Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin may have reached the surface of the moon fifty years ago this week. But William Blake beat them to it, by 176 years. What’s more, he had no use for the sophisticated technologies of the Apollo 11 mission. All he needed was a long ladder. It’s easy for us, in our own despairing times, to forget that 1793 was a time of ambition and hope, and almost anything was then possible.

We know about Blake’s moon plans from a plate in one of his earliest ‘illustrated books’, a small collection of engraved pictures, with captions, which he called For children: the gates of paradise. It’s not one of his best-known works, but it occupies a critical chronological space between two of his most famous books, Songs of innocence (1789) and Songs of experience (1794).

The gates of paradise was a small book in two senses: its dimensions were tiny – each sheet is at most 95 x 63 mm– and Blake seems to have printed only a very few copies. Only five copies survive and Peter Ackroyd, one of his most recent biographers, reckons there may have been only a few more originally. But its scope was far from small – no less than the human journey from birth to grave. And though Ackroyd calls it ‘a kind of child’s primer’ it’s really no such thing. From its publication its precise meanings have defeated generations of adults, let alone children. (To be fair, Blake tended to see children as more open to the possibilities of understanding than adults, caught in the shackles of rationality.)

Blake himself seems to have regarded the book as more than a passing trifle. He carefully kept the copper plates, and reused them for a ‘second edition’ of the pictures, much later, in or around 1820, under a new title, For the sexes: the gates of paradise, with three additional plates, and some verses.

Each of the sixteen plates in the 1793 edition has an engraved picture, and beneath it a caption: a title and/or a quotation or ‘explanatory’ phrase. This format deliberately echoes (and enigmatises) that of the emblem book, a traditional and popular type of publication since the sixteenth century that used woodcut or engraved images and short accompanying texts to put across a moral lesson. The frontispiece and plate 1 start with two forms of how human life might begin: as a ‘chrysalis’ on an oak, and as a small body uprooted from the soil. In ‘Water’ (plate 2), ‘Earth’ (plate 3), ‘Air’ (plate 3) and ‘Fire’ (plate 4) the child has grown into the suffering and tormented man. Many of the other pictures are similarly unlikely as ‘gates to paradise’.

Some of the images have forbears in earlier emblem books, and in Blake’s own work, but Plate 9 is without parallel in either. It shows a night sky with stars, and a figure about to start climbing a long ladder that leads from the surface of the bare earth to a crescent moon. Watching are two other figures, a man and a woman standing close together – the figure’s parents, or possibly two lovers. The caption below reads, ‘I want! I want!’, and below is the ‘imprint’, found on most of the plates, ‘Pubd by WBlake 17 May 1793’.

As with many of the other plates this one is enigmatic. Does the figure represent spiritual energy and ambition – an attempt to escape from the oppressive gravity of the corporeal world to reach another, purer world? That would be an entirely Blakean view. Taken together the plates of the book hardly suggest that paradise is to be found in the earthly world.

But the caption ‘I want! I want!’ adds a different note. Then, as now, ‘I want’ is the cry of the small child demanding to get its hands on a new toy or other novelty, perhaps in the face of parental prohibition. Could the desire to climb to the moon stand for acquisitiveness, the soul-destroying urge to possess more and more, to master (in both senses, understanding and colonising) more and more of the universe around us? That interpretation would also be consistent with Blake’s stand against what he saw as the destructive effects of the scientific and rationalising revolutions of his age.

The moon, then, is just another gaudy, worthless prize. You’re reminded of the fact that the 1969 moon landing was not primarily a high-minded journey ‘in peace for all mankind’, in Neil Armstrong’s phrase, but a direct result of J.F. Kennedy’s determination in 1961 to overtake the Soviet Union’s lead in the Cold War space race and claim earth’s satellite in the name of (and with the flag of) God’s Own Country.

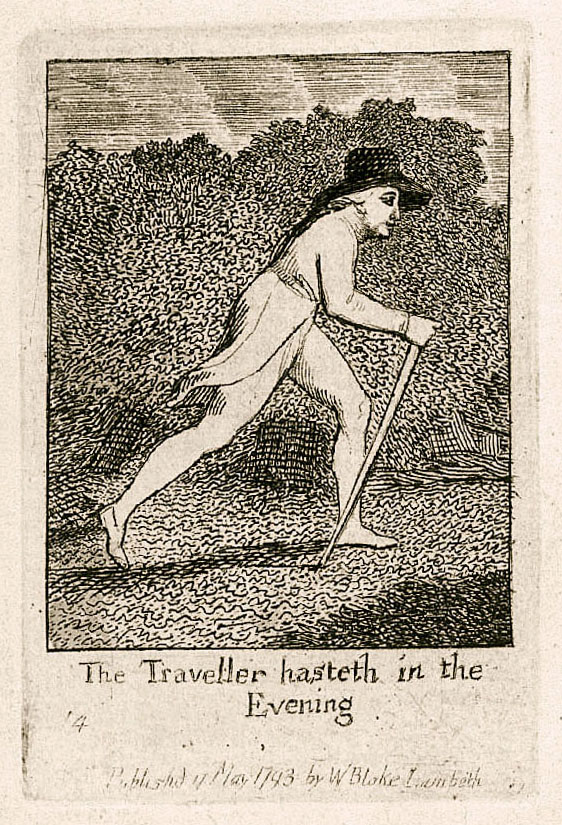

Whatever Blake’s intention (if he had a single intention), the remaining plates concern themselves with death and preparing for it. Maybe the finest of them is a figure Blake used many time in his iconography, plate 14, ‘The traveller hasteth in the evening’: a lone man with a broad hat, flowing long coat and staff, striding energetically along a road against a headwind. This could be Blake himself: liberated from the illusions of the sublunary world and hurrying towards a better one.

Leave a Reply