1 Origins and foundations

1 Origins and foundations

The first local archaeological society in Wales, the Caerleon Antiquarian Association, was founded on 28th October 1847. It owed its existence largely to the efforts of one man, John Edward Lee (1).

Born in Hull in 1808, Lee worked from the age of sixteen in his uncles’ shipping office, but devoted his leisure hours to the study of science, especially geology and natural history. He was a member of the Royal Institution in Hull, and spent many hours at night arranging specimens in its museum. Suffering as a young man from ill health, he travelled widely on the Continent and developed a lasting interest in the history and antiquities of the countries he visited, which culminated in the publication in 1866 of his edited translation of Ferdinand Keller’s important work, Lake dwellings of Switzerland and other parts of Europe (2). His geological interests led to the accumulation of a fine collection of over 21,000 specimens, presented in 1885 to the British Museum.

Lee came to Caerleon in 1841, drawn, like many other Englishmen, by the opportunities offered to entrepreneurs by the industrial expansion of South Wales. He became a partner in the firm of J.J. Cordes & Co. of Newport, manufacturers of nails, spikes and rivets, and settled at The Priory, Caerleon, marrying in 1846. His services to the town were many, and included the provision of an adequate water supply (3). But the chief object of his interest proved to be the remains of the Roman fortress, within the walls of which The Priory lay, and it was not long before this interest was translated into action.

Lee came to Caerleon in 1841, drawn, like many other Englishmen, by the opportunities offered to entrepreneurs by the industrial expansion of South Wales. He became a partner in the firm of J.J. Cordes & Co. of Newport, manufacturers of nails, spikes and rivets, and settled at The Priory, Caerleon, marrying in 1846. His services to the town were many, and included the provision of an adequate water supply (3). But the chief object of his interest proved to be the remains of the Roman fortress, within the walls of which The Priory lay, and it was not long before this interest was translated into action.

Caerleon in the mid-nineteenth century was still a small town, with fewer than 1,500 inhabitants, but was expanding as a result of the growth of its larger neighbour, Newport. New discoveries of Roman remains were therefore constantly coming to light and entering the possession of private residents and landlords, but little effort was being made to record them or preserve newly exposed sites. Many antiquities had been lost, scattered or destroyed (4). Little had been published on Caerleon’s antiquities since Archdeacon William Coxe’s Historical tour in Monmouthshire of 1801.

Lee was determined to remedy this lamentable state of affairs. His first task was to record some of the Roman antiquities before they were lost or removed:

Under the circumstances, the few leisure hours which I possess have been studiously devoted to making accurate drawings of all the unpublished inscriptions, arid other antiquities, found either at Caerleon or in the neighbourhood.

Many of these drawings he then published in a book entitled Delineations of Roman antiquities found at Caerleon (the ancient Isca Silurum) and the neighbourhood, which appeared in 1845. Sixteen coloured plates depicted inscriptions, pottery, tiles, glass and small metal objects, all in the private collections of residents in or around Caerleon. Illustrations of coins were omitted, on the grounds that ‘these would have required more time, and, I may add, more knowledge of the subject, than I at present possess’ (7), but a complete catalogue of them, by Charles William King of Trinity College, Cambridge, was included. Anticipating objections that some of the items shown were of small size and little interest, Lee wrote

…my only apology must be an anxiety to give a copy of every pattern found at Caerleon, for the sake of comparison with those of other places. It is hoped, however, that if there should be a deficiency of interest in one department, it is amply made up in the others, especially in the inscriptions and sculptures; probably few places in England can boast of so many interesting antiquities remaining in the neighbourhood where they were discovered. (8)

He was well aware, then, not only of the intrinsic merit of the Caerleon antiquities, but also of the value to scholars elsewhere of their publication; his book was designed to appeal not only to the curious and lovers of the picturesque but also to more serious antiquarians throughout the country. Its reception by reviewers was encouraging. A writer in the Archaeological Journal praised it highly for the ‘most praiseworthy care and fidelity’ of its drawings (9), a quality conspicuous in all of Lee’s later published works.

Lee concluded the introduction to his drawings with the words,

Sufficient has been shown that Caerleon is a place of unusual interest to the antiquarian: much however remains to be done by those who have leisure to devote to the subject… (10)

Exactly what remained to be done he did not specify. There is, for example, no mention of the desirability of a local museum to preserve the antiquities that had come to light. It seems likely, however, that if he had not already arrived at the conception of a museum and a society to bring it into being, the idea was not long in occurring to him. Two further developments may have hastened his decision: the occurrence of two sets of excavations at Caerleon, and the foundation of the Cambrian Archaeological Association.

A number of excavations aimed deliberately at exposing Roman remains at Caerleon had been made in recent years by Sir Digby Mackworth, the local squire. In 1843 a ‘considerable excavation’ had taken place on a site near the amphitheatre (the Kennel Field), where a small bathhouse was uncovered, though the finds proved disappointing. A well in the same field yielded ‘many fragments of Roman pottery’ (11). Within the walls Sir Digby found a ‘pavement of large stones’ at a depth of five feet in the garden of The Priory, associated with several layers of ash, and two hypocausts were also discovered in the same locality (12).

These excavations, however, were overshadowed in importance by two excavations of 1847. The first was the result of the building of a railway line (never completed) along the Usk valley, about half a mile north-east of the Roman fortress. The first discovery made during the construction of a cutting was of a stone coffin in the summer. Two more were unearthed nearby, together with several glass bottles, one of which contained cremated bones. At Lee’s suggestion an article describing these discoveries was contributed by the railway’s engineer, Francis Fox, to Archaeologia Cambrensis in September. The finds were intended to be removed to Brunel’s own museum, to the disappointment of Lee, who had hoped that they would be permitted to remain in Caerleon (15).

The second, larger scale excavation took place near the Castle Mound, just outside the south-east wall of the fortress, on a site owned by John Jenkins, Jnr., one of the leading citizens of the town. Exactly when the dig began is not known. Lee’s first published account of 1850 is vague (‘the last two or three years’), but a later source specifically links the origins of the Association to Jenkins’s excavation (14). Lee apparently superintended the dig, making plans and drawings of many of the objects found. The remains uncovered were of a large bathhouse, which had undergone at least one period of rebuilding. Archaeological work on the site continued for several years, and many notable finds came to light (15).

These excavations without doubt contributed to the movement to found an archaeological society in Caerleon; it is significant that one of the subsidiary aims of the Society was the organisation of ‘occasional excavations’. Equally important, however, were the examples set by the archaeological societies which had recently been established. The British Archaeological Association was founded in 1846 and nearer to home the Cambrian Archaeological Association in January 1847. Archaeologia Cambrensis, the Cambrians’ journal, gave Lee’s Delineations a favourable review in 1846, and the CAA included him as one of their members by April 1847. Another of the leading members of the Caerleon society, Thomas Wakeman, was one of those who originally ‘approved’ of the intention to establish the CAA in 1846; he later became the Local Secretary for Monmouthshire and served on the CAA’s Committee in 1847. The Caerleon society’s inaugural meeting was reported fully in Archaeologia Cambrensis (16). Lee and his colleagues were therefore well aware of the efforts being made, in Wales and in the rest of Britain, to create voluntary organisations in order to further archaeological work and research.

Whatever the relative importance of the motives of Lee and his friends — direct evidence is wholly lacking – an inaugural meeting of a new archaeological society was held at Lee’s house in Caerleon on 28th October 1947, under the chairmanship of Sir Digby Mackworth (17).

Sir Digby, 4th Baronet (1789-1852), was a descendant of Sir Humphrey Mackworth, the politician and mining entrepreneur. His early career was military, and he served with distinction in the Peninsular War and at Waterloo. Later he used his talents at home, to suppress riots in the Forest of Dean in 1830 and at Bristol in 1831. Succeeding to the title on the death of his father in 1838 he became Sheriff of Monmouthshire in 1843, and lived from 1820 until his death at Glen Usk, a few miles from Caerleon, a staunch pillar of the Church (he had founded the National Club in 1845 to unite the Anglican Church against Papism), the Conservative Party (he twice stood unsuccessfully as a candidate for Parliament) and local society (18). His support for the new Association was to be crucial in its early days.

