Has a song title ever said so much in so few words? This one has the reputation of being one of the oldest blues songs. That’s a claim that’s hard to substantiate, but this song certainly has a long history, and it’s still alive and well today.

‘Poor boy long ways from home’, often shortened to ‘Poor boy’, tells of a universal, timeless experience – of homesickness, lostness and lonesomeness, being on the borders of destitution. But within its blues context it has a more specific meaning, because in the first half of the twentieth century black people in the southern states so often found themselves on the road and a long way from where they started. For many, staying at home was synonymous with poverty and oppression. Travel, on the other hand, carried the hope of a better life, a relief from racial discrimination, or at least a better paid job. For many, wandering mutated into larger-scale migration, from the cotton fields of the south, along the railroads, to Chicago, Detroit and New York. In these urban centres black workers could earn more, and escape, if not from segregation, at least from the worst aspects of racial oppression. Musicians naturally moved around more than most, in search of new audiences.

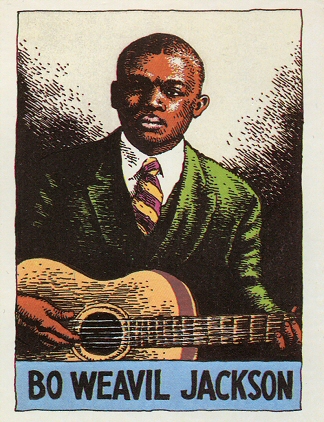

The UK blues scholar Paul Oliver tried to trace part of the lineage of ‘Poor boy long ways from home’ in his pioneering history, The story of the blues. He doesn’t, though, mention the earliest recorded version of the song, made on 30 September 1926 in New York City. This date makes it one of the earliest country blues recordings ever made. The artist was ‘Sam Butler’ (his real name may have been James Butler), otherwise known as Bo Weavil Jackson. He was an obscure figure, and little is known about him beyond his two recording sessions, in Chicago and New York, in 1926.

Butler plays slide guitar and a tune that was clearly already well-established, but his guitar work is sparse and staccato, and his voice is hesitant. The words are more generic than later versions (and he sends a letter home, rather than placing a phone call):

I woke up this mornin’, blues all ’round my bed

I woke up this morning, mama, blues all around my bed

Thinkin’ about the words that my brown had said

‘Cause I’m poor boy here, long ways from home

Poor boy here, long ways from my home

Ain’t got nowhere, Lord, to lay my head

A slightly later, much more accomplished recording was made in Chicago for Paramount Records in 1927 by Gus Cannon, under the name ‘Banjo Joe’. This could be regarded as the ‘definitive’ version, if such a thing were possible in an oral tradition, and it set a high standard for later artists. Born around 1883, Cannon lived in Clarksdale, Mississippi and learned to play the banjo and fiddle. He was best known for the up-beat jug band records he made a little later in Memphis with Noah Lewis and Ashley Thompson as ‘Cannon’s Jug Stompers’. ‘Poor boy’, though, is quiet and reflective. There are just two instruments, banjo and guitar. Cannon plays the banjo, in ‘Vestapol’ (open D major) tuning, with a slide – a brass ring, knife or bottle-neck. A slide was common enough in blues guitar, but very rare or even unique on the banjo. He’s accompanied, inconspicuously, by Blind Blake. Blake was a guitar virtuoso, who could play as fast and creatively as anyone. He’s a shadowy figure: unlike Cannon, who live long enough to be ‘rediscovered’ in the 1950s and 1960s, he died in his 30s.

Banjo Joe (Gus Cannon)-Poor Boy, Long Ways From Home – YouTube

Cannon sings the words:

Been a poor boy an’ a long ways from home

Long way from home

Been a poor boy an’ a long way from home.I got ‘rested, no money to buy my fine,

Money to buy my fine,

I got ’rested, no money to buy my fine.But I guess I’ll have to catch the Frisco out – in this lan’,

Catch the Frisco out,

Lord I guess I’ll have to catch the Frisco out.Man, if that don’t do I’m goin’ … woods a while

Try the woods a while

Yeah …I cried ‘Hello Central, give me …

… your long-distance phone.’

I cried ‘Hello Central, give me your long-distance phone.’[spoken] She ask me what number did I want.

