False news is now so natural a part of our world that few people are surprised to read about the deaths of people who remain stubbornly alive. There are plenty of examples, many of them recent. Wikipedia lists over 300 in one of its more amusing pages, List of premature obituaries.

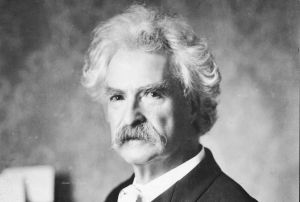

The ‘reported death’ people tend to remember is Mark Twain’s. In 1897 some thought he was dead, though no obituary actually appeared. His response was ‘the report of my death was an exaggeration’ (rather than the one we remember, ‘the rumours of my death have been greatly exaggerated’). The unfortunate Twain suffered the same fate in 1907, when his yacht went missing and the New York Times reported him dead. He wrote an article for the paper to announce his return from the dead:

You can assure my Virginia friends, said he, that I will make an exhaustive investigation of this report that I have been lost at sea. If there is any foundation for the report, I will at once apprise the anxious public. I sincerely hope that there is no foundation for the report, and I also hope that judgment will be suspended until I ascertain the true state of affairs.

My favourite undeath is that of Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Coleridge was once in an inn, according to one account, when he heard a man reading aloud a newspaper report of his death. He asked to see the article, which reported, ‘it was very extraordinary that Coleridge the poet should have hanged himself just after the success of his play [Remorse]; but he was always a strange mad fellow’. Coleridge replied: ‘Indeed, sir, it is a most extraordinary thing that he should have hanged himself, be the subject of an inquest, and yet that he should at this moment be speaking to you’. The poor suicide, it seems, was wearing a lost shirt, marked ‘S.T. Coleridge’.

Some falsely reported deaths are sadder still. The writer Jean Rhys disappeared without trace after publishing several highly regarded but not popular novels in the 1920s and 1930s. It was assumed that she’d died during the Second World War, or drowned herself in the Seine, or drunk herself to death, or perished in a sanitorium. She was finally tracked down in 1949 to a small house in Cornwall by the BBC, when they were planning an adaptation of her 1939 novel, Good morning, midnight.

It was not a good time for Rhys. Her third husband, Max Hamer, was imprisoned for fraud, and she was destitute and drinking heavily. But, encouraged by the writer Francis Wyndham, an admirer of her pre-War novels, and later by the agent for André Deutsch, Diana Athill, she continued work on a new novel she’d started. She was a perfectionist, and couldn’t let the book go. Finally, in March 1966, Rhys wrote to Athill,

I’ve dreamt several times that I was going to have a baby – then I woke with relief. Finally I dreamt that I was looking at the baby in a cradle – such a puny weak thing. So the book must be finished, and that must be what I think about it really. I don’t dream about it any ore.

Wide Sargasso Sea was published later that year. It was received almost immediately as a masterpiece of post-colonial literature, its extreme emotionalism held within a precise style and a tight structure. The book’s proceeds allowed her to live more comfortably for the remainder of her life, helped by a ‘Jean Committee’ of carers, including Wyndham, Athill and Sonia Orwell. But, ‘it has come too late’ was her bitter reaction to recognition. She was 76 years old when the book appeared. She published an ‘unfinished autobiography’, but no other novels followed.

She was also quoted as saying, ‘If I could choose, I would rather be happy than write’. Her life had more than a share of unhappiness. She has born, Ella Gwendolen Rees Williams, in 1890 on the small Caribbean island of Dominica, the daughter of a Welsh doctor, William Rees (or Rhys) Williams, and a Creole mother. She felt at home in neither community, black or white, but at the age of sixteen she left the luxuriant, vivid and extreme landscape of the island for England. Here she was mocked and bullied in school for her colonial background and her West Indian accent. As a young adult she led a wandering, ramshackle existence in London, Paris and elsewhere, working as a chorus girl, model, prostitute and mistress. She was prone to periods of depression and excessive drinking. In 1924 she met the novelist Ford Madox Ford in Paris, who encouraged her to write, and she worked hard on her own novels. Her second husband gave her a copy of Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre, and instantly she conceived the idea of writing the story of Mrs Rochester, the ‘madwoman in the attic’ of Thornfield Hall, whom Rochester had married in the Caribbean.

When you read Diana Athill’s account of Rhys in her memoir Stet, and of her account of Dominica and its colonial inheritance, you begin to understand why Bertha Rochester – Antoinette Cosway was her original name – appealed so much to her. The two young women shared a common early experience – of being wrenched from a very small community, scarred by historic slavery and colonial exploitation, and replanted in a cold, alien land they’d known before only from stereotypes. Part 1 of Wide Sargasso Sea is Antoinette’s narrative, where Jamaica, her first home, and the unnamed ‘honeymoon island’, are part-paradise and part-hell, full of incomprehensible cruelties meted out to her mother and herself. Part 2 is narrated mainly by Rochester (though he is never named), who has ‘acquired’ Antoinette for her money but who cannot love her, and is himself driven half mad by her. The final section is set in Thornfield, where he keeps Antoinette in ‘social isolation’: the wild dreams she describes recall the flame trees of her childhood and anticipate the disastrous fire of Jane Eyre, and her own death.

There are many themes of Rhys’s book – the violence of colonialism and racism, the power of fear, the ‘uncanny’ and past secrets, the remoteness of the possibility of love – but a strong one is that of the ‘premature death’. Antoinette’s mother, driven from their Jamaican home by hatred and arson, has already died once, says Antoinette to Rochester, before she remarries and starts a new, even more painful life:

‘Is your mother alive?’

‘No, she is dead, she died.’

‘When?’

‘Not long ago.’

‘Then why did you tell me that she died when you were a child?’

‘Because they told me to say so and because it is true. She did die when I was a child. There were always two deaths, the real one and the one people know about.’

Antoinette herself suffers two deaths. Her removal from her homeland and her imprisonment by Rochester in England is for her a half-life after the death of the self. Her sense of identity has eroded – has been deliberately destroyed, if we believe the evidence of Jean Rhys – to almost nothing:

There is no looking-glass here and I don’t know what I am like now. I remember watching myself brush my hair and how my eyes looked back at me. The girl I saw was myself yet not quite myself. Long ago when I was a child and very lonely I tried to kiss her. But the glass was between us – hard, cold and misted over with my breath. Now they have taken everything away. What am I doing in this place and who am I?

Jean Rhys, too, could look back on two lives. More than two, really, because she ‘died’ three times and lived four different lives. Her years in Dominica, vivid and indelible, fed directly into Wide Sargasso Sea. In her youth and middle years in Europe she was always on the move, living from hand to mouth but devoted to her craft as an author. When she ‘disappeared’ after the War she scraped an obscure living in Cornwall and Devon. And then, in the wake of the publication of Wide Sargasso Sea, came the final period of recognition and comparative ease, until her final death, in 1979.

Leave a Reply