It was resolved that the name of the new society should be the ‘Caerleon Antiquarian Association’, and that its objects should be ‘first, to form a museum of the antiquities found at Caerleon and in the neighbouring districts; and secondly, the furtherance of any antiquarian pursuit, whether by excavation or otherwise.’ Members were to comprise donors, to the amount of £2, gentlemen (5s annually), ladies (2s. 6d.) and those elected on account of valuable gifts to the museum. The officers would consist of a Patron, a President, a Secretary and six Committee members. An annual meeting would be held at Caerleon on the first Wednesday in July ‘for the election of officers, for the transaction of general business, and occasionally for excavations in the neighbourhood, and the delivery of original articles on antiquarian subjects.’ Officers were then elected to serve until the first annual meeting: Sir Digby Mackworth became President and Lee Secretary. It was announced that Sir Digby had offered a 99-year lease, at ls per annum, of the lower room of the Town Hall, and the upper room, if necessary. This offer was eagerly accepted. Owners of antiquities from Caerleon or its neighbourhood were requested to deposit them in the museum, where they would remain the property of the owner; in return donors would be entitled to free admission to the museum, which would otherwise be charged at a rate of 6d. per person. Edmund Jones of Bullmoor and Francis Fox, who had already donated objects, were elected as the first honorary members. Donations and subscriptions would be paid to the Secretary and the first annual subscriptions would become due on the first day of January 1848. Proceedings of the meeting would be printed, with an account of all donations and subscriptions, and copies sent to each member.

The aims and structure of the society adopted at this inaugural meeting were to remain the same throughout the nineteenth century and beyond. Significantly, and unlike the practice of other antiquarian societies, one aim was singled out above all others, the creation of a local museum (18A). Establishing and maintaining a museum of local antiquities and geological and botanical specimens was a regular part of the activities of many contemporary antiquarian and literary and philosophical societies, and some museums, like that of the Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, had attained considerable size and importance, but no other society had hitherto been formed with the principal purpose of founding a museum. Lee and his colleagues saw clearly that their first duty lay in preserving the numerous important Roman finds discovered in and around Caerleon, and that the only way of doing so successfully was to establish a local museum, properly administered by a voluntary organisation, which alone at the time possessed the continuity and means to maintain and extend it. The only alternative to a museum belonging to a society was one administered municipally. The Museums Act of 1845 had enabled councils to levy a halfpenny rate for the establishment of ‘museums of art and science’ and to make an admission charge. The Corporation of Canterbury took advantage of the Act to purchase the museum and library of the Philosophical and Literary Institution on behalf of the city. Such a solution was not available, however, to Caerleon, since the Act applied only to boroughs with a population of at least 10,000 inhabitants.

Private owners of antiquities could not be required to deposit them in the proposed museum, they could only be persuaded to do so. Hence the importance of enrolling them as members of the society and rewarding them for their generosity by the grant of free admission and honorary status. All donations were to remain the property of their donors; the society itself would simply house them and ensure their preservation.

Sir Digby Mackworth, who had through his sponsorship of excavations taken an active interest in Caerleon’s antiquities, solved one of the main obstacles facing the Association in its object of founding a museum, by his offer of the lease of part of the Town (or Market) Hall, an old building which stood in the centre of the town. Little is known of the building, except that, according to Coxe, it was supported by four Roman columns, which were later incorporated in the museum (19). It was therefore not anticipated at the outset that the Society would incur much expense other than in adapting and fitting out the Market Hall. Subscriptions were accordingly set at a relatively low level in comparison with those of similar societies (20). The costs of maintenance would be offset, at least in part, by an admission charge.

If the primary object of the society was clear enough, the secondary aims were much less so. The resolution passed at the inaugural meeting did not specify in detail what ‘any antiquarian pursuit’ might include, except for excavations. ‘Occasional excavations’ would be arranged to coincide with the annual meeting in July, at which the ‘delivery of original articles on antiquarian subjects would also take place. One obvious activity of antiquarian societies, the publication of a journal or monographs, received no mention at all.

Lee had succeeded in attracting as supporters of the new society some of the leading figures of local Caerleon society: not only Sir Digby Mackworth, but also John Jenkins, a well-known landowner and magistrate, and the vicar of the town, Rev. Daniel Jones, both of whom agreed to serve on the Committee. It was also agreed to ask the Bishop of Llandaff whether he would be willing to become Patron of the Association. With such a strong and influential body of opinion behind him Lee could feel confident that the society would survive to accomplish its objects.

The Monmouthshire Merlin, reporting the inaugural meeting, wished it well:

We trust that the society and its museum may go on and prosper; and that the inhabitants of the old city, which has too long slumbered, may be stimulated to improvement by the evidences of its ancient splendour.

2 The Museum to 1888

The first meeting of the newly formed Committee was held on 18th November (21). It soon became apparent that the plan adopted for the museum at the inaugural meeting could not proceed. Owners of properties near the Town Hall did not wish the building to be re-used, but preferred it to be demolished and would be willing to subscribe £80 for the ground on which it stood, provided it was not used again for building (22). Not only was the building, it was claimed, an ‘unsightly mess’ of no great antiquity and little architectural interest (with the exception of the Roman columns), but it was also an annoying obstruction to traffic. Sir Digby acknowledged the force of the townspeople’s objections and agreed to grant a lease to the society on a plot of land in another part of the town, on the same terms as his previous offer. He also offered to donate the whole of the £80, along with the value of the materials of the demolished building towards the construction of the new museum. The Committee readily agreed to the new proposals, even though it was likely that extra funds would be needed to complete the building. Some of the money necessary would come from an increase in the number of subscriptions: already ‘a considerable number of ladies and gentlemen of taste [have evinced] a disposition warmly to co-operate in the undertaking’, and subscriptions were ‘rapidly progressing’.

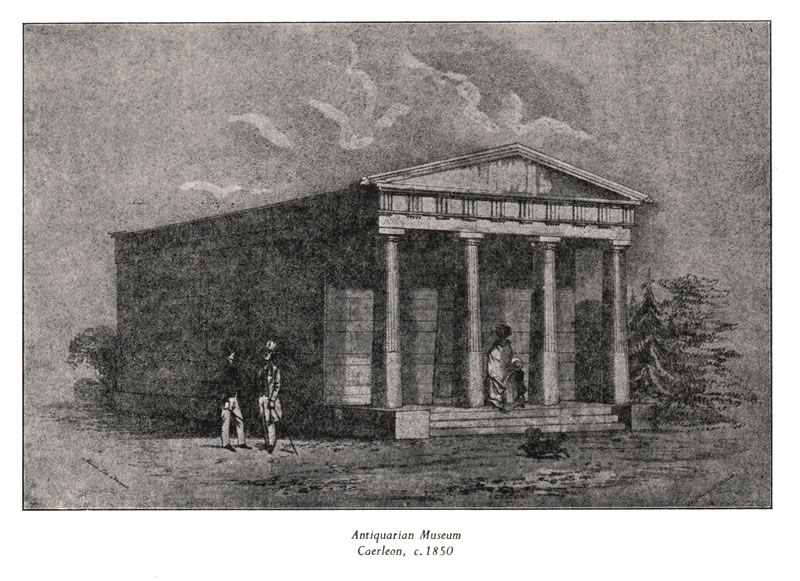

The Committee soon decided on the kind of building they needed (25). It would be a simple classical rectangular building with a prostyle porch in the Doric order, 20 feet by 40 feet inside and 16 feet high. The interior would be lit, as in some classical Greek temples, by a roof light. The man chosen to carry out the design was Henry Francis Lockwood, a Hull architect and old acquaintance of Lee’s, who later became architect to Sir Titus Salt, before moving to London in 1874 (24). He was willing to provide plans free of charge. On 7 March 1848 the plans and drawings were approved, and Mr. Benjamin James, builder, of Newport, was employed to prepare specifications and estimates. He agreed to execute Lockwood’s plans, except that the columns fronting the building were to be of brick and cement instead of stone, for £477 (25). Work would proceed until the roof was in place, by which time it was understood the sum of £174 10s 0d would have been spent. In June James was asked to start, and the ceremony of laying the foundation stone was held on 25 June. Speeches were made by Sir Digby Mackworth and William Addams Williams of Llangibby Castle, and the stone was laid by Miss Mackworth (26).