I cried, ‘Please ma’am give me Thirteen-Forty-Nine,

Thirteen-Forty-Nine’

I cried, ‘Please ma’am give me Thirteen-Forty-Nine.’Tried to phone it to m’

Tried to phone it to m’

Tried to phone it to m’

Tell her send me little

Tell her send me little money

Tell her send me little money

Oh, to buy my fine.

She cried, ‘The bucket’s got a’

She cried, ‘The bucket got a’

She cried, ‘The bucket got a

Lord, ‘twon’t hold no beer.’

The key ‘poor boy’ motifs are all here: the danger of arrest in an unfamiliar place, the lack of money, the need to keep moving on, usually by rail (the Frisco line ran from St Louis to San Francisco), the desperate phone calls home. The title, the words and the tune were almost certainly part of the shared song tradition before 1927. Cannon himself, already in his forties when he made his recording, later claimed that an earlier guitarist named Alec Lee had taught him ‘Poor boy’, and how to play slide. Like many blues songs, this one contains syntactic or lexical formulae (‘I got ’rested, no money to buy my fine’, ‘hello Central, give me your long-distance phone’): building blocks of the shared oral tradition that could be lifted from the singer’s memory and slotted into songs as the occasion demanded – in much the same way as the poets of the Iliad and Odyssey, also working in an oral tradition, constantly reused epithets, phrases and whole sentences in multiple contexts. (The ‘bucket got a hole in it’ motif at the end of Cannon’s song is a slightly incongruous import of this kind.) More than likely, ‘Poor boy’ predated the blues and was itself imported (its verses often lack the standard three-line blues form). In an article in 1911 the sociologist Howard W. Odum heard the song in northern Mississippi and noted some its words:

I’m a po’ boy long way from home,

Oh, I’m a po’ boy long way from home.I wish a ‘scurshion train would run,

Carry me back where I cum frum.Central gi’ me long-distance phone,

Talk to my babe all night long.

Barbecue Bob (Poor Boy, Long Way From Home) – YouTube

In the same year as Gus Cannon’s song, 1927, Barbecue Bob (Robert Hicks), a blues singer from Atlanta, Georgia, recorded ‘Poor boy’, to his own slide guitar accompaniment, to the same tune as Cannon’s. The effect is lugubrious and sweet. Some of the motifs overlap with those of Cannon, like the long-distance phone call (Central is asked for Six-O-Nine this time), but other verses are different, and even bleaker:

Ain’t got nowhere to lay my worried head

Hon, ain’t got nowhere to lay my worried head

I ain’t got nowhere lay my worried head

Some time I soon to be dead.

Ramblin’ Thomas-Poor Boy Blues – YouTube

In 1928 a fourth ‘Poor boy’ appeared, again on the Paramount label, by Ramblin’ Willard Thomas. His recording is very different from the two 1927 versions. The tune is recognisably the same, but only just, because Thomas’s guitar treatment is spare and minimal, and his voice slow and melancholy. The lyrics are new. The river boat replaces the railroad to take the singer ‘long ways from home’ (from Louisiana to Texas), and water is his ruling element:

I don’t care if the boat don’t never land

I like to stay on water as long as any manAnd my boat come a-rockin’ just like a drunken man

And my home’s on the water and I sure don’t like land

Later country guitarists took up the ‘Poor boy’ song, with the kinds of variations in tune and wording that were natural in the blues. The folklorists John and Alan Lomax collected several versions. In 1935 they recorded Gabriel Brown, and in 1959, in the Parchman Farm penitentiary, they found an obscure musician called John Dudley, a slide guitarist who sticks closely to the tune. Mississippi Fred McDowell sang a version, again with the traditional tune, in which he reduces each verse to a single first line, letting his slide guitar fill in the remaining two lines. Starting slow, the pace of the song gradually speeds up, like the train McDowell mentions:

I’m a poor boy, long way from home

Poor boy and a long way from home

I’m worried, baby, and I won’t be worried long

Well, it’s train time here, tracks all out of line

Keep me worried, bothered all the time

I’m gwine somewhere, don’t know where I’m gwine.

