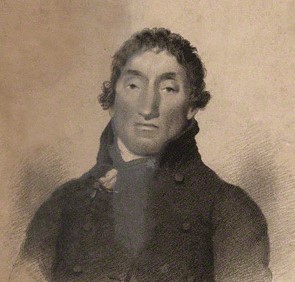

(early 19th century engraving)

In his time Foster Powell was known for mighty feats of pedestrianism. But his achievements pale in comparison with those of a rather younger contemporary, John ‘Walking’ Stewart (1747-1822). While Powell’s stage was mainly limited to England and Scotland, Stewart walked over large parts of the globe. As well as his wanderings he was known in his lifetime for his eccentric philosophical thinking, set down in books with titles like Roll of a tennis ball through the moral world (1812).

Stewart was a Londoner, born to Scottish parents. They were well enough off to send him to Harrow School, where, according to an obituary, ‘he was only remarkable for his inattention to learning, being looked upon as the biggest blockhead in the class to which he belonged’. They moved him to Charterhouse School, where he proved no better. Later, in an autobiographical sketch, he claimed that ‘the most important action, in the production of happiness, was to uneducate myself, and wipe out all the evil propensities and erudite nonsense of school instruction’.

Finally, his parents sent him to Chennai (Madras) in 1763 to be a clerk in the East India Company, ‘in the hopes of removing his indolent habits’. Here ‘the energy of his mind made the first vigorous effort of development’. He learnt Indian and other languages and conceived a grand ambition: to walk the world, in order to ‘trace the causes of human misery, and the causes of human welfare, and of determining how far the latter might be brought to perfection’.

He was encouraged in his plan by a Persian proverb, ‘human energy increases in the ratio of travel’. He later wrote of the benefits of seeing other cultures, ‘the opposite and contradictory opinions of [other] nations broke the chain of associated ideas and the local prejudices of education were dissipated by the most sudden and powerful shocks of contrasted laws, opinions and customs.’

In Chennai Stewart found the rapacity and corruption of the East India Company intolerable: ‘he considered the internal and external economy of the Company as incompatible with the honour and interests of Great Britain’. He wrote to his superiors taking them to task and resigning his job. Next he went to work for one of the Indian rulers who resisted the Company, Hyder Ali of Mysore, ‘the great and extraordinary barbarian, the Napoleon of the East’. He rose to the rank of a general in Hyder’s military forces, but later fled from Mysore, fearing assassination, and became the private secretary and then prime minister of Muhammad Ali Khan Wallajah, the pro-English nabob of Arcot in southern India.

In the mid-1770s Stewart put his grand walking plan into operation. He crossed India and walked to the Persian Gulf, and on into Ethiopia and central Africa. Back then across Arabia and on through the Mediterranean, until he arrived in London in 1783. A European tour followed in 1784. He insisted on walking, treating other forms of transport with disdain. In London in the early 1790s he would appear in public, in Armenian dress, to share the philosophical thoughts he’d developed on his long journeys. Few people took him seriously, and he decided to try his luck in America. The Americans too proved unreceptive, so he came back to London, and then sailed for France at the time of the Revolution, meeting William Wordsworth in Paris in autumn 1792, just before the execution of Louis XVI. By the mid-1790s Stewart was back in America, walking widely in Canada, the United States and Latin America, giving lectures for money on his philosophical system. He finally received the unpayed salary from his period in Arcot, and he spent his last years more comfortably in London, entertaining in conversaziones in his home whoever was patient enough to listen to him. He died in 1822, aged 75.

Thomas de Quincey knew Stewart well, and wrote about him. He called him ‘one of the lions of London’, and ‘in many respects, a more interesting man than any I have known’ (note the qualification). He conceded that Stewart ‘must have been crazy when the wind was at NNE’, and recalled saying goodbye to him for the last time in a London street: ‘I looked after his white hat at the moment it was disappearing, and exclaimed – ‘Farewell, thou half-crazy and eloquent man! I shall never see thy face again.’’

An anonymous obituary sums up his appearance:

Mr. Stewart, in height, was full six feet: his figure was at once handsome and firm; and his head and features were strictly Roman in their cast. He was endowed by nature uncommon strength, which his pedestrian habits enable him to preserve at an advanced age of life.

He prided himself on his heath routines:

I have (notwithstanding a muscular debility, contracted by the pernicious use of tobacco in smoking) the most perfect state of health, owing to extreme temperance and a particular regard to dress and clothing … I make it a rule to take the temperate exercise of walking two hours before breakfast, and three before dinner, every day … I have had a very dangerous gangrene in my leg, and cured it by a regimen of roasted apples …

He was a vegetarian, and also swore by diluted soap after coition as a ‘venereal preventive’, and mud baths to help appetite and invigorate muscles. But he suffered during his travels: ‘his body bore marks of several desperate wounds by sword and bullet, and the crown of his head was indented nearly an inch with a blow from some warlike instrument.’