The Committee soon decided on the kind of building they needed (25). It would be a simple classical rectangular building with a prostyle porch in the Doric order, 20 feet by 40 feet inside and 16 feet high. The interior would be lit, as in some classical Greek temples, by a roof light. The man chosen to carry out the design was Henry Francis Lockwood, a Hull architect and old acquaintance of Lee’s, who later became architect to Sir Titus Salt, before moving to London in 1874 (24). He was willing to provide plans free of charge. On 7 March 1848 the plans and drawings were approved, and Mr. Benjamin James, builder, of Newport, was employed to prepare specifications and estimates. He agreed to execute Lockwood’s plans, except that the columns fronting the building were to be of brick and cement instead of stone, for £477 (25). Work would proceed until the roof was in place, by which time it was understood the sum of £174 10s 0d would have been spent. In June James was asked to start, and the ceremony of laying the foundation stone was held on 25 June. Speeches were made by Sir Digby Mackworth and William Addams Williams of Llangibby Castle, and the stone was laid by Miss Mackworth (26).

After only eight months, then, the Association had made extraordinary swift progress by the time of its first annual meeting, held in the Free School, Caerleon on Wednesday 5 July 1848 (27). Sir Digby Mackworth, in his introductory remarks, congratulated the society on its establishment and considerable achievement to date:

… not only have many of the neighbouring inhabitants freely come forward with their assistance, but within a few yards of us, we may see a building rapidly rising, which will decidedly be an ornament to the town, and, it is hoped, will be the place of deposit for all the antiquities found in this neighbourhood.

He recalled the origins and foundation of the society and reported on progress in the building of the museum. Requests to owners of antiquities in the area to deposit them with the society had met with success. Thanks to Francis Fox and others connected with the new railway, the finds made in the cutting near Caerleon had been secured, and two Roman inscriptions, removed from Caerleon 200 years before, had been recovered through the generosity of Charles Lewis of St Pierre (28). Financial donations, including the purchase money of the Town Hall and the value of the materials, amounted to £217 5s 6d; annual subscriptions totalled £14 15s. Expenditure, mainly on the production and distribution of circulars and engravings of the building, amounted to £7 7s 2d. A total of £252 was still required, therefore, if the museum was to be completed according to the original plans (29). ‘Though these sums appear large,’ Sir Digby concluded, ‘we do not despair; and we can only hope, that the interest which has already been excited will increase, and that the county will come forward to help the society to complete so handsome a building.’

Four papers were then read at the meeting, by Rev. Daniel Jones on ‘Traces of past generations in and around Caerleon’, Francis Fox on his discoveries during the construction of the railway, Thomas Wakeman on the history of Caerleon and J.M. Traherne on Peterstone Church. Traherne (1788-1860), of Coedriglan near Cardiff, was the outstanding antiquary of Glamorgan at the time. Wakeman, of The Graig, Monmouth, was by now the Local Secretary for Monmouthshire of the Cambrian Archaeological Association. Although not officer, it is likely that he was an early member of the society; later he was to become one of its leaders. Next, the officers of the Association were re-elected, with the addition to the Committee of two further men, Sir Charles Salusbury and Francis Fox. Then the whole party adjourned to Pilbach, a farm to the west of Caerleon belonging to John James, where an excavated Roman mosaic pavement was viewed (30). It was decided that a large part of the mosaic should be transferred to a board for eventual permanent preservation in the museum.

The building of the museum continued. By early 1849 the roof was in place. The columns from the old Town Hall, it was decided, should be incorporated, to support the floor of the museum instead of the cross wall provided in the contract. Progress in raising funds, however, was not so successful, and an advertisement was placed in local newspapers in March 1849 appealing for further donations. Contributions to date totalled about £260, leaving £200 yet to be found. The advertisement (31) detailed each of the 128 individual donations already made: most donors lived in Monmouthshire, but others came from London, Cheltenham and Swansea. The value of subscriptions had increased to £17 16s 0d, representing an increase of only about 12 – 20 extra members since the previous summer.

A few weeks later the Literary Gazette repeated the plea, in more ornate language, appealing both to the public spirit and to the self-esteem of the landed gentry who formed the obvious target of appeals:

Here is a sure and cheap speculation for lasting honour, to any rich gentleman who would like a niche in the temple of Fame… Let him abstract a hunter from his stud, or a dozen hounds from his pack, or give a dinner or two less yearly to the ‘country men’, and endow the maiden of Caerleon Museum. (52)

The effect of these appeals was, however, less than had been hoped. At the second annual meeting, on 5 July 1849 (33), the Secretary had to report that in spite of a few more donations £180 was still required to complete the museum. He confessed that ‘…the state of the funds, it will be seen, requires help, and, in some respects, it is not encouraging’. A statement of the society’s cash account since its foundation showed that a total of £512 0s 6d had been spent, £256 of which had been paid to the contractor for work on the museum, £6 4s 4d on the cost of excavations, and £20 12s 4d on advertising, printing, stationery and postage, leaving a balance in hand of only £30 9s 9d. Another appeal was therefore made for financial contributions: ‘… the committee would urge on the members the expediency of inducing their friends, and especially such of the country gentlemen as have not already come forward, to aid in supporting so desirable and interesting an institution’. Now, however, other help was at hand:

The effect of these appeals was, however, less than had been hoped. At the second annual meeting, on 5 July 1849 (33), the Secretary had to report that in spite of a few more donations £180 was still required to complete the museum. He confessed that ‘…the state of the funds, it will be seen, requires help, and, in some respects, it is not encouraging’. A statement of the society’s cash account since its foundation showed that a total of £512 0s 6d had been spent, £256 of which had been paid to the contractor for work on the museum, £6 4s 4d on the cost of excavations, and £20 12s 4d on advertising, printing, stationery and postage, leaving a balance in hand of only £30 9s 9d. Another appeal was therefore made for financial contributions: ‘… the committee would urge on the members the expediency of inducing their friends, and especially such of the country gentlemen as have not already come forward, to aid in supporting so desirable and interesting an institution’. Now, however, other help was at hand:

Besides the donations which have been announced, the ladies of the county have taken the matter into their hands, and in conjunction with the committee, have determined on a bazaar, to be held in aid of the museum funds …’

The ‘ladies’, among them Lady Mackworth, Lady Morgan, Mrs Hanbury Leigh, Miss Salusbury and Miss Elizabeth Salusbury, had hit upon a sure method of persuading the local upper classes to part with their money: the grand county social event. Lieut.-Col. Barlow was prevailed upon to allow the band of the 14th Regiment to attend, and the date was set for 25 July.

Having dealt with finance, the Secretary moved on to a restatement of the objects of the Association. The principal aim was still to establish the museum. It was emphasised that the museum was intended to house only antiquities, especially local antiquities, however desirable it might seem to have a general philosophical museum in the neighbourhood. This policy was in line with the society’s determination throughout the period to concentrate its activities on archaeology and local history, and not to imitate other Welsh societies with broader interests and thereby dissipate its energies. The secondary aims of the society were specified in rather more detail than previously:

… to disseminate and keep alive a taste for [antiquarian] pursuits, by as frequent excavations amongst ancient foundations, as the funds will admit of; by keeping a watchful eye on whatever is found of interest, and, if possible, securing it for the museum; and also, if of general interest, by taking means to have it published in one of the archaeological journals, or some eligible work.

