I first came across the name Rhys Trimble last month while wandering down a narrow lane from the castle to the main street in Denbigh. At the bottom of Lôn Brombil (Broomhill Lane) a poem by him, ‘Moliant i Ddinbych’, is painted on the wall of a building. It begins ‘Boreon Dafydd; o ael bryn dyfai: Lôn Brombil, grombil gandryll gaerau’.

When I got home I found that in 2015 Rhys had published a book in English (mainly; there’s also much in Welsh) called Swansea automatic. Always on the lookout for Swansea literature, I ordered a copy from the publisher, Aquifer Books of Llangattock.

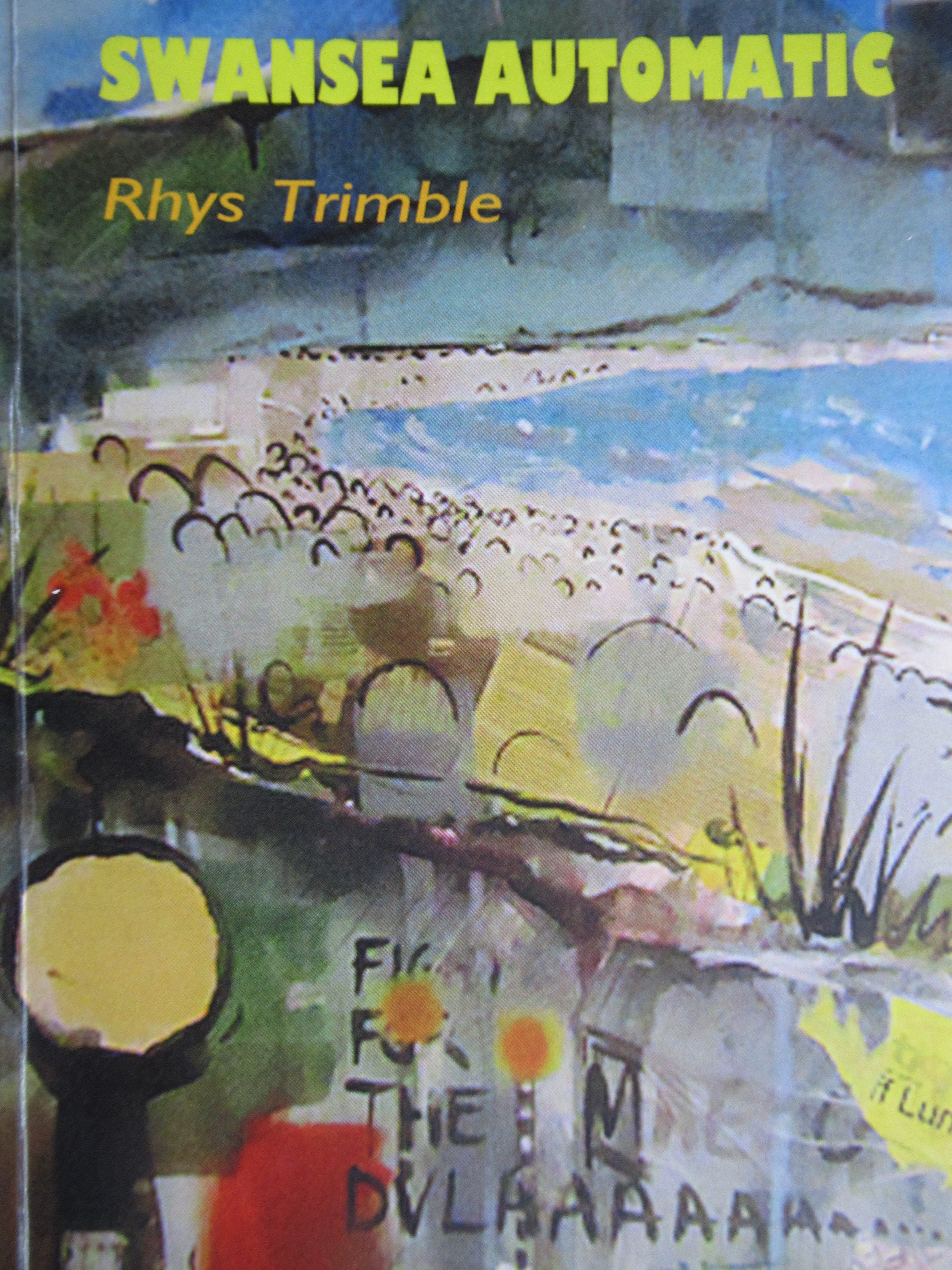

It’s a small pocket-size book of 132 pages, well printed in a serif type on coated paper. On the cover is a detail from a lively painting of Swansea Bay by Rhys’s brother Teilo. The book’s subtitle is ‘a creative writing manual’, but really it’s more of an exercise book than a manual. Rhys’s method is to put into practice the guidelines laid out by Bernadette Mayer and other members of the L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E postmodern poetry movement active in the US in the 1970s – the original guidelines or ‘experiments’ of 1978 are reproduced in an appendix.

Here’s an example. One guideline reads, ‘Get a group of words (make a list or select at random), then form these words (only) into a piece of writing – whatever the words allow. Let them demand their own form …’ And this is Rhys’s worked example:

say simple

job lamb

black to

misunderstood of

dog at

pink crystal

mint green

moxie landlord

say pink at dog misunderstood – simple lamb landlord to moxie mint, green, crystal job at black.

or

misunderstood moxie, green dog, pink crystal job misunderstood, say black to lamb at “mint” – simple landlord.

