When he was 21 years old Samuel Taylor Coleridge came to Wales for a walking tour with his Cambridge friend Joseph Hucks. In a letter written in Denbigh in July 1794 to Robert Southey he summarises the trip so far, and writes,

From Bala we travelled onward to Llangollen, a most beautiful village in a most beautiful situation. On the road we met two Cantabs of my college, Brookes and Berdmore. These rival pedestrians—perfect Powells—were vigorously pursuing their tour in a post-chaise! We laughed famously. Their only excuse was that Berdmore had been ill.

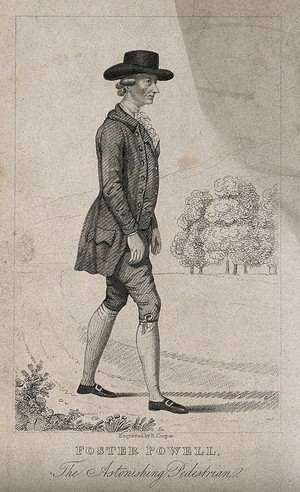

This captures perfectly the disdain the committed walker feels towards wheeled travellers. But who was this famous pedestrian ‘Powell’? His full name, it turns out, was Foster Powell, and he was one of the earliest pioneers of long-distance walking in Britain. Today, sadly, he seems almost completely forgotten. Rebecca Solnit makes no mention of him in Wanderlust, her detailed history, and he’s similarly neglected by other historians of moving on two feet.

Powell was baptised in Horsforth, near Leeds, on 12 December 1734. His father was William Powell (b. ?1706), and presumably his family was originally Welsh. In 1762, after a period of alleged ‘obscurity’, he moved to London, where he worked as a clerk to a Temple lawyer. Then he lived with, and worked for, his uncle in New Inn. He was reported to be ‘a quiet inoffensive lad, shy, and somewhat unsocial, with nothing in the faintest degree remarkable in him’ – except for his extraordinary appetite for walking long distances, often for a wager (pedestrianism developed as a betting sport, using the legs of humans rather than those of horses or dogs).

Powell started his pedestrian career in 1764 by walking 50 miles along the London to Bath road in seven hours, ‘although encumbered with a great coat and leather breeches’. Much later, in 1786, he covered a hundred miles on the same road: ‘this performance caused much noise in London and made his fame spread abroad as a pedestrian’. He travelled to France and Switzerland, where he ‘gained attention by his remarkable walking power’. In November 1773 he upped his game, walking 402 miles from London to York and back, in five days and eighteen hours. He repeated this feat in 1778, 1790 and 1792, when he was 58 years old. On this final occasion he arrived at York Minster after just five days, fifteen hours and fifteen minutes, surpassing his earlier times. In 1787 he walked from London Bridge to Canterbury (122 miles) and back in 24 hours, ‘to the astonishment of some thousands of spectators, who were waiting with anxious desires for his safe arrival’, and repeated the route the next year, at a faster time. Though he lost his bet after taking the wrong turning at Blackheath on the return leg, his friends took pity on him and made him a donation of £40. Powell also had a side-line in running, though here he was less accurate in his forecasting: in 1778 he attempted to run two miles in ten minutes, but lost the wager by half a minute.

Powell was ‘tall and thin, about five feet nine inches high, very strong downwards, well-calculated for walking, and of rather sallow complexion’. He slept for only five hours each night. He preferred ‘light food’ and seldom if ever ate meat on his journeys. He generally took no liquor, though he did resort to some brandy on his walks. He was ‘of a mild disposition, possessed of many valuable qualifications, and discharged himself with fidelity and sobriety’.

He developed a wide reputation as a long-distance walker, and crowds would turn up to see him at the finish. But his walking feats clearly failed to make his fortune. The Gentleman’s Magazine, noticing his death, remarked

His extraordinary feats of walking, by which he might, with proper management, have profited so much, never produced him enough to keep him above the reach of indigence. Poverty, which he ought always to have kept a day’s march behind him, was his constant companion in his travels through life, even to the hour of his death.

In 1793 Powell suffered a sudden illness, attributed to the effects of his last, heroic walk to York and back. He died ‘in rather indigent circumstances’, aged fifty-nine, at New Inn on 15 April 1793. Naturally the funeral procession, from New Inn, along Fleet Street and up Ludgate Hill, was on foot, and he was buried outside St Faith’s Church, next to St Paul’s Churchyard.

After his death an anonymous pamphlet was published to mark Powell’s achievement. The preface states,

In all ages there have been men who have distinguished themselves in some particular manner from the bulk of mankind. I may say few have caused more notice than the deceased, who was without partiality the greatest Pedestrian ever known in England and singularized himself as such for upwards of thirty years.

The obituary continues by painting an attractive picture of Foster’s character:

… he never shewed that he thirsted for money, nor was he avaricious; had this been the case, there is not a doubt but he might have gained some thousands; but he was content with a little, and felt a secret pleasure in being able at all times to fulfil his engagements.

Pierce Egan, the nineteenth century sports writer, called Powell ‘a pattern to all pedestrians for unblemished integrity; in no one instance was he ever challenged with making a cross’. (‘Making a cross’ was a slang term for cheating.)

Competitive walking for money flourished in the nineteenth century. Its most famous exponent was Captain Robert Barclay Allardice, noted for walking a mile every hour for 1,000 successive hours in 1809. The sport didn’t survive into the twentieth century: by now there were other, more convenient ways of encourage others to lose money through gambling. For us, long-distance walking tends to have less in common with the Stakhanovite feats of Foster Powell, and more with the nature-centred practice of Wordsworth and Coleridge.

Leave a Reply