Excavation had increased in importance in the eyes of the Committee since the inaugural meeting, possibly following the success of the excavations at Pilbach and the Castle Mound. It was pointed out that although for obvious reasons little money had hitherto been spared to finance digs, it was hoped that ‘several excavations’ would be undertaken during the following year. The Pilbach mosaic had been lifted for transference to the completed museum; a second mosaic, of three colours and finer workmanship, had been discovered close to the first. An attempt would be made to lift it, too (34). Another discovery during the year had been that of two ivory plaques, found by John Jenkins while digging a drain near his home (35). On exposure to air and water the surface of the ivories began to flake away, and the plaques would have disintegrated had not Lee immediately treated them with a solution of isinglass in spirits of wine, a technique applied to ivory carvings recently recovered at Nimrud by A.H. Layard. So many finds were constantly coming to light that ‘the wonder would probably be, not that Caerleon and the neighbourhood is now building a museum, but that so long a time has elapsed before a museum has been built.’

Excavation had increased in importance in the eyes of the Committee since the inaugural meeting, possibly following the success of the excavations at Pilbach and the Castle Mound. It was pointed out that although for obvious reasons little money had hitherto been spared to finance digs, it was hoped that ‘several excavations’ would be undertaken during the following year. The Pilbach mosaic had been lifted for transference to the completed museum; a second mosaic, of three colours and finer workmanship, had been discovered close to the first. An attempt would be made to lift it, too (34). Another discovery during the year had been that of two ivory plaques, found by John Jenkins while digging a drain near his home (35). On exposure to air and water the surface of the ivories began to flake away, and the plaques would have disintegrated had not Lee immediately treated them with a solution of isinglass in spirits of wine, a technique applied to ivory carvings recently recovered at Nimrud by A.H. Layard. So many finds were constantly coming to light that ‘the wonder would probably be, not that Caerleon and the neighbourhood is now building a museum, but that so long a time has elapsed before a museum has been built.’

After the reading of papers by Sir Digby Mackworth, Lee, Rev. Daniel Jones and Rev. C.W. King, the members visited the excavation on the site of the Castle Baths (36) and then assembled in the Roman amphitheatre for ‘an excellent and substantial luncheon.’

After the reading of papers by Sir Digby Mackworth, Lee, Rev. Daniel Jones and Rev. C.W. King, the members visited the excavation on the site of the Castle Baths (36) and then assembled in the Roman amphitheatre for ‘an excellent and substantial luncheon.’

The bazaar, held at The Priory in brilliant weather, proved a considerable success. ‘There have been few public occasions’, reported the Merlin (37), ‘in this county that have called together a more numerous, respectable, and indeed, distinguished assemblage than the present. We should suppose that about 500 persons visited the Priory, and amongst them were families of the highest station …’ (58). Visitors could buy goods at numerous stalls, Mr Morris, lithographic printer, sold prints of Roman antiquities, the band played, the bells of Caerleon church pealed, and the day ended with a dance. It was announced that altogether £195 had been raised in aid of the museum (39). The bazaar had ‘succeeded far beyond the most sanguine expectations of any of its promoters’ (40), and enabled the building of the museum to continue. The members of the Cambrian Archaeological Association, in Cardiff for their annual meeting, had a chance to see the progress of the museum on their visit to Caerleon on 29 August.

January 1850 saw the publication of Lee’s account of the excavation of the Castle Baths, with two plans and 18 plates from his own drawings. Any profits arising from its sale he intended to devote to the museum fund, but despite favourable reviews, both locally and nationally, it appears that sales were not large enough to produce a surplus (41).

Still £100 remained to be raised. Meanwhile problems in the construction of the museum building had come to light (42). Several of the roof lights had been broken. The joiner employed by Messrs Cordes and Co. reported that much work, including that on laths, roof lead, gutters and skylight, had not been completed according to specification. The Committee engaged an architect, Mr Lloyd of Bristol, to supervise the rest of the building. He confirmed the deficiencies in the construction. After some complex negotiations Mr James finally agreed to re-execute the work already done in accordance with the specifications and contract under Mr Lloyd’s direction (43). At last, on 13 June 1850, James gave his final certificate to the Committee. Since the Association had not yet raised sufficient funds, Lee had to negotiate credit terms with its bankers so that James could be paid. In all James was paid £537 19s 0d, while £15 15s 2d was paid to the architect. By the time of the annual meeting, on 17 July 1850, £60 was still owed to the bank (44).

Still £100 remained to be raised. Meanwhile problems in the construction of the museum building had come to light (42). Several of the roof lights had been broken. The joiner employed by Messrs Cordes and Co. reported that much work, including that on laths, roof lead, gutters and skylight, had not been completed according to specification. The Committee engaged an architect, Mr Lloyd of Bristol, to supervise the rest of the building. He confirmed the deficiencies in the construction. After some complex negotiations Mr James finally agreed to re-execute the work already done in accordance with the specifications and contract under Mr Lloyd’s direction (43). At last, on 13 June 1850, James gave his final certificate to the Committee. Since the Association had not yet raised sufficient funds, Lee had to negotiate credit terms with its bankers so that James could be paid. In all James was paid £537 19s 0d, while £15 15s 2d was paid to the architect. By the time of the annual meeting, on 17 July 1850, £60 was still owed to the bank (44).

Although the building was now complete, it was not possible to exhibit anything but the larger monuments, in the absence of cases, for which the Committee had no funds available. It was necessary to make a further appeal to the generosity of the members and the public. According to the Secretary, ‘If only the fitting-up of the museum could be completed, and the debt paid off, the yearly subscriptions will be amply sufficient, for all the wants of the society.’ In 1850 subscriptions had raised over £40. The appeal was duly published in the Monmouthshire Merlin on 31 August. A total of £100 was needed, both to pay off the debt and to complete the interior of the museum. Members and their friends were welcome to visit the museum and the few objects of interest displayed, at no charge. The key could be obtained from the newly-appointed curator, Thomas Powell, at the Post Office.

An additional incentive to furnish the museum as quickly as possible was that the Archaeological Institute, due to meet in Bristol in 1851, had proposed a visit to Caerleon. It was agreed to hold the annual meeting of the Association on the same day, 4 August. By this time nearly all the objects of interest were displayed, even if not in the most satisfactory way, as Lee admitted. The Archaeological Institute members were highly appreciative: ‘… through the praiseworthy and indefatigable exertions of Mr Lee, a large assemblage of local antiquities has already been arranged, with the happiest effect’ (45). What the Committee had done was to spend what funds had been raised from donations, not to pay off the debt owed to the bank, but on cases and other equipment to furnish the museum. As a result £60 was still owed to the bank. The Committee trusted that the members would approve of the measures it had taken, in view of the Archaeological Institute’s visit.

A newspaper account of the visit gives a brief, but vague indication of the layout of objects in the museum (46). The upper, or main floor was devoted to the display of a tessellated pavement, several tombstones found by Edmund Jones at Bullmore and various other ‘ponderous’ antiquities, together with smaller objects in glass cases. The lower chamber was given over to the stone coffins discovered by Fox and a ‘variety of other matters more suitable for inspection there’. No detailed description of the contents of the museum is available until 1862.

The completion of the museum represented the coming to fruition of the first of the Association’s aims, after five years of determined effort. At last Lee and his associates had removed the stigma attaching to the people of Caerleon, that they had disgracefully neglected their ancient remains. As long ago as 1796 David Williams, in his History of Monmouthshire, had protested about the removal of Caerleon’s antiquities and had advocated the establishment of a local museum devoted entirely to their preservation (47). Now that museum had been brought into being, despite some setbacks, one of which, the faulty workmanship of its construction, would cost the society dear in the future.

After such an achievement the Committee could perhaps be forgiven for resting on its laurels. There were few developments of any significance during the following year. ‘No objects of any great interest have been discovered’, reported Lee to the annual meeting on Thursday 1 July 1852 (48), although some additions were made to the museum. At Easter more than 500 people had visited it. Financial problems, however, still remained. There was still a debt to the bank of £60. For the first time Lee was forced to admit that the levels of subscription had been set too low; total income, from 58 subscribing members and 21 life members, had been ‘considerably under £20.’

