Our school was just across the road. I could have left our little brick house, Corton Cottage, at one minute to nine and still have been in time for lessons. The school building was small, built of warm stone, and handsome in its modest way. It dated back to the 1860s. At first not much more than a single large room, it gained an extension at the back. The infants occupied the extension, the juniors had the original building.

Its name was Hoylandswaine County Primary School. There were about sixty or seventy pupils at that time. Very few of the pupils were brought by car. Nearly everyone walked, mainly in a straggling procession down Haigh Lane, the steep road from the village, half a mile away.

Miss Jackson taught the infants. She was a reticent, sympathetic person, who wore soft cardigans and a ready smile; everyone liked her. When we were old enough, we moved next door, to Miss Hinchcliffe’s care. She was quite different, stern and formidable, and gave us no chance to misbehave. I don’t remember any physical punishments, though Mr Stephenson, a mild-mannered retired steelworker who lived with his wife next door to us, in School House – presumably it had once been the schoolteacher’s home – used to say how he had been caned regularly when he was a pupil there before the War. My mother seemed to get on well with Miss Hinchcliffe, and we would sometimes go, reluctantly in my case, to visit her home in Oxspring. She lived there with her brother Sydney, who owned or managed a small wire mill, Winterbottom’s Wire Drawers, next door to their house, down in the valley of the river Don. I think the real reason for the visits was so that my mother wanted to see Miss Hinchcliffe’s dahlias. She grew them in large quantities and varieties, and put the best of them into shows to compete for prizes. (My mother never had much luck with dahlias, and in any case, as a good Scot, preferred her heathers.)

My memory is of the school as a happy place. Lessons were formal and probably old-fashioned – although at the time the West Riding was known for its educational progressiveness under the leadership of its director of education, Sir Alec Clegg. All we had to play in was the small tarmac playground at the back of the infants’ block – later the school bought a big field in addition – but we played keenly. Always useless at games, I found a niche in rounders, with an occasional talent for hitting the ball across the wall into Cross Lane.

My favourite time in school, though, was the end of Friday afternoon, when there were no lessons, and Miss Hinchcliffe would get out a book and read to the whole class. With the right book she could command complete attention. We would sit in silence, wholly absorbed in the distant world of the book, transported far away from our tiny village world.

