One of the very few consolations of Covid lockdowns has been that more people seem to have read more books during 2020. In the first half of the year fewer print books were sold, since bookshops were often closed, but UK sales of e-books increased by 17%, and audio books by 47%. I’ve certainly read more – and probably more widely – than ever. Here are a few that were specially enjoyable. (I’ve excluded books I’ve written about already in 2020.)

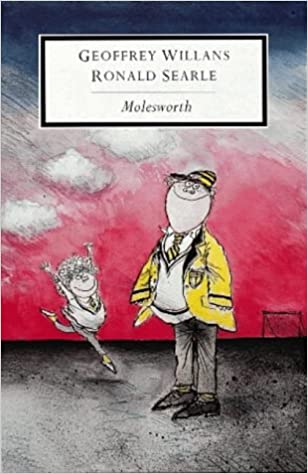

Geoffrey Willans and Ronald Searle, Molesworth

Four books in one, republished by Penguin as a Modern Classic: Down with skool (1953), How to be topp (1954), Whizz for atoms (1956) and Back in the jug agane (1959). If you want to understand what moulded the minds of the public school gangsters current terrorising the UK, you needn’t look further than these utterly cynical classics. Nigel Molesworth, poor speller but expert satirist, tells us about life in his 1950s prep school, St Custards. His fellow inmates include Grabber, ‘head of school captane of everything’, Peason ‘my grate frend’, and fotherington-thomas (‘hello clouds, hello sky’). It’s a world where self-protection and self-advancement come first, nothing is taken seriously and chaos is welcome: ‘in fact any skool is a bit of a shambles’. Like the Tory MPs they will grow into, the boys are divided into Cads, Oiks, Goody-Goodies and Bulies. Molesworth himself, a facetious twister with no respect for the truth or anyone but himself, is clearly Boris Johnson in vitro. His final words are ‘perhaps there will be room in the world for a huge lout with o branes. In which case i mite still get a knighthood.’ What a pity Ronald Searle isn’t still with us, to pickle in his acid cartoons the ‘adult’ monsters the louts have become.

Bernadine Evaristo, Girl, woman, other

This won the Booker Prize in 2019 – late recognition for the author of a succession of excellent and very different novels (my favourite is The emperor’s babe, a novel in verse set in the Roman Empire). Girl, woman, other opens a window into the lives of twelve black women in contemporary London. Not as victims or oppressed people, but as bold women with energy, confidence and staying power. They wander in and out of one another’s stories, biffing people who stand in their way. Amma, the first of the twelve, is a dramatist whose latest play is about to open at the National Theatre. She’s worked her way up from the fringe (in all senses), working in tandem with her partner Dominique, who has since left for America. We hear about her turbulent past, in part through the eyes of her daughter Yazz. This ‘back-fill’ kind of narration, which Evaristo uses for other characters, employs a style that initially feels confusing but which washes over you with astonishing fluidity and carries you along easily through over 400 pages. This novel is a perfect antidote to Covid dread.

Peter Lord, Looking out

A new collection of essays on Welsh artists of the past by Peter Lord. They read like offcuts from his earlier research on nineteenth and twentieth century Welsh art, crystallised in his magisterial Visual culture of Wales series. The subtitle, ‘Welsh painting, social class and international context’, signals that the focus, as you’d expect from Peter, will be on the sociological import of the works he discusses rather than on their artistic character. My advice would be to skip the introduction – a little of Peter’s polemicising goes a long way – and dive into the essays, all of which open fresh views on a wide variety of painters. To start with, Victorian portraitist Evan Williams, a trio of itinerant artisan painters, also portraitists, and Edgar Herbert Thomas (an artist new to me, who produced some interesting landscapes and still lives). Then there’s an excellent dissection of the bizarre neo-medieval dreams of Howard de Walden of Chirk Castle and his circle, and an extended and critical (in both senses) treatment of the work of M.E. Eldridge, especially her mural sequence The dance of life. The final essay, starting from a discussion of ‘funeral paintings’, asks why Victorian painters in Wales were so reluctant to embrace social realism and points the finger at the stifling effect of rigid nonconformist piety. Interesting questions are asked, too, about the mining paintings of Josef Herman.

This is a handsome book, produced by Parthian. The reproduction of the works illustrated is outstanding.

John Davies, Fy hanes i: hunangofiant

This autobiography was published in 2014, a year before its author/subject’s death. I bought my copy in that excellent bookshop Siop Pen’rallt in Machynlleth in April 2017, and it’s been waiting its turn to be read since then. The title nods in the direction of John Davies’ magnum opus Hanes Cymru (1994). I didn’t know him well, and always felt rather in awe of him, or rather his erudition and vast store of anecdotes. There’s plenty of both in the book. John Davies was unusual in being a bridge between Welsh-speaking and non-Welsh-speaking Wales, and between rural and urban Wales: Bwlch-llan, his distinguishing sobriquet, is in the depths of the Ceredigion countryside, but his first home was Treorchy and his last was Grangetown, Cardiff. And he was unusually cosmopolitan, having travelled extensively in most parts of the world: there are many stories of overseas adventures here. Fy hanes i is full of wit and humour, but it also carries a note of sadness: it’s a book of farewell. As always with John Davies, it’s written in a polished, slightly formal style that’s becoming rarer now. (An English translation by Jon Gower was published in 2015.)

