These days chaos as a concept has been captured by mathematics and physics. (Sometimes it gets re-exported to the popular imagination through tropes like the butterfly effect.) But before that it was available to anyone. It was especially attractive to philosophers, theologians and mystics, and to creative people like writers and artists.

Chaos has always been a problem to writers and artists. How do you encompass in ink or paint, on paper or canvas, something that’s by its nature unordered and boundless? John Milton, undaunted (one of his favourite words) by a challenge, gives it his best shot, towards the end of Book II of Paradise lost.

There must be many readers of Paradise lost, like me, who start reading the poem (aloud, as Philip Pullman advises), slowly and uncertainly at first, only to be drawn in and gradually overwhelmed by the powerful pentameter rhythms, the clash of language (spare Anglo-Saxon and lofty Latin) and the heroism of Milton’s Satan.

Satan has arrived at the borders of Hell and persuaded Sin and Death to open its great gates of brass, iron and adamantine rock, so that he can seek out the world of the newly rumoured humans and gain his revenge on the Almighty Power. He stands on the threshold of Chaos and looks down into the abyss:

Before thir eyes in sudden view appear

The secrets of the hoarie deep, a dark

Illimitable Ocean without bound,

Without dimension, where length, breadth, & highth,

And time and place are lost; where eldest Night

And Chaos, Ancestors of Nature, hold

Eternal Anarchie, amidst the noise

Of endless Warrs, and by confusion stand.

For hot, cold, moist, and dry, four Champions fierce

Strive here for Maistrie, and to Battel bring

Thir embryon Atoms; they around the flag

Of each his faction, in thir several Clanns,

Light-arm’d or heavy, sharp, smooth, swift or slow,

Swarm populous, unnumber’d as the Sands

Of Barca or Cyrene’s torrid soil,

Levied to side with warring Winds, and poise

Thir lighter wings. To whom these most adhere,

Hee rules a moment; Chaos Umpire sits,

And by decision more imbroiles the fray

By which he Reigns: next him high Arbiter

Chance governs all. Into this wilde Abyss,

The Womb of nature and perhaps her Grave,

Of neither Sea, nor Shore, nor Air, nor Fire,

But all these in thir pregnant causes mixt

Confus’dly, and which thus must ever fight,

Unless th’ Almighty Maker them ordain

His dark materials to create more Worlds,

Into this wild Abyss the warie fiend

Stood on the brink of Hell and look’d a while,

Pondering his Voyage: for no narrow frith

He had to cross.

This passage is so brilliantly written it usually makes readers stop, reread and wonder. Dozens of books, article and theses have been written on where Chaos sits in Milton’s cosmic world. Maybe the real answer is, it doesn’t. It’s certainly outside geography, and outside time: ‘a dark / Illimitable Ocean without bound, / Without dimension, where length, breadth, & highth, / And time and place are lost’. It’s a place (or no-place) but also an agency: Chaos is a figure, an ‘Umpire’, presiding over ‘eternal Anarchie’. Anarchy means endless conflict between warring forces, conceived of partly as soldiers (the Civil Wars were still a living memory), partly as microscopic elementary particles (‘embryon Atoms’) bumping into one another. Chaos the Umpire isn’t there to calm the combatants but to give the battle fresh impetus (‘imbroiles the fray by which he reigns’).

Where does Milton’s chaos sit in his moral universe? In his 1963 article on the subject A.B. Chambers claimed baldly that Chaos and Chance ‘are the enemies of God. The fact is sufficiently obvious to most readers’. But is it so clear cut? The phrase ‘the Womb of nature and perhaps her Grave’ suggests chaos is a primordial reservoir of future life, or even a quarry from which God himself can make stuff anew: ‘unless th’ Almighty Maker them ordain / His dark materials to create more Worlds’. Milton poses these complicated questions before abruptly returning to the ‘warie fiend’ on the brink of Hell. A little later Satan encounters the enthroned Chaos, the ‘Anarch’ (a Milton neologism), and asks for directions to earth, ‘this pendent world’. Chaos the character is more partisan than chaos the element. He wishes Satan good speed, with the parting comment, ‘havoc and spoil and ruin are my gain’.