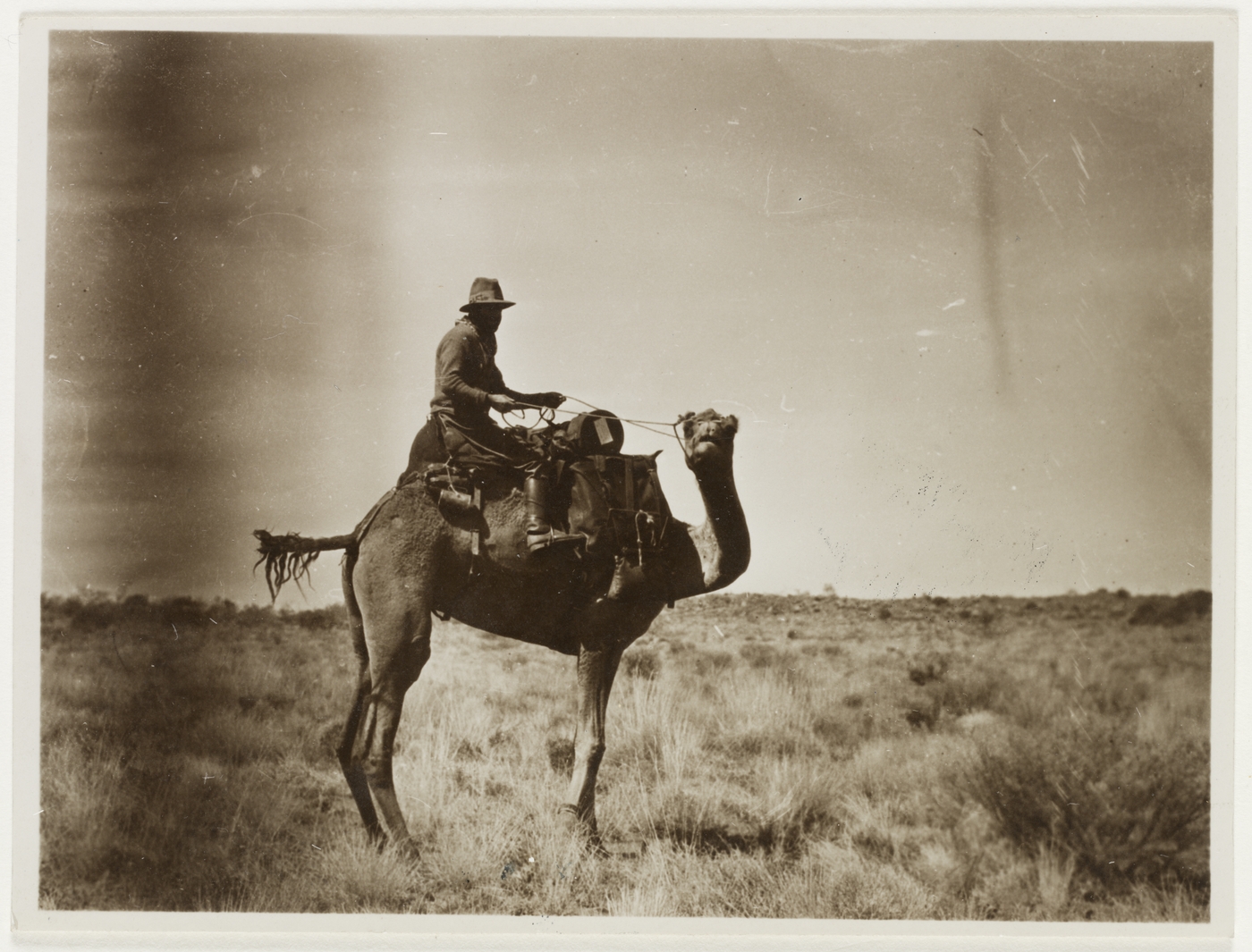

The book I most remember, of all of ones Miss Hinchcliffe read, was a story that will be unfamiliar to almost everyone outside Australia. Its title was Lasseter’s last ride. As a child I didn’t know the author’s name, but now I know it was Ion Llewellyn Idriess. His novel was an adventure tale, about a gold prospector who goes missing in the centre of Australia, and what most intrigued me was that Lasseter’s story was supposedly pieced together from the letters he hid in the ashes of his successive camp fires as he attempted to find his gold reef and to survive the harsh conditions of the outback. The letters were later found by men sent to trace him. They tracked him from camp fire to camp fire, until they came across his dead body.

Harold Lasseter, I found much later, was a real person, born in Victoria in 1880. During the Great War he succeeded twice in avoiding being send overseas to battle. In 1929 he came to prominence by claiming to have discovered, and then lost the location of, a huge gold reef in the centre of the country. The next year he joined a party that tried to find ‘Lasseter’s Reef’, but he became detached from the rest. His body was found in March 1931 by a bushman called Bob Buck, and may eventually have been buried in Alice Springs. Neither Lasseter nor Buck seems to have been entirely reliable people, and the entire story is a uncertain mix of fact and fantasy. No great gold reef ever came to light, even though searches were made frequently, most recently in 2013.

Lasseter’s story was an ideal and topical subject for Idriess’s novel, which proved a popular success when it was published later in 1931. Idriess had a Welsh father who had emigrated to Australia. He worked as a ‘rabbit poisoner, boundary rider and drover’ before becoming a prospector, with the help of the Aboriginal inhabitants of northern Australia, and then a best-selling writer. After publishing Lasseter’s last ride, he wrote at least one book a year until 1964.

I was enchanted as I listened to this book. I loved its theme of quest, its remote, arid locations, its solitary adventurer, the help Aborigines gave him and their apparent curse on him, the detection of the camp fire letters, and Lasseter’s poignant end. The story stayed with me, and over the years it would come back to me, especially when the Australian outback was mentioned.

A few years ago it occurred to me that I might get hold of a copy of the book. And so I did. A good second-hand copy arrived through the post, and I fully intended to read it. But then I had second thoughts. What if the novel failed to give me the same intense pleasure it had when Miss Hinchliffe read it to us fifty years ago? What if it turned out to be badly plotted, or badly written? Would I find the novel’s racism too much to take? What if I had misremembered the story? Would that throw into question the veracity of my other memories, not just of the book, but also of Miss Hinchcliffe and my other experiences in Hoylandswaine School? Are these memories, or appearances of memories, too valuable to risk endangering?

I’m staring at the book as I write this. And I’m still not sure whether or not I should begin reading Chapter 1.

Leave a Reply