Raymond Antrobus, The Perseverance

Raymond Antrobus, a young English poet of Jamaican origin, is deaf. Those of us who are not usually give little thought to the experience of not hearing the world, and many of these poems, like the opening one, ‘Echo’, surprise you with the freshness and assertiveness of their vision:

My ear amps whistle as if singing

to Echo, Goddess of Noise,

the ravelled knot of tongues,

of blaring birds, consonant crumbs

of dull doorbells, sounds swamped

in my misty hearing aid tubes

Other poems deal with racial identity and Antrobus’s family, especially his father. ‘The Perseverance’ is a memory of waiting outside a pub of that name for his father to come out, as it gets dark amid the noise of the drinkers within (‘we lose our fathers before we know it / I am still outside THE PERSEVERANCE, listening for the laughter’). Another poem, a sad elegy, is entitled ‘Thinking of Dad’s dick’. This book won several prizes after it appeared in 2018. Its colloquial language and wide frame of reference make for a great mix.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Notebooks: a selection

For research purposes I’ve spent many hours in 2020 in Coleridge’s company, and the more I read him (and about him) the more intriguing he seems – unlike Wordsworth, a bore whom I’ve disliked ever since we had him pushed down our throats for O Level in 1966. While Wordsworth plods, Coleridge darts. He’s interested in everything: politics, landscape, philosophy, children’s language, the way his mind works, food, dreams, theology. He’s always promising projects he won’t deliver, and when he does start one he often fails to finish it (an example being ‘Kublai Khan’). His notebooks – he carried a notebook with him throughout his adult life – are a big, bulgy sack of his passing thoughts. I find the best way to read them is on a diet of one a day, because so many of the entries need thought to digest them. There are extended pieces, in the early years on nature and landscape, later on philosophy and theology, but others are brief, lapidary and startling in their new use of language. Here’s a selection from the selection:

169. No one can leap over his Shadow / Poets leap over Death.

184. The yellow Hammer sings like one working on steel, or the file in a Brazier’s Shop.

186. The Thrush Gurgling, quavering, shooting forth long notes. Then with short emissions as if pushing up against a stream.

210. Body & soul, an utterly absolute mawwallop.

217. Memory carried on by the fear of forgetting / thus writing a thing down rids the mind of it.

229. My words & actions imaged on his mind, distorted & snaky as the Boatman’s Oar reflected in the Lake.

Eley Williams, The liar’s dictionary

This is a wordy novel for lovers of words. Its two characters live over a hundred years apart but work on the same (apparently) unending project, the making of Swansby’s new encyclopaedic dictionary. Peter Winceworth, a painfully introverted lexicographer, hits on a new idea. ‘For some years now, just to pass the time and for his own amusement, he had been making up some words and definitions’. Now he decides to start inserting them surreptitiously into the dictionary. Meanwhile, Mallory, a present-day intern, is given the job of unmasking these false insertions or ‘mountweazels’ that are known to lie in the text. The two chronologically separated narratives are interleaved, until they come together at the end – which, perhaps not surprisingly, is incendiary. Eley Williams’s previous book of short stories, Attrib., is shot through with a love of the metaphysical complexities of language, and her first novel is a sustained riff on how words define us – and ruin us.

From the novel’s preface: ‘In some even quite modern dictionaries, if you look up the word giraffe it ends its entry with [SEE: cameleopard]. If you look up cameleopard it says [SEE: giraffe].’ I used the same logocyclical device in the index to my own novel.

Richard Ovenden, Burning the books

In our new dark age, when fakery, the short attention span and elective ignorance are banishing knowledge and enlightenment to the outer suburbs of human life, there couldn’t be a better time for a book about the destruction of libraries and archives. Burning the books has been widely and rightly praised. Richard Ovenden, the director of the Bodleian Library, gives us well-researched case studies of destructions (and some salvations), across time and space from ancient Assyria to the present day. Unsurprisingly, the most chilling chapter concerns the Nazi book burnings of 1933, a portent of what was to follow, as Heinrich Heine foretold over a hundred years before. Nowadays, sudden destruction is rarer – though who would assert that Sarajevo’s national library will the last to be set alight? – and powerful philistines prefer to strangle libraries slowly by cutting off their funding. Only the other day the leader of Walsall Council asked of his own public library, ‘do we really need it?’. The National Library of Wales has been so weakened it can barely fulfil its remit. Ovenden is right to draw attention to Facebook, Google, Amazon and other global monopolies, false friends to the public interest, who now effectively control most contemporary (digital) knowledge. His solution, a ‘memory tax’ on the companies, with the proceeds directed to public memory institutions, is an attractive one – though unlikely to be realised in today’s ideological climate.

Leave a Reply