The running joke is that these attempts always fall short of being satisfactory. Much of the book is taken up with the various ways they fail. The realities of the external world, the interior state of the author (often precarious), and the complex metaphysics of expression are always intruding on the exercise. (This is lucky, because the L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E people are extreme formalists for whom ‘connotation’ and meaning are anathema, and Swansea automatic would have been an arid read if Rhys had obeyed their orders.)

Rhys’s ‘exercise book’ is real: a cheap one, with five sections, orange, pink, yellow, green and blue. Swansea automatic’s chapters bear the names of the same five colours. They possess various ‘connotations’, contrary to L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E doctrine. The ‘writing’ of the book is multi-layered. Some material is recorded on tape (then transcribed); a ‘wooden pen’ feeds the exercise book with words; the whole is keyed in to appear on screen; and the final text appears in print. Rhys has much fun playing with this palimpsest.

Swansea automatic also moves through time and space. In fact, it’s in part a picaresque novel, with several changes of scene and a lengthy cast of characters, human and canine, living and dead, and mythical. The dead include Pwyll prince of Dyfed and his alter ego Arawn lord of Annwn, B.S. Johnson, W.G. Sebald and Yevgeny Yevtushenko. Rhys’s thoughts, memories, references, exercises and encounters are threaded together using swift mental jumps and that loosest of syntactical connectors, the em or dash. He blames Emily Dickinson for an addiction to it, though the granddaddy of the em was surely Laurence Sterne, who strangely never gets a mention.

Rhys starts in north Wales, on an Eliotic note,

“I had never heard that bell strike before” – the clocktower, Bangor, Gwynedd.

before taking the bus to Aberystwyth and Swansea. The pink chapter takes us on a psychic tour of Swansea and environs: the abandoned astronomical observatory, bronzed Dylan Thomas, Tesco, Swansea Jack the dog, the SA1 tower, the prom ‘fitness trail’, the old Vetch Field. Later we find ourselves in Newport, and then back in north Wales. By the last page we’ve reached Bethesda, and Rhys finally manages to throw aside the language games, and despite himself gives way to a lyricism the US poets surely wouldn’t approve of:

& under the moon

PESDA – lleuad –

moon dog town – I meet

another travelleur – reader of Caradog Pritchard –

[UN NOS OLA LEUAD – BETHESDA NOVEL – ONE MOONLIT NIGHT]

“Rhannu ddeigryn o dan y lleuad”

Mei & I stop & double up on loner status –

night ping –

pinball – impets

“Cwm lloer”

“Radiance”

“Bwyd & Gwely”

“Hwyl Mêt”

Though it never leaves its cheap spiral-bound notebook, Automatic Swansea takes us on a headlong journey through Rhys’s well-stocked, bilingual mind. Personally I’d have preferred it if he’d kept the language (and all his ludic skills) but jettisoned the L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E. And – this is me being selfish – if he’d stayed in Swansea a lot longer, to excavate the mysteries of the city and its people. Swansea is still to find its new mythographer, who will save us from the endless recycling of Dylan Thomas.

The presiding genius of Automatic Swansea is B.S. Johnson, the novelist who was sure that writing fiction was no longer possible. It’s good to be reminded of that writer’s mix of linguistic ingenuity and deep feeling, and of the connection with Wales which meant so much to him. Rhys’s epigraph is Johnson’s poem ‘Porth Ceiriad Bay’, and there are mentions in the text of the ‘book in a box’ The unfortunates, a more radical formal experiment than the US poets could manage, and See the old lady decently. Loss was one of the main drivers of Johnson’s work. After an overnight stay at Gregynog recently I sought out his short recollection of his time there as a Gregynog Fellow in 1970. This anecdote, about using Gregynog’s printing press, echoes Rhys’s concern with typographic detail. It offers a small but perfect example of Johnsonian loss, in this case loss of language:

In partnership we [the poet Philip Pacey and BSJ] evolved a project which was so breathtaking that I would never have attempted it on my own: an eight-page sheet folded to four printed sides devoted to one each of our poems, a title page, and a credits page. Furthermore, such was our hubris, this was to be an edition of no less than twenty copies and was to be on green-tinted paper of an unknown dampening quality.

It was inevitable that such effrontery would be punished. It was the nineteenth when I noticed that (on the title page, too) the second O of my surname was not in the same font as the first O. Since this is a scholarly journal in which only the truth may be told, it must be recorded that it was Philip who set the title page; and he had not, by several days, as much typesetting experience as I had, of recognising the faces, the bodies, the Os. It is also probably necessary to state that we were not under the influence of alcohol at the time, neither Philip at the time of setting nor myself at the time of not noticing during machining. As if it were relevant.

At the time, it did not seem to me to make a curiosity of the edition; it made a cock-up of it.

But there was no time to start again. We both signed the edition, and divided it equally between us; the chances of its being held against us we were prepared to accept.

B.S. Johnson, Well done God! Selected prose and drama of B.S. Johnson, edited by Jonathan Coe, Philip Tew & Julia Jordan, London: Picador, 2013, p. 451-2.

Leave a Reply