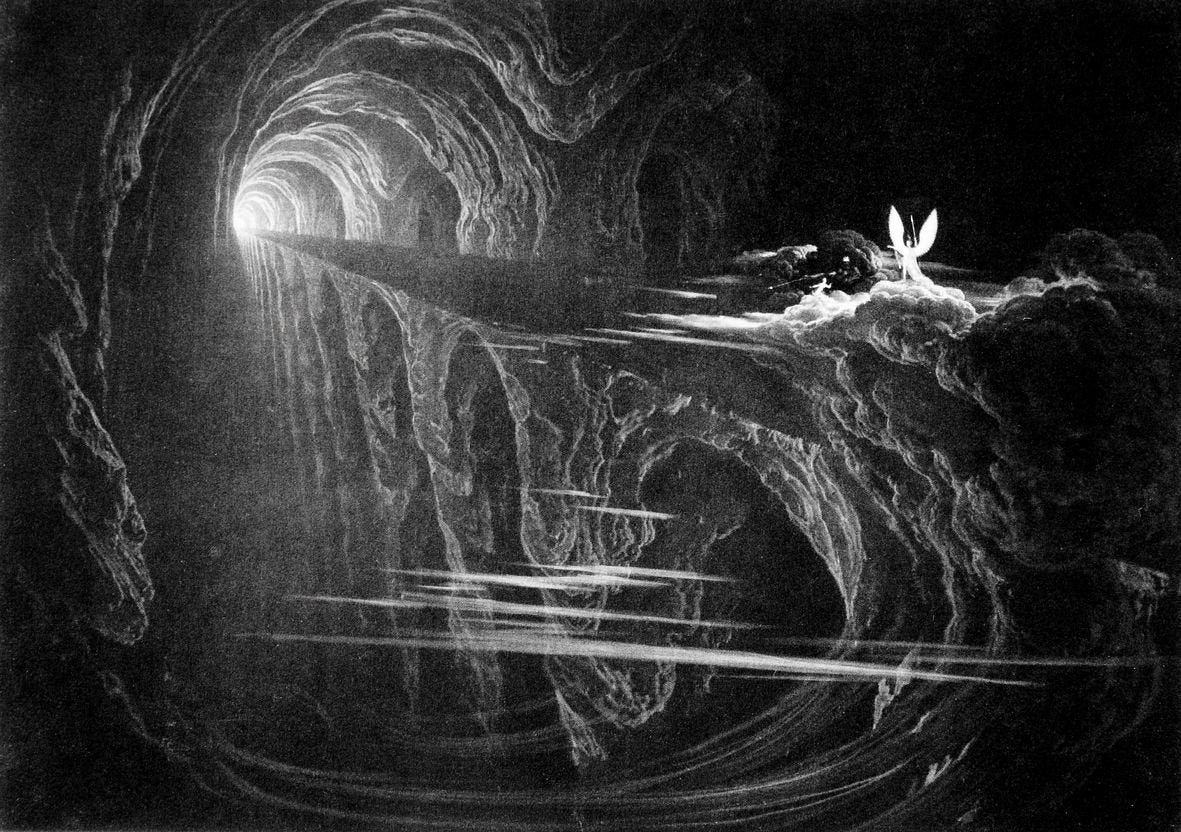

Many artists since Milton have illustrated scenes from Paradise lost, but understandably few have chosen the theme of Satan observing the land of chaos. William Blake avoided the scene. James Barry drew Satan at the throne of Chaos for an unfinished painting. Gustave Doré engraved the flight of the winged Satan through a far too solid chaos, and John Martin imagined the bridge Satan used to cross the abyss. Not one comes close to producing a visual equivalent of Milton’s vivid, ambiguous, complex words.

There’s a quite different approach to picturing chaos, which avoids figurative illustration altogether. A pre-Miltonic example occurs in the work of Robert Fludd (1574-1637) an esoteric writer on cosmology, medicine and astrology. In his multi-part work Utriusque cosmi …. historia, published between 1617 and 1620 – Milton, who was nothing if not bookish, may have read it as a young man – Fludd discusses what existed before the beginning of the world, and on p.26 includes an astonishing image – a large, entirely black square with identical wording around each of its edges, ‘et sic in infinitum’ (and so on to infinity). Black, you’ll notice, not white, in line with Milton’s insistence on ‘eldest Night’, and with current astrophysical language (black holes, dark matter). Fludd talks of an original condition ‘without quantity or dimension, since one can speak of neither small nor large; without qualities, neither rarified nor compact, imperceptible; without properties or tendencies, neither moving nor still, without any colour or elemental characteristics; passive initially yet capable of all actions and [of becoming] all things’. He also speaks of ‘the place where Cold and Wet fight with Heat and Dryness’.

A further diagram on p.29 illustrates a later phase, showing the diffusion of the light of intelligence through the primordial stuff, from the centre towards the circumference of a circle, like a flower in a paperweight.

Fludd’s black square makes a comeback every so often in later art. Two examples that come to mind immediately are the black rectangle, a metonym for the death of Yorick in volume 1 of Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy (1759), and Kasimir Malevich’s pioneering Black square on a white ground of 1914-15. Malevich once said, in unconscious echo of Fludd and Milton, ‘I transformed myself in the zero of form and emerged from nothing to creation’.

Leave a Reply