In 1892 Edgar Degas was around 58 years old. Not old, certainly by our standards, and he had twenty years and more left to live. But the landscapes he painted in the 1890s tend to get called ‘late paintings’, with good reason. Degas was a Parisian, an urban painter, and the works of his youth and maturity are mainly located in cities and suburbs: the opera and ballet, workshops, race meetings. They also tend to concentrate on the human figure, including portraits.

But from around 1890 Degas found a new interest: painting places in the French countryside. The only solo exhibition held in his lifetime, in November 1892, consisted entirely of landscapes. No one could have anticipated it. Degas had always been contemptuous of rural art, and especially plein-air painting. Of his friend Henri Rouart he said, ‘There’s Rouart, who painted a watercolour on the edge of a cliff the other day! Painting is not a sport!’ And just as mordant: ‘With a bowl of soup and three old brushes, you can make the finest landscape ever painted’.

The new landscapes used three techniques, coloured monotype printing, oil paint and pastel. The most remarkable are the fifty or so monotypes. In size no larger on average than 30 x 40 cm, they began during a visit in late 1890 to a friend who lived in a village near Dijon, in a house equipped with a printmaking studio. The medium appealed to Degas for its fluidity and uncertainty of outcome. He used earthy and green inks in works like Burgundy landscape, Twilight in the Pyrenees and Squall in the mountains to create imaginative reconstructions of small slices of countryside, and to suggest the atmospheric conditions that surround them. We’re told that he smeared the inks on the metal plates in any way he could: with brushes, rags, fingers and thumbs. Monotype was not exactly a new departure for him, but by the 1890s, when his eyesight was beginning to worsen, he was ready for experiment and radical change, in method and outcome.

Accident and chance produced striking images. In Forest in the mountains a large, irregular gash of dark ink has pushed its way into the picture from the side; left unexplained, it needs the viewer to supply an interpretation. In Squall in the mountains a wall of splattered paint mimics rain rushing in from the left to lash the hillside. The images may have been originally suggested by seeing real places, but Degas seems to have let them marinade in his mind, Proust-like, before turning to his inks and metal plates.

Another departure from tradition was technical. Monotypes are usually unrepeatable beyond the first pull, but Degas sometimes took a second impression, later working up with paint the paler and less distinct image that resulted, as in a view of the village of Estérel.

The monotypes are new, even revolutionary works. Despite his associations with them, Degas was never an Impressionist, and these prints move him even further from the vision of Monet and Renoir, rooted in the immediate, light-mediated response to real places. Yet they’re not symbolist either: the scenes don’t stand for ideas or mental states, and they never allow us to stray far from the metal plate that gave birth to them.

The oil and pastel landscapes Degas painted slightly later (from 1896) are almost equally rewarding to explore. Many of them were painted in Saint-Valéry-sur-Somme, a village he’d known since childhood. The empty streetscapes of the village, like Village street, Saint-Valéry-sur-Somme, combine the moodiness and colour shifts of the monotypes with an interest in geometric shapes that suggests the paintings of Paul Cezanne, with which Degas was familiar. Richard Kendall, the Degas expert who died in 2021 and who did much to draw attention to the landscapes, showed how Degas used photography, in which he was interested in his later years, to suggest composition possibilities – but also how he ignored topographical exactitude when he came to plan his canvases.

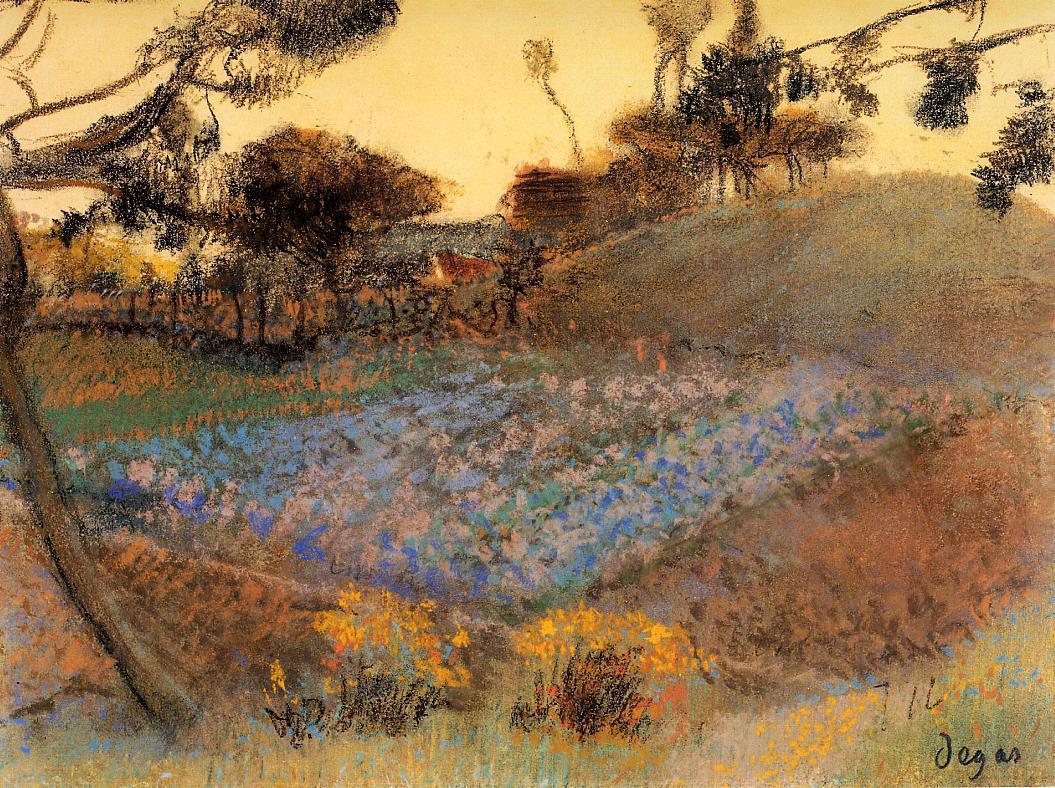

Some of the pastels are close in feel to the monotypes. The field of flax is another tiny window on to a country scene – this time, a diamond-shaped patch of blue flax flowers on the slope of a small hill, with clumps of yellow flowers in the foreground. It’s framed by wayward tree branches, and behind is a yellowy sky of dusk. The picture has the air of a dream or epiphany, as if Degas was recalling a scene from his early childhood. The urban, human, always active world of the early paintings – ballet dancers rehearsing, washerwomen ironing, orchestral musicians playing – has dissolved away, leaving a brief moment of solitary peace.

Degas never returned to landscape. He became more reclusive and cautious in old age, and produced few more turns in his artistic development. But his 1890s landscapes remain as works that continue to astonish. They fully deserve to be added to the examples of that Edward Said called the ‘late style’ of outstandingly creative people.

See Ann Dumas and others, Edgar Degas: the last landscapes, London: Merrell, 2006.

Leave a Reply