His mind was equally remarkable. He mastered eight languages, and was familiar with several more. He was widely read, in the classical and modern writers. He seems to have been a ‘speculative atheist’, or at most a pantheist, with leanings towards atomism. And yet, his biographer implies, Stewart was perverse in insisting on publishing his incomprehensible philosophy in thirty, mainly privately-printed volumes, instead of writing up his travels:

The variety of adventures he met with in the several countries he traversed on foot, must have been highly interesting in their nature, and it is to be lamented that he never committed any of these to paper: this, however, arose from actual design, and not from neglect, as he constantly refused all solicitations on this head from those who wished to collect sufficient information from him to form a memoir of his life. His reply was, ‘that his were the travels of the mind’, and his object the discovery of the polarity of moral truth.

In his autobiography Stewart writes about the benefits of his travels:

In the course of my very extensive travels in all the four quarters of the globe I reaped two inestimable advantages: the increase of intellectual power, and a sovereign control over my passion. I discovered, that the air was the true pabulum of the nervous system …

Stewart’s writings, influenced in part by Eastern philosophies, were, according to another obituary, ‘to most persons wholly unintelligible, and failed in convincing any one’. A modern biographer, Barry Symonds, calls them

… curious compounds of geography, materialist philosophical speculation, extravagant moral rumination, occasional excursions into verse, and sundry unrelated harangues at the reader … Stewart’s intellectual peers designated him a speculative atheist: his philosophical ideal comprises a sort of self-reflexive pantheism, free love, natural democracy, and perfectibilarianism.

Symonds, and other recent analyst like Gregory Claeys and Kelly Grovier, perhaps give too much shape to Stewart’s crazy ramblings. Here, taken at random, is the beginning of a section from Roll of a tennis ball through the moral world:

DAMP BEDS AND SHEETS

The mortal stabs that have been given to many excellent constitutions, by this species of secret murder; and the widows and fatherless children which have been produced by it, as well as the subjects of which the king has been deprived, are far beyond the conception of any private individual – In the course of my travels for the last eighteen months, I have heard of so many deaths and disorders, produced by this kind of injury, that I have censured myself for not preserving regular documents of the facts … More lives have been lost, and more constitutions injured, by damp beds and sheets, than by the overloading of coaches …

‘Walking’ Stewart was not perhaps the greatest advertisement for the mental benefits of pedestrianism. He doesn’t fit into other streams of pedestrianism of his time, either the nature-worship and political performance of Wordsworth and Coleridge, or the competitive commercialism of Foster Powell and Captain Barclay. He has more in common with wanderers nearer to our own time, like the free spirits who set off from the US and UK in the late 1960s for Kathmandu and other remote sites of personal enlightenment.

Despite what Stewart says about the motivation behind his world travels, it’s very curious that he never wrote about them. He was also very reluctant, it seems, to talk about his walking exploits in the course of conversation. The few stories he did tell about them have a worrying implausibility. For example, as he was crossing the Persian Gulf the Muslims manning the boat blamed him, as an infidel, for a storm that arose, and decided to throw him overboard; he saved himself by successfully persuading them instead to hang him in a hen-coop from the main-yard till the storm abated. No independent contemporary accounts survive that corroborate this story, or indeed any part of his travels.

Could it be, I wonder, that John Stewart’s world-walking was a complete fantasy – self-publicity aimed at building his celebrity status and attracting an audience for his eccentric philosophical teachings?

Endnote

There is a curious connection between Stuart and another prodigious walker of the period, Edward Williams, or ‘Iolo Morganwg’ (1747-1826), the Welsh ‘rattleskull genius’ known as a political and religious radical, poet, cultural inventor and forger, and antiquarian. Elijah Waring, in his memoir of Iolo, describes an early morning walk he made from Oxford to London, where he fell into conversation with some men.

On his replying to some inquiries, that he had just walked up from Oxford, which he had quitted that morning, several persons expressed their incredulity, when an elderly gentleman, who sat reading in a corner, on hearing the conversation arose, and requested the Bard to walk a few steps at his usual pace. When this gentleman had observed his gait, the form of his legs, and the relative position of his knees and ankles whilst standing erect, he pronounced that Williams was a likely man to have walked the distance in question that day, without any appearance of fatigue: and this opinion was received by the doubters as decisive, the gentleman being no other than the ingenious and celebrated Mr. James Stuart, commonly called Walking Stuart, who was one of the first pedestrians in the kingdom , and therefore good authority on the subject.

Leave a Reply