Only three months after the annual meeting the society lost one of its most valuable members, with the death on 22 September of Sir Digby Mackworth. Although he contributed little to scholarship — his only paper to the society, delivered in 1849, attempted to prove that St Paul had preached in Britain — there is little doubt that without his financial generosity the museum would not have been built and the society might not have been formed.

Sir Digby’s successor as President was Octavius Morgan (1803-1888) (48A). He was the fourth son of Sir Charles Morgan, 2nd Baronet, of Tredegar Park, and the brother of the first Baron Tredegar. The Morgans had been since the middle ages and still remained one of the wealthiest and most powerful families in Monmouthshire. A strong Tory and anti-papist, Octavius Morgan represented the county in Parliament from 1840 to 1874 (49). He had participated as a juryman in the trial of the Chartist leader John Frost in 1840. A knowledgeable and well-respected antiquary, he had been elected a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries in 1850. In Wales he was a leading member of the Cambrian Archaeological Association and of the Welsh Manuscripts Society, and, although apparently not a founder member, had served on the Committee of the Caerleon society since 1849. No one, with the sole exception of J.E. Lee, did more to determine the direction the society was to take in the next 30 years, and none contributed more to the number and quality of its publications.

Under Morgan’s guidance the finances of the society began to look healthier. By the summer of 1853 the debt owed had been reduced from £60 to £45; the following year a lottery was organised at the annual meeting to raise funds, and it was proposed to sell one of the society’s publications to the public to pay off the debt entirely. By 1855 this had been achieved and Lee was able to report that a balance of £5 10s 10d existed in the cash account. Partly at the President’s expense necessary repairs to the museum, including the replacement of the roof and water pipes and the building of a drain to protect the lower room from dampness, were completed, and the exhibits were reorganised and properly labelled (50).

The achievement of financial stability enabled the Association to proceed with a plan to publish an illustrated catalogue of the museum (51). This volume, almost entirely the work of Lee, was published in London in 1862 and gives the earliest comprehensive picture of the contents of the museum (52). All the exhibits were illustrated, by Lee himself, with the exception of those not found in Caerleon or its neighbourhood and the coin collection. By far the majority are Roman. They include 31 inscriptions, 14 sculptured stones, 65 fragments of samian and coarse pottery, two mosaics, 21 glass objects, two ivory carvings and numerous objects of bone, bronze and iron. In addition the museum contained a small number of prehistoric finds, mainly from the excavation of Penhow barrow, two fragments from early Christian crosses and miscellaneous medieval antiquities. A high proportion of the Roman finds (30%) were discovered during the excavation of the Castle Baths and were presented to the museum by the owner of the site, John Jenkins Jnr. Many others came from the Caerwent excavations of 1855 and other smaller excavations in and around Caerleon and Usk. Others, however, were chance finds, discovered in fields, gardens and house foundations and donated by a great variety of people (almost fifty in all); it was these objects that, but for the existence of the museum, might most easily have been lost.

The achievement of financial stability enabled the Association to proceed with a plan to publish an illustrated catalogue of the museum (51). This volume, almost entirely the work of Lee, was published in London in 1862 and gives the earliest comprehensive picture of the contents of the museum (52). All the exhibits were illustrated, by Lee himself, with the exception of those not found in Caerleon or its neighbourhood and the coin collection. By far the majority are Roman. They include 31 inscriptions, 14 sculptured stones, 65 fragments of samian and coarse pottery, two mosaics, 21 glass objects, two ivory carvings and numerous objects of bone, bronze and iron. In addition the museum contained a small number of prehistoric finds, mainly from the excavation of Penhow barrow, two fragments from early Christian crosses and miscellaneous medieval antiquities. A high proportion of the Roman finds (30%) were discovered during the excavation of the Castle Baths and were presented to the museum by the owner of the site, John Jenkins Jnr. Many others came from the Caerwent excavations of 1855 and other smaller excavations in and around Caerleon and Usk. Others, however, were chance finds, discovered in fields, gardens and house foundations and donated by a great variety of people (almost fifty in all); it was these objects that, but for the existence of the museum, might most easily have been lost.

In addition to a catalogue of the museum’s contents, Isca also included versions of the papers by Lee, Morgan and Wakeman on the Castle Baths Caerwent excavations and on the early history of Caerleon. At 148 pages, with 52 plates, it was the most substantial volume the Association ever produced. One of its aims, to draw the attention of archaeologists throughout the country to the richness of Caerleon’s Roman collections, was almost immediately fulfilled. Highly favourable reviews began to appear in the most influential journals, the Gentleman’s Magazine, Archaeological Journal and Journal of the British Archaeological Association (53). One reviewer, recommending its purchase for ‘the small price of fifteen shillings’, commented, ‘Few places have been so fortunate as to obtain means for the erection of an appropriate building for the reception of the antiquities discovered at various times in the locality’; another highlighted the collection of Roman inscriptions, ‘unequalled in interest by any in the southern parts of the kingdom’, and criticised other museums, such as those at York, Shrewsbury, Bath and Colchester, for reducing the value of their collections by failing to produce catalogues of equal quality. Copies were sent by Morgan to museums both in Britain and abroad, and elicited universal approval (54). It would be no exaggeration to say that after 1862 no student of Romano-British archaeology could afford to ignore the importance of Caerleon Museum. Interest was still strong in 1868, when Lee issued a supplement, to include new accessions and to add new information on items already described.

In the following two decades a number of important finds were deposited in the museum, among them the ‘maze’ mosaic from Caerleon churchyard (1866), discoveries made by A.D. Berrington in his excavations at Usk (from 1878), the Roman stone from Goldcliff (1879-80) and the rood figure from Kemeys Inferior Church (1886); many smaller donations, notably of coins, were also made. Nevertheless, the fact that the President found it necessary to appeal so frequently for donations, and that the Secretary had to admit in many of his annual reports that little or nothing had been added to the museum since the last meeting, suggests that it could no longer attract the volume of material that had flooded into it in its early years (55). But the main problem with the museum was its physical condition. The defects of its construction now made themselves felt, as the Association was obliged to devote more and more of its scarce funds to repairs. The roof was giving particular trouble. Only eleven years after it had been re-slated further repairs were necessary; two years later yet more were required, and in 1873 still more. Even so the skylight persisted in leaking (56). All this repair work represented a considerable drain on the society’s finances, which might otherwise have been spent in more constructive ways. Nevertheless, it was possible to make improvements: a subscription fund was established to help erect railings around the museum, complete by 1864, and in 1881 Morgan carried out a rearrangement of the exhibits at his own expense; the walls were painted, new shelving was erected and new cases added; a new stove was also installed (57). By the 1880s the museum was being visited by increasing numbers of people. It was opened on public holidays, such as Easter Monday, Bank Holiday and Whit Monday, so that the ‘public taste for antiquities’ could be educated; the reward was an increase in the amount of donations placed in the museum box (58). Clearly the fame of the museum was spreading, both locally and further afield. The Committee was aware, too, that public knowledge of and regard for the museum could work to the society’s own advantage: ‘This [opening of the museum as often as was possible] is a mode of educating people to appreciate antiquities which will do much to preserve them when they are found’ (59). The Association, it might be concluded, was now in a good position to cater for the striking expansion of interest in archaeology which occurred throughout Britain in the final years of the nineteenth century.

3 Membership and meetings to 1888

Consideration of the membership of the Association is handicapped by the paucity of membership lists throughout the nineteenth century. The earliest surviving complete list is for 1863; the others are dated 1882, 1892 and 1894. The only other evidence is provided by occasional aggregates of subscription income and by estimates of those present at the annual meetings, which appear in a few of the newspaper reports.

