Lea Ypi’s Free: coming of age at the end of history, published in 2021, is a very unusual book. It’s at once a rite-of-passage memoir – Lea is around eight or nine years old at the start and is about to leave school for university at the end – and a child’s view of one of the most extreme changes of political gear experienced by any country in recent decades. And it’s a disguised work of political theory.

As a young child Lea was brought up in Durrës, a port city on the Adriatic to the west of Tirana, the capital of Albania, in the last days of communist rule. ‘I never asked myself’, runs the first sentence in her book, ‘about the meaning of freedom until the day I hugged Stalin’. The Berlin Wall has gone, and protests against the regime at home have begun, but for Lea’s schoolteacher, Nora, the communist rulers of the past, Josef Stalin and Albania’s own Enver Hoxha, are still gods to be idolised. Entirely convinced, Lea runs one day from the port to a garden near the Palace of Culture to give a hug to the huge bronze statue of Stalin (‘my arms struggling to circle the back of his knees’). She wants to find out whether he really did, as Nora claimed, ‘smile with his eyes’. But when she looks up, she finds to her horror that he has been decapitated. She can also hear the chant of the protestors, ‘Freedom, democracy, freedom, democracy’. What could it mean?

Lea’s trusting, unquestioning acceptance of the justice and benevolence of the Albanian state was strengthened not only by her schooling but also by her family. Her father and mother and her beloved grandmother, Nini, are, on the face of it, loyal adherents to the post-Hoxha government. Her father tells her the protestors are ‘uligans’. But they also keep silent about many things, and especially about their own history and forebears. We soon begin to understand, though Lea does not, that their evasions and silences disguise a very different reality. This part of the book recalls that other child’s eye view of adult horrors, Henry James’s What Maisie knew. Free, too, often feels like a novel in its use of invented dialogue, but also because, beyond the child’s voice, it’s multi-vocal, giving expression to different points of view.

Somehow, prospects for Lea’s family have been hampered by their ‘biography’, a birthmark as powerful and deterministic as one’s DNA: ‘once the word was said, you just had to accept it’. For members of Lea’s family, ‘biography’ refers not only to their bourgeois and intellectual origins, but to a murkier history: a prime minister in fascist times, known as the ‘Albanian quisling’, has the same, unusual family name. Lea finds out later that he is directly related to them. Both her grandfathers and several family friends have spent long periods in what her parents call ‘universities.’ What we suspect immediately is later confirmed: the ‘universities’ were really prison or re-education camps, punishment for ideological crimes. A man called Haki, one of the most severe university teachers, who ‘had a reputation for being highly committed to education’, was in reality a torturer. ‘Graduating’ meant completing a sentence, ‘dropping out’ meant committing suicide, and ‘being expelled’ meant a death sentence.

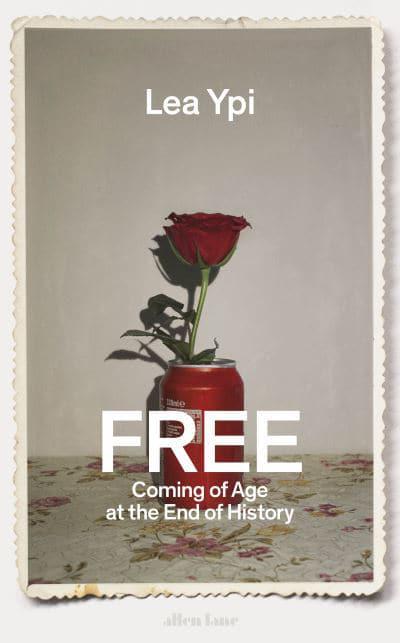

Albania was a country notoriously isolated from the rest of the world. Its citizens were not allowed to travel abroad, and the corrupting influences of the West were not allowed in. Fragments that do leak through, like Coca Cola cans, illicit television stations and occasional western tourists, loom large in Lea’s memory of her childhood.

Chapter 10, ‘The end of history’, is the hinge of the book. On 12 December 1990 Albania could no longer stand against the tide of change, and was officially declared a multi-party country. For Lea the end of the state brought a personal crisis: ‘in December 1990, the same human beings who had been marching to celebrate socialism and the advance towards communism took to the streets to demand its end’. Even more puzzling was the reaction of her parents, who ‘declared that they had never supported the Party I had always seen them elect, that they had never believed in its authority’. They begin to reveal some of the truths behind the secrets and lies about the family past. She realises that they have lied, again and again, in part to protect her, but also themselves. In Albania all the old slogans rapidly vanish, and only one remains: freedom. But when freedom arrives, it arrives ‘like a dish served frozen’.

Events now accelerate quickly. Elections are held. Lea travels to Greece with her grandmother in a vain search for ancestral ‘lost properties’. People try to flee to Italy to escape political chaos and poverty; some succeed, like Lea’s best friend Elona, others drown. Like many others, Lea’s father loses his job. His mother joins the political party in opposition. Western agencies, epitomised by ‘The Crocodile’, a sinister but ridiculous Dutch ’expert on societies in transition’ who works for the World Bank, force the shock therapy of ‘structural reforms’ on to the country’s economy. Lea’s father is now manager of the port, and is expected to sack many redundant workers. A decent and humane man, he cannot bear to take the decision. Millions lose their savings in fraudulent pyramid schemes. Finally, the country descends towards chaotic civil war. Lea describes the war in vivid diary form, but she herself, unable to cope with her confusion and the chaos around her, becomes more and more withdrawn. Her mother flees to Italy, her father later dies. But, when the school reopens, she sits her final exams, passes (as does everyone else), and announces to her family that she wants to study philosophy in Italy.

By now we understand that the book is shaped like a hinged mirror. The freedoms and terrible unfreedoms of the Hoxha era are replaced, or reflected, in the harsh neo-liberal years after 1990, by new freedoms for a few and disastrous unfreedoms for many.

The various meanings of political and personal freedom are a constant theme throughout the book, and it comes as little surprise to learn that Lea Ypi is now a professional philosopher (she teaches in the London School of Economics). In an epilogue she says that she’d started writing the book as a conventional book of philosophy, before finding that ‘ideas turned into people’ – people capable of rising above the social relations that formed them, but also people who were overwhelmed by realities much larger than them. Lea’s parents saw the socialist system as a denial of freedom; for her it was the ‘liberal’ system succeeding it that brought disappointment, destruction of solidarity, and injustice. The book’s epigraph is taken from Rosa Luxemburg, ‘human beings do not make history of their own free will. But they make history nevertheless’, and its dedication is to Nini, her grandmother, who embodies and upholds the role of human agency, will and dignity within each of the political systems she’s experienced.

Leave a Reply