It’s been a writing year rather than a reading one, but as usual I’ve found so much to enjoy in books, many of them happened on by accident, often in charity shops. The book club I belong to also threw up plenty of good reads, including the best novel I’ve read this year, Claire Keegan’s Small things like these. It left such a strong impression on us all that we were left with nothing to disagree about (disagreeing is normally what keeps us going in the club).

Werner Herzog, Every man for himself and god against all (2023)

John Wilson recently interviewed Werner Herzog on the radio. Not unnaturally, he wanted to talk about Herzog’s long career as a maker of feature and documentary films. Herzog, though, insisted that he wasn’t a film-maker, he was primarily a writer, that he wished to be remembered as a writer, not as a director, and that he didn’t want to discuss his films. For some minutes the interview got nowhere.

I suspect that Herzog is wrong – Aguirre Wrath of God will always stand as the last word on Adolf Hitler and one of the greatest films of the twentieth century – but it’s true that his writings are always worth attention, especially his short travel narrative Walking in ice. His most recent book in English is an informal autobiography (he calls it ‘a memoir’). It confirms what Herzog students have always known, that he’s a person drawn to extremes of nature and of human behaviour. There’s plenty here on the perils of filming Aguirre and Fitzcarraldo in South American jungles, on hypnotising the actors in Heart of glass, and on working with actors like Bruno S. and the violent and unpredictable Klaus Kinski. In the early chapters he describes his experiences as a young child in a remote, mountainous part of Germany during and after the Second World War, and how he taught himself the art of film-making from scratch, having fallen in love with the medium. At the end of the book is a filmography that occupies many pages, as well as a list of the operas he’s directed.

What’s less expected, maybe, is that Every man for himself is such a funny read, full of droll stories, many told against himself, and good jokes. A chapter called ‘Unrealised projects’ catalogues a list of bizarre filming plans that came to nothing, including a film on the boxer Mike Tyson and his encyclopaedic knowledge of the early Frankish kings, and another about twin sisters from Yorkshire who mirror their every movement. He also recalls his voiceovers on several episodes of The Simpsons, including a hilarious appearance in Springfield as Walter Hottenhoffer, a demented and suicidal pharmaceutical salesman.

Delyth Jenkins, Mynd i weld Nain (2023)

‘In memory of my parents, Nain and Taid of this story’ is the epigraph of this new short tale for young children, ‘Going to see Nain’. It’s a very personal one, with a wistful, nostalgic tone. It recreates the car journeys Delyth Jenkins took with her two young daughters from Swansea to see her mother in north-east Wales (hence Nain rather than Mamgu). In her cosy bungalow in the middle of the country, within sight of the hills, Nain specialises in offering her visitors endless biscuits, cakes and chocolate buttons. The bungalow seems like a ‘Aladdin’s cave’ to the children, with its drawers full of ribbons and old photos – of their mother as a girl and their two uncles (‘that’s odd, they don’t have any hair now’).

The journey in a hard winter causes anxiety to their mother, but the girls plead with her to stop the car and let them play in the roadside snow. She’s reluctant, but gives way, and three throw snowballs at one another. At Nain’s, more fun awaits them: a delicious tea, a snowman, looking forward to Siôn Corn while sitting on Nain’s bed. On Christmas Day the three of them walk in the hills before sandwiches and jelly back at Nain’s.

There’s a delicate sense of loss and time passing. Taid is absent, but remembered for his love of bird-watching, fishing, tomatoes and sweet tooth. ‘He would have bought you ice creams’, Nain assures the girls.

Mynd i weld Nain picks up some of the themes of Delyth’s first book, That would be telyn, in which family recollections often break through the narrative of a harp-laden walk round the coast of Pembrokeshire. The text is woven around delightful illustrations by Lily Mŷrennyn.

Geoff Dyer, The last days of Roger Federer (2022)

This book appealed for two reasons. First, it’s by Geoff Dyer, who has never, as far as I can tell, written a boring sentence in his life, and second, because it’s about time running out, mainly for creative and sporting people. ‘Last things’ is a well-worn theme, as is ‘late style’, but Dyer has such a wide frame of reference, and such a way with words, that he brings fresh insights to almost every page.

Old Geoff Dyer favourites reappear: tennis stars, jazz musicians, films, Nietzsche, D.H. Lawrence (his best book, for me is the one he wrote on failing to write a book about D.H. Lawrence) and others. And then there are new themes, like attending the Burning Man Festival, American paintings of buffalo, the late poems of Philip Larkin, and, of course, his great hero, Roger Federer: as Federer fades from view, ‘the reign of beauty is coming to an end’. As usual, there’s plenty about Dyer himself, specifically on his age-related declining ability to play tennis.

The most poignant paragraph in the book concerns the painter Willem de Kooning, ‘who enjoyed a sudden surge in productivity, averaging almost a painting a week – a cause for celebration that was also a source of concern.’ He was ‘no longer quite himself’, and turned out to be in the first stages of Alzheimer’s. Later, ‘assistants would project drawings onto canvas for him to paint over and around, line up tubes of paint … and point him towards parts of the canvas – ‘holidays’ was their agreed term – that he’d forgotten to fill in.’

But wit generally triumphs over gloom. Here’s Dyer on writing: ‘ “I finished my book!” I wrote to a friend. Now, after six months of doing almost nothing, I wonder if I got that the wrong way round. Has it finished me?’

