Another birthday, and I’m celebrating by throwing out yet more paper hoarded over the years. This time it includes a dark red ring-file containing notes and essays from my first-year university course in Classics. They’re written in handwriting it’s still quite easy to make out. (By contrast, my handwriting today, disabled by decades of keyboard typing, is unreadable after a day or two, once the memory of its writing has vanished.)

The notes are detailed and dense. I can only think that in 1970 the brain was sharper, the memory roomier, the mental energy more vigorous. Some of the pages summarise lectures by the greats of the period, like old Sir Denys Page, Regius Professor of Greek, a tall man with a forbidding face who would pace the stage of the Mill Street lecture theatre like an old-style Shakespearian actor, declaiming, for the hundredth time, on the tragedies of Sophocles. Then there was John Raven, chain-smoking his way through the Presocratics in his Saturday morning lectures, Moses Finley, drummed out of the US by Joseph McCarthy, and Pat Easterling (she taught me Aeschylus later on, and I felt very lucky).

At the end of some of the Greek literature essays, and occasionally in their margins, are tiny, thin scrawls written, mostly indecipherably, with a bright red pen. The first essay, on Sappho and Alcaeus, was evidently not a success. Several crimson question marks litter the margins. Later comes ‘I don’t follow’. At the end is the comment, ‘I think you should have tried to bring out more of the intense individuality of both poets, & their amazing ability to make poetry out of the simplest words & most ordinary experiences’.

‘The structure of an epinician ode of Pindar’ came back confettied with red ink. Five lines of comment at the end are completely illegible, but they don’t look complimentary. An essay on Oedipus Tyrranus wasn’t much better, and attracted just two short sentences, one of them an accusing question. Then, slowly, I seem to have improved. Or at least there are a few more approving, though laconic, remarks: ‘this is sound’, ‘good’. Finally, at the end of a long essay on Aristophanes’ Birds, one of my favourite plays, the single sentence, ‘This is an excellent account & very pleasantly written’. I must have left the room after that tutorial felling like I’d scored the winning goal in the World Cup final.

The red pen belonged to a long-retired Fellow called Henry Thomson Deas. I think he was a Scot. I don’t have a clear memory of his physical presence, (though a photo of him as a much younger man has come to light). He’d made his scholarly reputation in 1931 with a long article in Harvard Studies in Classical Philology entitled ‘The scholia vetera to Pindar’. Pindar was a famously and ferociously difficult Greek poet, known for his long hymns of praise to sporting celebrities. Deas was admired for his ingenuity in disentangling the ancient commentaries on these poems. After that, though, he seems to have suffered from writer’s block. He never completed a doctorate or published a book. In fact, he produced very little during the forty years between his moment of glory in 1931 and the year in which he taught me. Today, in these competitive university times, I don’t suppose he’d survive long.

The historian of the College mentions that Deas was on the losing, conservative side in an impenetrable academic civil war in the 1950s called the ‘Peasants’ Revolt’. After this he retreated from the corporate life of the College and the company of the Fellows. By the time I arrived as an undergraduate he was kept on for occasional teaching duties, old though he was, presumably because the College had a shortage of Classics teachers.

(Our Director of Studies was another ancient Fellow, Guy Griffith, a mild and amiable man from Sheffield, a researcher on the megalomaniac Alexander the Great. In his rooms in Tree Court he would lead us in enjoyable, sherry-laced seminars before dinner. Long before, in 1936, he’d published a book with the political philosopher Michael Oakeshott called A guide to the classics. I still have a copy. It has a brown cloth cover and the appearance of being a dull summary of Greek and Roman civilisation. It’s actually a lively primer on how to pick a winning horse in the Derby. It was said that no book was more widely read among the College’s Fellows.)

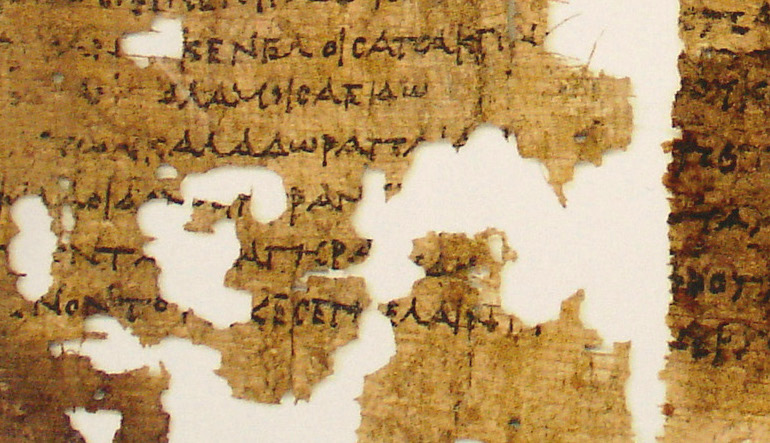

Mr Deas held his tutorials in a spartan room in a forgotten Victorian outpost of the College (he had no rooms there himself). I went along there, dressed in my ragged, third-hand undergraduate gown – Deas was a stickler for tradition – with little expectation of being enlightened. And indeed I don’t remember learning much from those encounters. For Deas, like most who taught Greek and Latin at the time, the study of literature was text-heavy and resolutely untheoretical, and he concentrated on explaining minutiae. (Denys Page, I remember, was similar: he would try to unravel the mysteries of Oedipus Tyrranus as if it were a classic-age English detective story – unsurprising, maybe, since in wartime he’d worked on codebreaking in Bletchley Park.)

Mr Deas held his tutorials in a spartan room in a forgotten Victorian outpost of the College (he had no rooms there himself). I went along there, dressed in my ragged, third-hand undergraduate gown – Deas was a stickler for tradition – with little expectation of being enlightened. And indeed I don’t remember learning much from those encounters. For Deas, like most who taught Greek and Latin at the time, the study of literature was text-heavy and resolutely untheoretical, and he concentrated on explaining minutiae. (Denys Page, I remember, was similar: he would try to unravel the mysteries of Oedipus Tyrranus as if it were a classic-age English detective story – unsurprising, maybe, since in wartime he’d worked on codebreaking in Bletchley Park.)

And yet, behind that dour façade and across the years of disappointment, Henry Deas still responded in an intense and instinctive way to the power of the Greek poets. Rereading the words he wrote in red on my essay about the language of Sappho, the most direct and thrilling of all ancient writers, I suddenly felt a warmth for the man, and a regret that I’d not taken full advantage of the long experience he had to offer.

Mr Deas died soon after he finished teaching me in summer 1971. But I’ll remember him a while longer, even as I take the red file of notes and essays in the car to the recycling centre. (The undergraduate gown’s going, too.)

Leave a Reply