other hand, gets close up to the Hannibal, whose huge bulk dominates his composition. He wrote to a friend at the time, ‘went down the river and have made an etching of an old line of Battle Ship being broken up, a splendid subject but awfully cold working out of doors.’ The Welsh writer on art Walter Shaw Sparrow, who published a book of Brangwyn’s prints and drawings in 1919, found the choice of viewpoint off-putting:

The hulk is brought too close to my eyes, occupying so much of a large plate (24J” by 19-2″) that I cannot see her poetry because I see overmuch of her bulk. In 1838, when Turner painted The fighting Temeraire towed to her last berth to be broken up, he was governed by that enchanted modesty which places the elements of poetry in their right places and in their proper scale. The Temeraire and her paddle-wheel tug are surrounded by a great seascape and a visiting sunset, yet they are all the world to anyone who loves our Navy and the sea as Turner loved them. As a big study full of apt concentration, Brangwyn’s “Hannibal” is very good; but yet … it seems to me that he ought to have achieved more because his emotion was all of a piece with Turner’s.

This way of looking at the work seems perverse. It’s precisely the close-up of the Hannibal that gives Brangwyn’s print its melancholy grandeur. Here the huge hulk lies, beached in the sun and listing among the debris of the breaking yard. Miniscule dock workers, silhouetted against the keel, toil beneath, their heads and bodies bent over. The breaking has only just begun, but the ship already looks naked and stripped. Dark holes gape in its flank, and the stumps of three masts are almost all that remain above the deck line.

Brangywn worked in the realist style of contemporary European artists – he was always attracted, for example, to scenes of manual workers at work and in movement – but he also saw himself as the heir of a longer, Romantic tradition. He would have been well aware of Turner’s ‘Temeraire’, and the dying ship was a theme in his own work. He again chose etching as the medium to depict the breaking up of three other ships, the Caledonia (1906), the Duncan (1912) and the Britannia (1917). All of them share the dramatic lighting and perspective of the Hannibal picture.

For the Romantic sensibility, the breaking up of once great ships was a modern variation on the architectural ruin, so strong a feature of paintings and drawings since the eighteenth century. It spoke of the fragility of human achievement and the ephemerality of empire. A perfect combination of grandeur and melancholy, the ruin was an inescapable visual metaphor for the trope ‘all things must pass.’ It’s still a very powerful theme today: take, for example, the astonishing photographs taken a couple of decades ago by Yves Marchand and Romain Meffre of the great ruined buildings of Detroit.

Brangwyn’s hulks were all warships. Did he have an intuition, I wonder, that British naval power and military dominance were already beginning to wane, in the years before the First World War, and that ‘breaking up’ was to be a wider metaphor for Britain for a century and more to come?

Leave a Reply