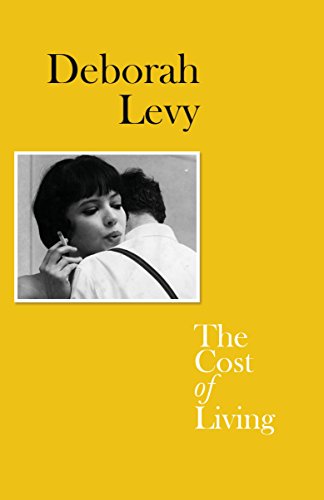

Deborah Levy, The cost of living (2018)

I’ve come late to Deborah Levy, and began in the wrong place, with the second volume of her ‘living autobiography’, a trilogy of books about being a writer and a woman. It’s a handsome book, with a yellow dust wrapper featuring a still of Anna Karina from a Jean-Luc Godard film, and it was a serendipitous find in the Tenovus shop. Its previous owner, ‘Caroline’, bought it new in April 2018. I wonder why she concluded she could do without it?

At the start, the narrator’s marriage has ended, and the family house is sold. What comes next, at the age of fifty? Levy’s writing is precise, economical and unexpressive, but it talks of things that cut to the heart. Here she is on the life she’s just left:

To strip the wallpaper off the fairy tale of The Family House in which the comfort and happiness of men and children have been the priority is to find behind it an unthanked, unloved, neglected, exhausted woman. It requires skill, time, dedication and empathy to create a home that everyone enjoys and functions well. Above all, it is an act of immense generosity to be the architect of everyone else’s well-being. This task is still mostly perceived as women’s work … To unmake a family home is like breaking a clock. So much time has passed through all the dimensions of that home.

She moves into a freezing small flat with one of her daughters, but her life becomes ‘bigger’. She rents a writing shed, ‘calm and silent’, buys an electric bicycle, and starts to live. Living without love is hard. She notices a council notice, ‘this fountain has been winterised’’: ‘I reckoned that is what had happened to me too’. A new blow is her mother’s death, which causes a loss of orientation. And yet she survives. A new life might be in store.

Jasmine Donahaye, Birdsplaining (2023)

I started reading another charity shop book, about being a birdwatcher, Tim Dee’s The running sky. I could tell it was impressive, the work of many years, but I couldn’t get to the end; the writing was overloaded with poeticised language, too much specialised knowledge, and heavy doses of ‘significance’.

Birdsplaining is very different: short, spare and questioning. It’s a collection of essays on different aspects of birds and observing them, linked by a feminist perspective (birding, or at least writing about it, being a largely masculine pursuit). Jasmine Donahaye sets the tone in the first sentence, where she writes, ‘Birds explain nothing to me. I am often unsure what they are or why they matter. The presiding mode in this book is therefore inevitably one of uncertainty.’ Her only expertise on birds is her own experience. This gives the book a refreshing lack of authoritativeness.

The second chapter is typical of her unusual approach. It concerns published field guides to birds. Donahaye points out an obvious but completely overlooked feature of the more traditional of these books – that for any given bird the male is always illustrated and described first, while the female is (literally) overshadowed or obscured or demoted by her mate. Males, of course, are often brighter and more distinctive than females. All the more reason, then, you’d think, for a guide to pay more attention to the female, to aid what can often be quite difficult identification. But males are usually the focus of attention. ‘By extension, it’s no surprise, I suppose, that I find it difficult to see the equal value of my own life, or any woman’s life, when viewed through such familiar and easily recognisable patterns.’

Other subjects include a dead sheep, birds inside her home, puffins and gannets. Donahaye’s acute sense of place – she lives near the great bog, Cors Caron – gives the essays a wonderful coherence.

An earlier version of Birdsplaining won the New Welsh Review’s New Welsh Writing Award. NWR has just had its long life ended by the Books Council for Wales’s decision to abolish its grant – an act of gross cultural vandalism.

Stuart Evans, First impressions (2023)

I should declare an interest: I’ve known Stuart Evans for over fifty years. He’s best known as an artist, printmaker and designer, and this is his first book, which he describes as a ‘fictional memoir’. He’s produced it himself, with the help of the Friends of Ceredigion Museum. Using light disguises, he follows over the course of a year some of the people, including himself, who were in or around the Museum in its early days, the 1970s.

The Museum is overseen by ‘The Curator’. (Many Aberystwyth people will remember him, and the Museum’s first home, a terrace house in Vulcan Street near the Castle.) He’s an old-fashioned and eccentric character whose pastimes are repairing clocks and scraping the sides of his ancient Mini Clubman. The other staff are sometimes younger but equally unpredictable. They include Mrs T., the Museum secretary, ‘Gary’ and ‘Rick’, the handymen, and ‘Steve’, the Assistant Curator, who makes only an occasional appearance in his place of work:

Ring ring

‘He can’t come today. He can’t move because of his bad back.’Ring ring

‘He can’t come in today. There are severe floods between here and the museum.’Ring ring

‘He can’t come in today. He can’t hear anything I say.’Ring ring

‘He can’t come in today. We’ve had a disaster in the kitchen. I was drying by tights under the grill and they caught fire.’

Stuart himself, the Museum’s technician, designer and brass-polisher, is a participant in the Museum’s stories, but his main role is as an amused observer. The book’s a droll, lightly-plotted tale, and evokes a time when two cultures collided: the mainly Welsh-speaking world of the native Cardis, and that of the artists, musicians, misfits and loners blown in from England and elsewhere. Towards the end, the Museum’s due to migrate to where it is now, the old Coliseum theatre: a second place of make-believe and fiction.

Leave a Reply