Many people have praised Laura Cumming’s book On Chapel Sands: my mother and other missing persons (Chatto & Windus, 2019). It begins, like a novel, with a sudden disappearance: of her three-year-old mother, in summer 1929, from a sunny beach on the Lincolnshire coast. Like a detective story it pieces together what happened, and tries to break through the veil of long communal silence that fell over the event. Cumming is good at evoking the details of a remote, pre-war rural village, though it’s not a purely historical study, because her mother is still alive, and the sheets of silence are still partly in place.

On Chapel Sands is mainly about memory and remembering. What sets it apart is its examination of how ‘constructed memory’, even with the help of written, oral and visual evidence, might be unreliable, or at least tell nothing like the full story. Towards the end of the book Cumming begins to have doubts about the picture of her grandfather George that she’s built up gradually over the course of her long investigations. He seemed, from the evidence she could find, to be the villain of the piece – adulterer, virtual gaoler of his lonely illegitimate child, an unfeeling absentee husband. But she has to admit that she can imagine a different back-story for him, one that concedes to him at least some of the humanity that she attributes to his ‘victims’, including her own mother.

Cumming is best known as the excellent art reviewer of The Observer, and one of the striking features of her book is her penetrating use of the visual clues that remain of the puzzle, especially family photographs. One in particular, a Vermeer-like study taken by George of his young wife Veda, standing, bathed in soft lateral light, in the kitchen of their house, early in their marriage, is the spark that ignites her reappraisal of his character. Another portrait photo, probably taken, decades later, by Cumming’s mother, is the only one that shows Veda and George together. Veda looks directly at the camera (‘smiling sweetly’ at her adopted daughter, according to Cumming, although it’s hard to detect the smile in the reproduction in the book), but George, fist on hip, is deliberately looking away – evidence, Cumming feels, of his lack of intimacy and concern for either woman.