It is clear that the originators of the society comprised a small group of people formed around J.E. Lee, but membership must have increased rapidly, to judge from the generous financial support afforded the Association by many sources towards the establishment of the museum. By the time of the first annual meeting in July 1848 £217 5s 6d had been donated and £14 15s had been collected in subscriptions. It is not easy to translate the latter figure into a total number of members, because of the differential subscription rates obtaining. Members consisted of ‘donors’ who contributed £2 or above, ‘ladies’ who subscribed 2s 6d annually, and ‘gentlemen’ who subscribed 5s. However, assuming that all ‘donations’ are included in the larger figure, and that there were at least as many men as women, it may be surmised that total membership amounted to between 59 and 78. By March 1849 the amount raised by subscription had increased by £3 10s 0d. By July 1850 the total amount collected since the foundation of the society stood at £40 7s 6d, a sum which clearly reflects a sudden upsurge in recruitment. Further gains appear to have been made in the succeeding years, until by 1855 a total of £129 13s 6d had been collected. An estimate of the number of people attending an annual meeting of 1857 gives a figure of ‘not less than 200 ladies and gentlemen’, but it must be remembered that ‘visitors’ as well as subscribing members could participate. The number of attenders tended to fluctuate widely, depending on the weather, the accessibility of the venue or the coincidence of rival attractions: the 1856 meeting could muster only 100 people, the 1858 meeting only 50, but by 1863 the number had risen to 150.

The list for 1863 (60) gives a total of 131 members, with in addition 17 people described as ‘life members not regularly subscribing’ (61). All but 32 of the total lived in Monmouthshire; surprisingly, considering the origins and early history of the Association, comparatively few (15) came from Caerleon and its immediate neighbourhood. A further 25 lived in or around Newport, 14 in Monmouth, 10 in Usk and 8 in Chepstow. Otherwise they were spread fairly evenly throughout rural Monmouthshire, but very sparsely in the coal valleys in the west of the county. That this was so is hardly surprising, since the society was heavily dominated by the clergy and landed and titled gentry, classes notable for the scarcity in the raw and rapidly industrialising townships of the valleys, which were, and remained, overwhelmingly working class in character. Of the total 40 were clergymen or their wives, and at least the same number were titled or possessed considerable estates. This preponderance of the leisured and highly privileged remained an abiding characteristic of the Association throughout the nineteenth century and well into the twentieth century.

Only 24 of the total of 131 members in 1863 were women, and of these as many as 14 may have owed their membership to the inclusion of their husbands or relatives, rather to any independent interest in local antiquities. However, as with the Cambrian Archaeological Association, such a low figure probably fails to reflect accurately the active participation of women in the social aspects of the society’s activities. Far more women attended the summer meetings than subscribed as members; at Pencoed in 1858, for example, half of the 50 who attended were female (62). We have seen how the success of the bazaar in raising funds for the museum in 1849 was attributable largely to the ‘ladies’.

Membership figures remained remarkably stable during the next two decades, despite repeated pleas for the recruitment of new members (65). In 1865 140 people were subscribers; by 1882 the number had fallen slightly to 150, 29 of whom were women. The social composition of the members had also changed little, except that the number of clergymen had decreased to 27. The lack of any substantial increase in membership implied that the society’s finances also failed to improve, since subscription fees remained at their original levels (except that married ladies were now expected to pay 5s).

In exchange for their subscription members were entitled to receive the society’s publications free of charge, and to attend the annual summer meeting. During the early years meetings were, naturally enough, held at Caerleon, in the Free School. In 1853 it was decided to vary the venue (perhaps the death of Sir Digby Mackworth had removed the necessity to meet at Caerleon) and the members assembled at Caldicot Castle, by permission of the tenant. Papers on the architecture and history of the castle by Octavius Morgan and Thomas Wakeman were read and then about 80 ladies and gentlemen sat down to luncheon in part of the castle yard (64). Next year the meeting reverted to Caerleon, but 1855 saw the Association congregating at Caerwent, to view the excavations within the Roman town, and in 1856 Usk was visited. The interests of the leaders of the society, especially Morgan and Wakeman, and of the membership as a whole had clearly widened from Caerleon to encompass the whole county. This tendency received recognition in 1857 when, at the instigation of the President, Octavius Morgan, the society decided to change its name to the Monmouthshire and Caerleon Antiquarian Association. The motive for the change was to enlist as members potentially interested inhabitants of the county who might be under the impression that the society’s province was confined to Caerleon: ‘it would lead to an increase of members and spread a greater interest through the county in antiquarian matters’ (65). As it happened, no significant increase in membership seems to have been forthcoming, but from 1857 the society truly regarded the county of Monmouthshire, rather than simply Caerleon, as its area of interest. Caerleon was retained in its name as a mark of its importance in the foundation of the society and the museum.

It would, however, be an exaggeration to say that the Association gave equal attention to all parts of the county. A distribution map of the venues of annual meetings between 1848 and 1926 (fig. 1) shows that sites in the rural south and east of the county were favoured, at the expense of the western, industrialised Valleys, a preference which reflects not merely the greater abundance of archaeological sites in the lowland regions but also the geographical spread and class character of the society’s members. Instead of venturing westwards (only three trips were made into Glamorgan) they were more inclined to cross the border into Gloucestershire and Herefordshire, where they could rely on the hospitality of their fellow landed gentry.

It would, however, be an exaggeration to say that the Association gave equal attention to all parts of the county. A distribution map of the venues of annual meetings between 1848 and 1926 (fig. 1) shows that sites in the rural south and east of the county were favoured, at the expense of the western, industrialised Valleys, a preference which reflects not merely the greater abundance of archaeological sites in the lowland regions but also the geographical spread and class character of the society’s members. Instead of venturing westwards (only three trips were made into Glamorgan) they were more inclined to cross the border into Gloucestershire and Herefordshire, where they could rely on the hospitality of their fellow landed gentry.

For most of the Association’s members the annual summer meeting was the most interesting and important aspect of its activities, and very often assumed the character of a leading event in the diaries of county society. The visit to Caldicot in August 1853 was typical of the best-attended occasions (66). It was a Thursday: meetings were invariably held during the week, when those unfortunate enough to depend for their living on a regular job were unable to attend. At twelve o’clock a large number of members and their friends arrived at the castle. Thomas Wakeman took the chair for the initial business meeting, conducted from a mound near the west entrance. The proceedings of the last meeting and the Committee’s report were read by the Secretary, the officers were elected (very little change in their composition took place from year to year), and then the Rev. E. Turberville Williams of Mount Balan read some remarks of Octavius Morgan, who was unavoidably absent, on the architecture of the castle. After some discussion of this paper, Wakeman read a piece on the early history of the castle. Next the party retired to another corner of the castle yard, where tables were spread for luncheon, thanks to the contributions of members and of families resident in the area: the offerings included a lamb roasted whole, donated by the vicar of Caldicot. Following the meal, the Rev. John Armstrong of Tideham was prevailed upon to escort members around the castle, pointing out as he did so the peculiarities of the architecture.

In 1867 the members descended in large numbers, despite the difficulty of access, on the village of Trellech. After visits to the local antiquities (‘Harold’s Stones’, the Norman motte and the church), they separated into two parties, one lunching in the school room, the other in the club-room of the Crown Inn. The afternoon brought rain, so the proceedings continued in the barn of the inn: ‘straw was strewn about the ground, and as the ladies entered heartily into the gypsy fashion of seating themselves, whilst the gentlemen stood around the president and secretary, the former being mounted on the granary wall, the effect was very picturesque.’ (67).

In 1867 the members descended in large numbers, despite the difficulty of access, on the village of Trellech. After visits to the local antiquities (‘Harold’s Stones’, the Norman motte and the church), they separated into two parties, one lunching in the school room, the other in the club-room of the Crown Inn. The afternoon brought rain, so the proceedings continued in the barn of the inn: ‘straw was strewn about the ground, and as the ladies entered heartily into the gypsy fashion of seating themselves, whilst the gentlemen stood around the president and secretary, the former being mounted on the granary wall, the effect was very picturesque.’ (67).

This mixture of sight-seeing, lectures and socialising proves so attractive that the formula remained virtually unchanged throughout the society’s history, even when most of its other activities had ceased.

4 Excavations to 1888

Excavations on a small scale in and around Caerleon preceded, as we have seen, the establishment of the Association, and they continued to form one of its major interests after the setting up of the museum. By far the most important of the excavations conducted under the auspices of the society were those on the site of the Castle Baths, Caerleon, between 1847 and 1851, and at Caerwent in 1855.