The ‘classic’ version of ‘Poor boy’ clearly lived long in the memory of country singers, and was often sung by them years later, after they were ‘rediscovered’. Robert Pete Williams kept to the same tune, and sang it, in a thoughtful, halting style, as ‘Poor Bob’s blues’, when Harry Osler recorded him in the late 1950s after finding him in Angola State Penitentiary. Similarly, Cat Iron , also recorded in the 1950s, sang his own words (‘Ain’t got nobody to feel and care for me / Says, all I had done caught the train and gone’). Herman Johnson, recorded in 1961, revives the motif of the ‘long-distance call’. In his 1976 recording Eugene Powell (‘Sonny Boy Nelson’) keeps very close in its musical detail to Cannon’s, almost fifty years before. Other singers were John Jackson in 1969 and Peg Leg Sam, accompanied by Louisana Red on harmonica, in 1975. One of the most distinctive of these later recordings is one by James Henry Diggs, made in 1962 (he’d originally been recorded for the Library of Congress in a penitentiary in 1935):

I got a ship on the ocean, goin’ ’round and ’round

Lord, I got a ship on the ocean, goin’ ’round and ’round

I got a ship on the ocean, going ’round and ’round

Before the gal of mine leave me, I’d jump overboard and drown.

I said, take me, baby, put me in your big brass bed

Oh Lord, take me, mama, put me in your big brass bed

I said, take me, baby, put me in your big brass bed

Let me lay there, baby, ’til my face turn cherry red.

Other singers, though, took the tune in quite different directions. Bukka White recorded ‘Po’ boy’ in 1939 for Alan Lomax in Parchman Farm. His approach is to abstract from it a swinging rhythm close to dance.

He lays his steel guitar on his lap (see the later filmed version) and attacks the strings with his fingers and metal slide in the energetic, percussive style he was famous for. The effect is viscerally powerful and a long way away from the quiet lyricism of Gus Cannon and the earlier singers. In effect, this is a wholly new song. A very different singer, from the wider songster rather than the blues tradition, was Mississippi John Hurt. In his recording of ‘Poor boy’, made for the Library of Congress in 1963 shortly after his ‘rediscovery’, he plays and sings in his usual soft manner, but keeps nothing of the words or the tune of the usual song: only the title remains. Similarly, R.L. Burnside, recorded in the field by Alan Lomax in 1978, makes the song his own, playing a slide-less guitar with an upbeat riff and using his own words.

At the end of his recording Burnside implies that he picked up the song, ten years earlier, from Howlin’ Wolf. This rings true, because his song is a stripped-down version of ‘Poor boy’ as sung by Wolf, and it uses the same lyrics, which, like the tune, have little in common with those of the 1920s recordings. Wolf first released his ‘Poor boy’ song in 1958 for Chess Records. It features his gravelly shout and harmonica, and his usual tight band, including Hubert Sumlin on electric guitar. But Wolf seems to have been an exception. Otherwise, ‘Poor boy’ didn’t translate well from the South to the amplified clubs of Chicago. Perhaps its theme of loss and wandering didn’t appeal to those who’d found a new, permanent home in the north. Or maybe it was just regarded as too ‘old-fashioned’ for the new electric world.

John Fahey – Poor Boy – YouTube

The blues revival that began in the 1960s encouraged many white artists to excavate different strands of the ‘Poor boy’ tradition. The Black Keys took their lead from Howlin’ Wolf and R.L. Burnside. Jeff Buckley, in his song recorded in 1993, returned to Bukka White: his version faithfully preserves White’s driving steel guitar sound. And John Fahey, for my money by far the best of the revivalists, went all the way back to Gus Cannon and Barbecue Bob for his ‘Poor boy long ways from home’. It’s included on his first commercial album, The transfiguration of Blind Joe Death, released in 1965. (There was an earlier limited edition version, which, astonishingly, features Fahey’s voice: he was famously silent on all his later records).

Fahey picks a solo guitar, without slide, and of course omits the words. Except that we hear a dog barking at the start: Fahey whispers ‘Shh, shh!’ and the tune resumes. This is a reverent tribute to the great masters of early country blues, recalling their melancholy wistfulness. But it’s also imbued with the unique, unmistakable aura of John Fahey’s own musical personality. It’s one of his earliest and finest tracks.

Note For a list of ‘Poor boy’ recordings see the Weenie Campbell site and associated thread.

Leave a Reply to Andrew Green Cancel reply