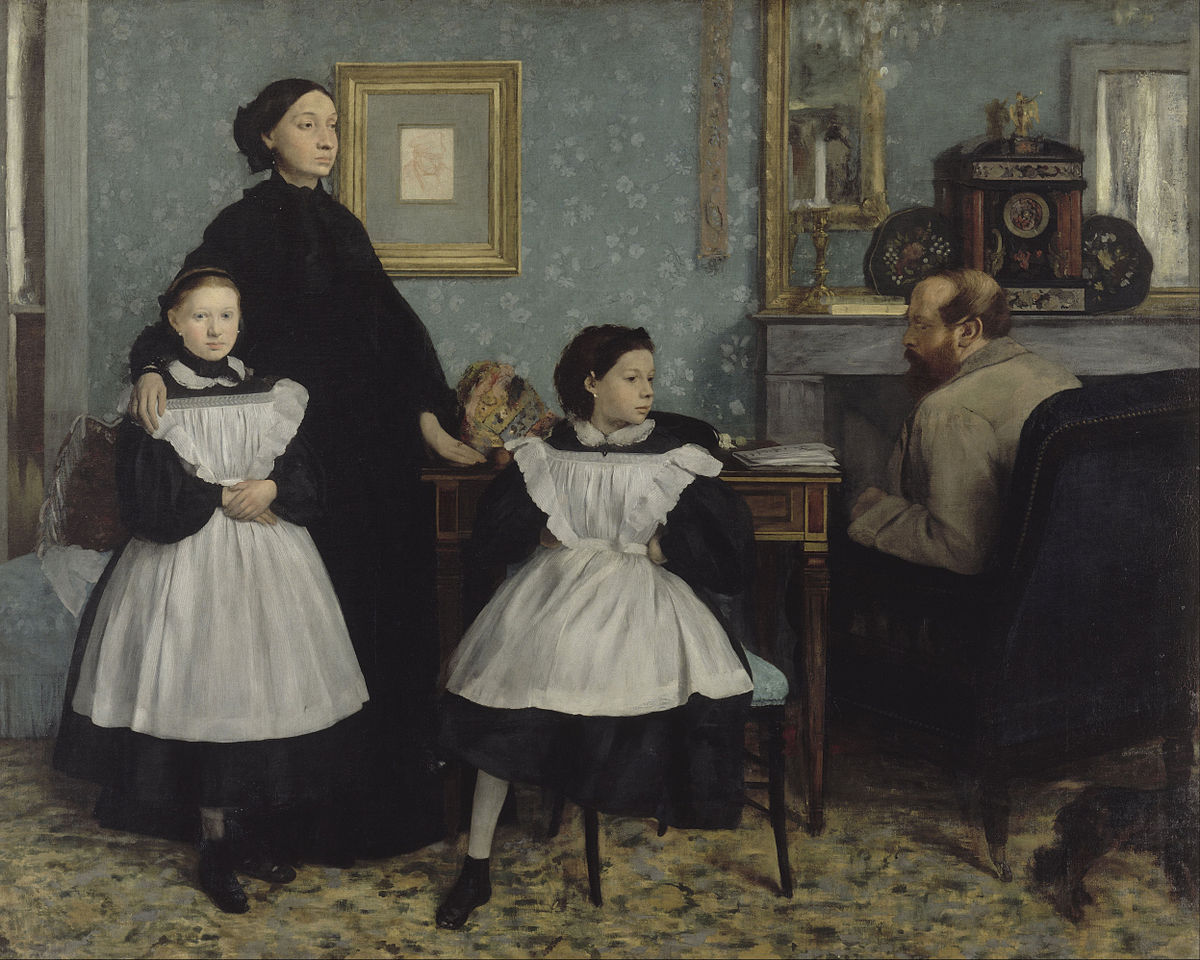

She offers the reader a parallel to this scene, from the world of painting so familiar to her, Edgar Degas’ early portrait of the Bellilli family, now in the Musée d’Orsay, Paris. This too is included in the book, in a tiny, almost unreadable black and white reproduction. (Cumming has many of these insets: she’s clearly following the example of W.G. Sebald in his own east-coast excavation of memory, The rings of Saturn.) She points out what a revolutionary painting this was.

From the Renaissance onward the family portrait usually followed a conventional formula. It demonstrated to the world the success of a constructed social unit: the husband, dominant and protective; the wife, dutiful, loving and fertile; the children, mischievous and playful, maybe, but, unless early death intervenes, guarantors of status and wealth preserved in time to come. Degas, a revolutionary in so many aspects of his art, upends this tradition, and subverts it, in his picture of Gennaro Bellilli, his wife and their two daughters.

This was not a portrait commissioned by strangers. Bellilli was an uncle of Degas, and his wife Laura was his aunt. Gennaro came from an aristocratic Italian family – he was a Count – but he was a liberal, opposed to the Bourbon rulers of Naples, and after the failure of the 1848 revolution was forced into exile from his home to Florence. In 1858 Laura invited Degas, then in Italy, to visit her in Florence. He stayed with the family, taking the opportunity to study the collections of the Uffizi Gallery, and to draw the life of the streets. He also made studies, in pencil, pastel and oil, of his young cousins, perhaps as preparation for a double portrait. In March the following year Degas left Florence and returned home to Paris. He seems to have worked on a family portrait for some years, presumably from the various studies he’d produced in Florence. In 1960 he returned to Italy, and made some studies of Gennaro. At some time later (when is unclear) he completed the oil painting of the whole family. It was not given to the Bellillis, was never sold during Degas’ lifetime, and remained in his studio, except for one possible showing at the Paris Salon in 1867 (by which time Gennaro was dead). When it reappeared in public, in 1918, it was almost immediately recognised as an outstanding work.