The origins of the Caerleon excavation have already been described (66). Some uncertainty surrounds the circumstances of the enterprise, particularly its funding and direction. J.E. Lee appears to have been responsible for the job of supervision; initial financial resources were probably provided by the owner of the property, John Jenkins. Later the society itself granted funds to the project: by 1849 it had spent a total of £6 4s 4d on the cost of ‘excavations, wood for trays, labour and sundry expenses’; doubtless, however, private funding continued, since the dig did not finish until at least 1851 and covered a considerable area of land: ‘none of our societies of antiquaries’, Lee proudly announced, ‘would have ventured on a work of such magnitude’. The excavations revealed a large complex of interconnected buildings, of at least two periods, which included, in the earlier period, an extensive hot and cold bath system, and in the later period, a large courtyard and basilica. Lee’s circumspect account of the discoveries (69) describes each room in turn and illustrates many of the more interesting finds, noting where appropriate comparative finds from other sites, but fights shy of attempting a detailed interpretation. Notably absent is any discussion of the date of the remains: stratified coins were not yet appreciated for the dating evidence they could provide (70), nor, of course, was Samian pottery, examples of which Lee illustrated for their intrinsic interest. Nonetheless, allowing for the fact that he lacked the tools of interpretation available to later excavators, Lee can be considered to have excavated and described the remains of the baths as intelligently and diligently as most of his contemporaries could have done in similar circumstances. It is worth noting that the excavation was complicated not only by the changes in use of the Roman buildings, but also by disturbance of the site, which was later occupied by the bailey of the medieval castle (71).

The origins of the Caerleon excavation have already been described (66). Some uncertainty surrounds the circumstances of the enterprise, particularly its funding and direction. J.E. Lee appears to have been responsible for the job of supervision; initial financial resources were probably provided by the owner of the property, John Jenkins. Later the society itself granted funds to the project: by 1849 it had spent a total of £6 4s 4d on the cost of ‘excavations, wood for trays, labour and sundry expenses’; doubtless, however, private funding continued, since the dig did not finish until at least 1851 and covered a considerable area of land: ‘none of our societies of antiquaries’, Lee proudly announced, ‘would have ventured on a work of such magnitude’. The excavations revealed a large complex of interconnected buildings, of at least two periods, which included, in the earlier period, an extensive hot and cold bath system, and in the later period, a large courtyard and basilica. Lee’s circumspect account of the discoveries (69) describes each room in turn and illustrates many of the more interesting finds, noting where appropriate comparative finds from other sites, but fights shy of attempting a detailed interpretation. Notably absent is any discussion of the date of the remains: stratified coins were not yet appreciated for the dating evidence they could provide (70), nor, of course, was Samian pottery, examples of which Lee illustrated for their intrinsic interest. Nonetheless, allowing for the fact that he lacked the tools of interpretation available to later excavators, Lee can be considered to have excavated and described the remains of the baths as intelligently and diligently as most of his contemporaries could have done in similar circumstances. It is worth noting that the excavation was complicated not only by the changes in use of the Roman buildings, but also by disturbance of the site, which was later occupied by the bailey of the medieval castle (71).

Finds from the excavation were safely preserved in the newly constructed museum. Lee was able to report with satisfaction that the altar found by John Jenkins early one day was deposited by him in the museum in the afternoon, ‘thus rendering it perfectly secure from further injury’ (72). News of the dig spread – one distinguished visitor during 1848 was Charles Roach Smith — but apparently not far enough, because John Jenkins, although eager to preserve the remains for inspection, found after several months that only three or four individuals had visited the site, and decided to destroy them, much to the distress of the members of the British Archaeological Association who visited the site during their Chepstow conference in 1854 and found it ‘being trenched for the purpose of laying down draining pipes’(73).

Some years elapsed before the next major excavation, and the first to be sponsored officially by the society, at Caerwent in 1855. It represented a bold extension of the Association’s interests outside the immediate area of Caerleon, and prefigured its change of name two years later, but had, apparently, been a ‘long-cherished wish’ of the leading members (74). It was especially dear to the heart of Octavius Morgan, who, on his return from a visit to Italy in 1828, remarked of Caerwent ‘this is the Monmouthshire Pompeii’, so convinced was he of the archaeological potential of the Roman town (75). Hitherto no planned excavations had taken place. The town walls were visible, together with their towers, but little had been recovered from the interior with the exception of a number of mosaics, the most recent of which was exposed in 1777. The modern village was small and enough of the interior of the Roman town lay undisturbed to encourage Morgan in the view that properly excavated excavations would yield worthwhile results.

The immediate stimulus to excavate, however, appears to have come not from the Caerleon society, but from the British Archaeological Association. The BAA visited Caerwent as part of its Chepstow meeting in August 1854. Passing through an orchard in the southeast corner of the Roman town, members saw so many signs of Roman buildings that the owner, Rev. Freke Lewis, was asked to grant permission to the Association to excavate. Having gained his assent, the Council of the BAA began to arrange for the dig and invited local antiquaries to participate. The plans were, however, halted abruptly by the disclosure of a scandal, the details of which remain unclear. According to the report of an extraordinary general meeting of the BAA, held on 6 December 1854, correspondence was read ‘respecting the Caerwent excavations, including communications from Dr Trevor Morris and Mr Wakeman, by which it appeared that the labours of that committee had been interrupted in consequence of certain letters written by the Rev. T. Hugo to the Rev. Freke Lewis and Mr Octavius Morgan, and the interest and honour of the Association thereby seriously affected’. A motion that Thomas Hugo should resign his position as Secretary of the BAA, having laid a false accusation against T.J. Pettigrew, the Treasurer, was passed. As a result the BAA withdrew from the Caerwent project, to avoid what was termed ‘the jealous opposition of certain local antiquaries’ (76), thus leaving the field open to the Caerleon society.

The immediate stimulus to excavate, however, appears to have come not from the Caerleon society, but from the British Archaeological Association. The BAA visited Caerwent as part of its Chepstow meeting in August 1854. Passing through an orchard in the southeast corner of the Roman town, members saw so many signs of Roman buildings that the owner, Rev. Freke Lewis, was asked to grant permission to the Association to excavate. Having gained his assent, the Council of the BAA began to arrange for the dig and invited local antiquaries to participate. The plans were, however, halted abruptly by the disclosure of a scandal, the details of which remain unclear. According to the report of an extraordinary general meeting of the BAA, held on 6 December 1854, correspondence was read ‘respecting the Caerwent excavations, including communications from Dr Trevor Morris and Mr Wakeman, by which it appeared that the labours of that committee had been interrupted in consequence of certain letters written by the Rev. T. Hugo to the Rev. Freke Lewis and Mr Octavius Morgan, and the interest and honour of the Association thereby seriously affected’. A motion that Thomas Hugo should resign his position as Secretary of the BAA, having laid a false accusation against T.J. Pettigrew, the Treasurer, was passed. As a result the BAA withdrew from the Caerwent project, to avoid what was termed ‘the jealous opposition of certain local antiquaries’ (76), thus leaving the field open to the Caerleon society.

The Caerleon Association was unable to meet the costs of a comparatively large-scale excavation such as Morgan intended from its own meagre funds, and it was therefore necessary to set up an excavation fund and invite subscriptions from sympathisers within and beyond the county. The response was generous, £45 14s being donated by August 1855. The next problem was who should direct the excavation. Neither Morgan nor Lee felt able to take on the burden of responsibility, and at first no suitably qualified archaeologist could be found. Finally, however, John Yonge Akerman, the Secretary of the Society of Antiquaries of London, offered to oversee and direct the work. It was a wise choice. Akerman was a keen numismatist, a prolific writer on archaeological themes, and, most important, a careful and experienced excavator. For several weeks during the summer of 1855 he gave his whole time to directing the workmen at Caerwent.

The site chosen lay in the south-east corner of the town, close to the Norman motte. It was here that the mosaic had been discovered in 1777. Two separate buildings were unearthed, the first apparently a house, the second a small but complete set of baths. Despite the discovery of numerous coins and Samian pottery in the foundations of the house, the excavator was unable to establish any chronology for the several rebuildings that had apparently taken place, or indeed to suggest a coherent plan. The bath-house proved easier to interpret. A complete plan was obtained, and it was possible to assign a function to each of its rooms by tracing the passage of heated air from the furnace through the hypocaust system, much of which survived fairly intact. A plan of the building was drawn by Alexander Bassett, a civil engineer from Cardiff, and a mahogany model was constructed, which was deposited in the museum at Caerleon; it was not possible to preserve the site. A fine mosaic floor, together with other finds from the excavation, were removed to the museum (77).

The dig aroused considerable interest in the neighbourhood: the Monmouthshire Merlin reported that

… this district has been kept in continual excitement for some time past, which is not expected to subside very quickly, even after the grand demonstration to take place on Thursday next …

when the Association held its annual meeting at Caerwent. Akerman was on hand to conduct members around the excavations, explaining the significance of each part, after which they repaired to ‘luxuriantly spread tables beneath the apple trees, at a fitting distance from the dusty ruins for a hearty luncheon’(78). The fame of the excavations spread far and wide: the French Ministry of Education wrote asking Morgan to send full particulars, for insertion in the Revue des Sociétés Savantes (79).

So successful were the 1855 excavations at Caerwent that the society intended to continue them in subsequent years, but nothing care of the project, partly because sufficient funds were never forthcoming (80). It was not until 1860 that the next excavation took place, during the summer meeting at Penhow. The object was a barrow in a field near the Rock and Fountain Inn. The practice of ‘opening barrows’ had grown into a boom during the previous twenty years, as figures like Bateman, Lukis, Carrington and Thurnam explored hundreds of barrows in Wiltshire, Yorkshire and the Peak District, and few archaeological societies could resist the temptation to raid their local specimens (81). Techniques employed in ‘opening’ barrows had advanced very slowly since the days of Cunnington and Colt Hoare. The Penhow barrow, thirty yards in diameter, was treated in a way usual at the time: a wide trench was dug through the centre of the mound from north to south and excavation continued until the natural ground level was reached. Preliminary work, superintended by Rev. C.W. King, had cleared the area and driven the trench from both sides of the barrow, so that when the members assembled on the afternoon of the meeting only the centre remained unexplored. If they had been expecting dramatic revelations they must have been disappointed, since no burial urn or finds were discovered, with the exception of a broken bronze dagger, a whetstone and some chalk flints. The excavators could not have been blamed. At a time when some of the large-scale barrow archaeologists regularly explored several barrows in a single day, they performed their work carefully over two days and recorded the results (though unfortunately without making detailed plans). They were observant enough to notice traces of postholes at the base of the mound that may have indicated a wooden structure encasing the cremation (82).

Perhaps the lack of spectacular success at Penhow may have played some part in discouraging the society from attempting excavations at annual meetings after 1860. No barrow was excavated until 1888, when an example was dug at Portskewett (83). No excavations of any kind are recorded between 1860 and 1876, when Robert F. Woollett cut a passage into the Castle mound at Caerleon, apparently in the hope that he might be able to prove its prehistoric or Roman origin (84). Roman material now tended to come to light in Caerleon less as a result of deliberate excavation than from chance discoveries during the laying of the town’s drains and sewers in the late l870s and early 1880s. In 1877 Francis Moggridge discovered and carefully preserved a portion of mosaic unearthed in this way, and four years later a watching brief was kept by Canon Edwards during the laying of sewers in the main street, although little of interest was uncovered. Canon Edwards did superintend an excavation in a field north-east of the town in 1881, in the hope of discovering the chapel of the martyr St Aaron, but the results were inconclusive (85). More significant were excavations conducted in 1877-8 by A.D. Berrington near the site of the Court House at Usk. They revealed such a quantity of glass and semi-precious stones that Berrington concluded that he had stumbled upon a jeweller’s workshop. He also discovered a stone commemorating the child of a soldier of the Second Legion, and a tile of the same legion. In his report to the Association he noticed that it was ‘remarkable that none [of the coins discovered] were later than Titus and Vespasian’ (86).

Despite the renewal of excavation activity in the late 1870s, there is no evidence that any digs were initiated or sponsored by the society: all were the private interests of individual members acting on their own initiatives. The hopes of the organisers of the 1855 Caerwent excavation that further work planned and financed by the society could be carried out therefore remained unfulfilled.

5 Publications to 1888

Since the primary aim of the Association on its establishment was to set up a museum in Caerleon, it is understandable that a publication programme appeared less important to its members than it was to the founders of the Cambrian Archaeological Association shortly before. Indeed, the Committee’s report to the 1849 annual meeting assumes that descriptions of discoveries made in Caerleon would be published in ‘one of the archaeological journals, or some eligible work’, rather than by the society itself (87). Next year appeared Lee’s account of the Castle Baths excavation, issued not by the Association but by a London publisher, J.R. Smith, though with the intention of raising funds towards the establishment of the museum.

In 1852, however, it had apparently become the intention of the society to publish papers read at annual meetings itself, although the first publication did not appear until 1854, with Morgan’s and Wakeman’s papers on Caldicot Castle (88). This volume, adorned with Lee’s illustrations, was distributed free to members at the annual meeting in 1854. A limited number were also printed for general sale at 5s 6d each, in the hope of using the proceeds to help pay off the Association’s outstanding debt, but the sales must have been disappointing, because a sum of £8 13s 9d was later recorded in the expenditure column of the annual statement of accounts as ‘loss on Caldicot volume’ (89). Clearly publications must henceforth be regarded as desirable in themselves, not as a source of extra revenue.

Perhaps discouraged by the financial failure of the 1854 volume, Lee and his associates drew back from issuing a volume in the next year, originally intended to contain papers by Wakeman on Pencoed Castle and Morgan on St Woolos Church, Newport (90). But the spectacular discoveries at Caerwent in 1855 could not go unrecorded and the opportunity was taken to reprint Morgan’s original report published in Archaeologia, with the addition of some extra material on the history of Caerwert. No volume was published in 1857, but several lithographs of ‘the principal features in the district’, presumably by Lee, were distributed to members, together with facsimiles of a letter from Edward Herbert to Capt. Thomas Morgan, written in 1645 (91). An improved financial position allowed the publication of a volume the following year, again by Wakeman and Morgan, in the preface of which may be found the first statement of publication policy the Association had yet made:

They [the Committee] believe that it will be considered by the members, as a proper application of the funds of the society, to rescue from oblivion … remains of buildings either little known or likely to go to decay; and it is their intention, whenever the funds of the society will allow of it, to print illustrated notices of some of the military, ecclesiastical and civil ruins of the district (92).

The present volume, on churches at Runston, Sudbrook, Dinham and Llanbedr, was intended as the first of a series on each of the ‘military and ecclesiastical divisions’, but it was recognised that a regular and frequent cycle of publication would be possible only if the society’s funds were improved, for example by an increase in membership. After paying for this volume, the Association still had a favourable balance in its accounts. In 1859 a pamphlet by Wakeman on the Augustinian monastery at Newport was issued, followed by further short publications by Wakeman and Morgan, on domestic architecture, in the two succeeding years (95). Indeed, the society managed to Keep up an annual publication cycle, with one exception, until 1868, thanks to a stable subscription income and the relative absence of expense on museum repairs, a cycle which included the Association’s most ambitious book, Lee’s Isca Silurum. All the publications are distinguished by scholarly writing and by the quality of their illustrations: outstanding among the illustrations is a coloured reproduction of the ‘labyrinth’ mosaic in the 1866 volume; photographs also made their appearance, the first being one of the fine Pencoyd family tomb at Llanmartin Church in the 1864 volume: the Committee trusted that ‘the members will consider this expenditure a proper one, as it is desirable to have a perfectly accurate representation of so singular a monument’ (94).