Even today ‘The Bellilli family’ strikes you as a very strange painting. It’s as far as you could imagine from the standard family portrait. Someone who wasn’t familiar with Degas might think, especially with the knowledge that it was built up from many individual studies of individual figures and parts of figures, that this was the awkward, gauche work of a beginner. At first sight the family members look unconnected, as if several different pictures had been crudely tacked together. But Degas was already in his mid-twenties, and he’d already completed a number of accomplished works. He was also very interested, at this time in his career, in the relationships between characters in his paintings. Within a few years he would paint ‘Interior scene (the rape)’ (c1870), a powerful psychological study of ‘disconnection’, and, a closer parallel to the Bellilli picture, ‘Sulking’ (1870).

The truth is that the ‘unconnectedness’ of the figures in Degas’ painting mirrors faithfully the deeply unhappy emotional weather in the Bellilli family house. The relationship between Laura and Gennaro – they’d married in 1842 – was under great strain. Another of Degas’ uncles wrote, ‘The domestic life of the family in Florence is a source of unhappiness for us. As I predicted, one of them is very much at fault and our sister a little, too’. In a letter Laura called her husband ‘immensely disagreeable and dishonest… living with Gennaro, whose detestable nature you know and who has no serious occupation, shall soon lead me to the grave’. When Degas returned to Paris she wrote to him, ‘You must be very happy to be with your family again, instead of being in the presence of a sad face like mine and a disagreeable one like my husband’s’.

The dominant figure in the painting is not the husband, but Laura. She’s dressed all in black, in mourning for her recently dead father, Hilaire (a portrait of him, by Degas, hangs on the wall behind her). Her dark hair is combed back and she stares out, her face severe, statuesque and expressionless, towards some unseen object beyond the right edge of the canvas. The only other parts of her body that are visible are her hands (Degas paid special attention to them in his studies for the painting). One rests protectively on the right shoulder of Giovanna, her elder daughter. The long fingers of her other hand touch the surface of a small table alongside her, as if to anchor herself physically – she’s pregnant with a third child, who will die in infancy – and emotionally.

The two children are dressed similarly. Their triangular white aprons or pinafores offer the only real prolonged passages of light in the painting. Giovanna stands in front of her mother, and is the only one of the four figures who faces the artist direct. She clasps her hands in a self-contained way, and shares her mother’s unrevealing gaze: maybe she’s already damaged by her parents’ hostilities. Her sister Guilia sits on a chair in the centre of the picture. She’s a freer spirit: her stance is both assertive (she holds her hands akimbo) and more relaxed (one leg is held back), as if she’s detaching herself from the gloom around her. (There’s a non-human figure in the picture, by the way: at the bottom left is (half of) the family dog, apparently eager to escape the scene.)

And on the right is the father, barely noticed when you first look at the painting. The armchair he’s sitting on is turned against us. Only part of him is visible: the thick armour of his beige jacket, and his balding, bearded head – in profile so that we miss any expression he may have. His left hand looks as if it’s firmly clenched, on the arm of the chair. He’s not looking at his wife and daughters. Instead, he seems to be unnaturally absorbed by some correspondence on the table beside him. Degas uses a vertical line – the left edge of the mirror, the mantelpiece support, the table leg and the chair leg – to mark off Gennaro’s isolation from his family. You might almost say all four figures are imprisoned by the strict framework of horizontals and verticals of the picture’s forms.

Above Gennaro is a mantlepiece cluttered with a large, ornate clock, a candlestick and plates, and a big mirror. The clutter is amplified by reflections in the mirror: a chandelier, a painting and what seems to be another mirror. All this busyness and distraction in the upper right of the canvas are in strong contrast to the pictorial and emotional plainness – even bleakness – on the left side.

‘The Bellilli family’ is the first work in which Degas brought the different elements of his painting concerns to perfection. Its taut, audacious composition, its colour choices (Arctic white for the dresses, ice-cold blue for the wallpaper) and its complex emotional tension mark it out as a key work of nineteenth century painting: as Laura Cumming calls it, ‘a novel in paint’. She has a brilliant phrase to describe the Bellilli family as caught by Degas, where everyone is present but nobody is actually looking at anyone: ‘a performance of unity betrayed by aversion’.

Leave a Reply