Today is industry day. We’re back in Talacre, after a pair of slow bus rides, and plan to reach Flint. It’s even colder this morning – it sleets for a time later – and we’re dressed as if for the Norwegian Arctic. This time we do call in at Lola and Suggs for a coffee. Lola (or possibly Suggs) apologises for the lack of daily papers; previous customers had a habit of stealing them, so now she displays only out-of-date ones.

Today is industry day. We’re back in Talacre, after a pair of slow bus rides, and plan to reach Flint. It’s even colder this morning – it sleets for a time later – and we’re dressed as if for the Norwegian Arctic. This time we do call in at Lola and Suggs for a coffee. Lola (or possibly Suggs) apologises for the lack of daily papers; previous customers had a habit of stealing them, so now she displays only out-of-date ones.

We set off eastwards, a strong wind at our backs and marshland on the seaward side. The sea – about to become the Dee estuary – is a rusty brown colour. Before long we get to Point of Ayr (Y Parlwr Du) and the empty site of the famous colliery, which only closed finally in 1996, after over a century of working. At its peak it employed 839 men, and pit ponies were in use there until 1968. Galleries extended far out to sea, over 1,000 feet below the surface. Nothing remains of the mine on the site, except for traces of rail track and the dock from which coal was exported by ship. On part of the site is a gas terminal, a complex tangle of pipework and towers burning surplus gas, which feeds Connah’s Quay power station. Further on, by the side of the road outside the village of Ffynnongroyw, the head-frame and winding wheel of one of the shafts have been re-erected as a memorial to the generations of miners who worked there.

We set off eastwards, a strong wind at our backs and marshland on the seaward side. The sea – about to become the Dee estuary – is a rusty brown colour. Before long we get to Point of Ayr (Y Parlwr Du) and the empty site of the famous colliery, which only closed finally in 1996, after over a century of working. At its peak it employed 839 men, and pit ponies were in use there until 1968. Galleries extended far out to sea, over 1,000 feet below the surface. Nothing remains of the mine on the site, except for traces of rail track and the dock from which coal was exported by ship. On part of the site is a gas terminal, a complex tangle of pipework and towers burning surplus gas, which feeds Connah’s Quay power station. Further on, by the side of the road outside the village of Ffynnongroyw, the head-frame and winding wheel of one of the shafts have been re-erected as a memorial to the generations of miners who worked there.

The village itself, bypassed and quiet, is a wonderfully preserved example of a half-urban, half-rural mining settlement. Along its single street are houses in many styles, terraced and single. Some of the terraces are of three storeys, and of stone but with black-painted brick arches above the windows and doors. There’s a bewildering array of chapels, mostly closed or converted, and pubs, including ‘Tafarn y Gweithiwr’ and ‘Y Goron’, a tall building standing in sole splendor. Walker’s Ales are advertised in one of its elaborate Art Deco window. Y Goron and others are closed. Thirst as well as religion evaporated with the last of the miners. Water survives: a sign points the way to the eponymous well.

The village itself, bypassed and quiet, is a wonderfully preserved example of a half-urban, half-rural mining settlement. Along its single street are houses in many styles, terraced and single. Some of the terraces are of three storeys, and of stone but with black-painted brick arches above the windows and doors. There’s a bewildering array of chapels, mostly closed or converted, and pubs, including ‘Tafarn y Gweithiwr’ and ‘Y Goron’, a tall building standing in sole splendor. Walker’s Ales are advertised in one of its elaborate Art Deco window. Y Goron and others are closed. Thirst as well as religion evaporated with the last of the miners. Water survives: a sign points the way to the eponymous well.

On a busy road we pass the closed Lletty Hotel, with its picture of the ‘Honest Man’. The next place, Mostyn, has industrial roots like Fflynnongroyw, but here industry still lives. Exports leave the docks, including Airbus aircraft wings that travel from Broughton to Toulouse. There’s a chemical works, and a large shed is the centre for operating and maintaining the wind turbines off the coast. It would be even better if the turbines were built here. But Britain characteristically gave up on its nascent wind turbine industry many years ago, leaving the field clear to the Danes and others. The path runs along a busy road at this point, past a decommissioned but handsome classical railway station, before we cross the railway line and return to the coast.

On a busy road we pass the closed Lletty Hotel, with its picture of the ‘Honest Man’. The next place, Mostyn, has industrial roots like Fflynnongroyw, but here industry still lives. Exports leave the docks, including Airbus aircraft wings that travel from Broughton to Toulouse. There’s a chemical works, and a large shed is the centre for operating and maintaining the wind turbines off the coast. It would be even better if the turbines were built here. But Britain characteristically gave up on its nascent wind turbine industry many years ago, leaving the field clear to the Danes and others. The path runs along a busy road at this point, past a decommissioned but handsome classical railway station, before we cross the railway line and return to the coast.

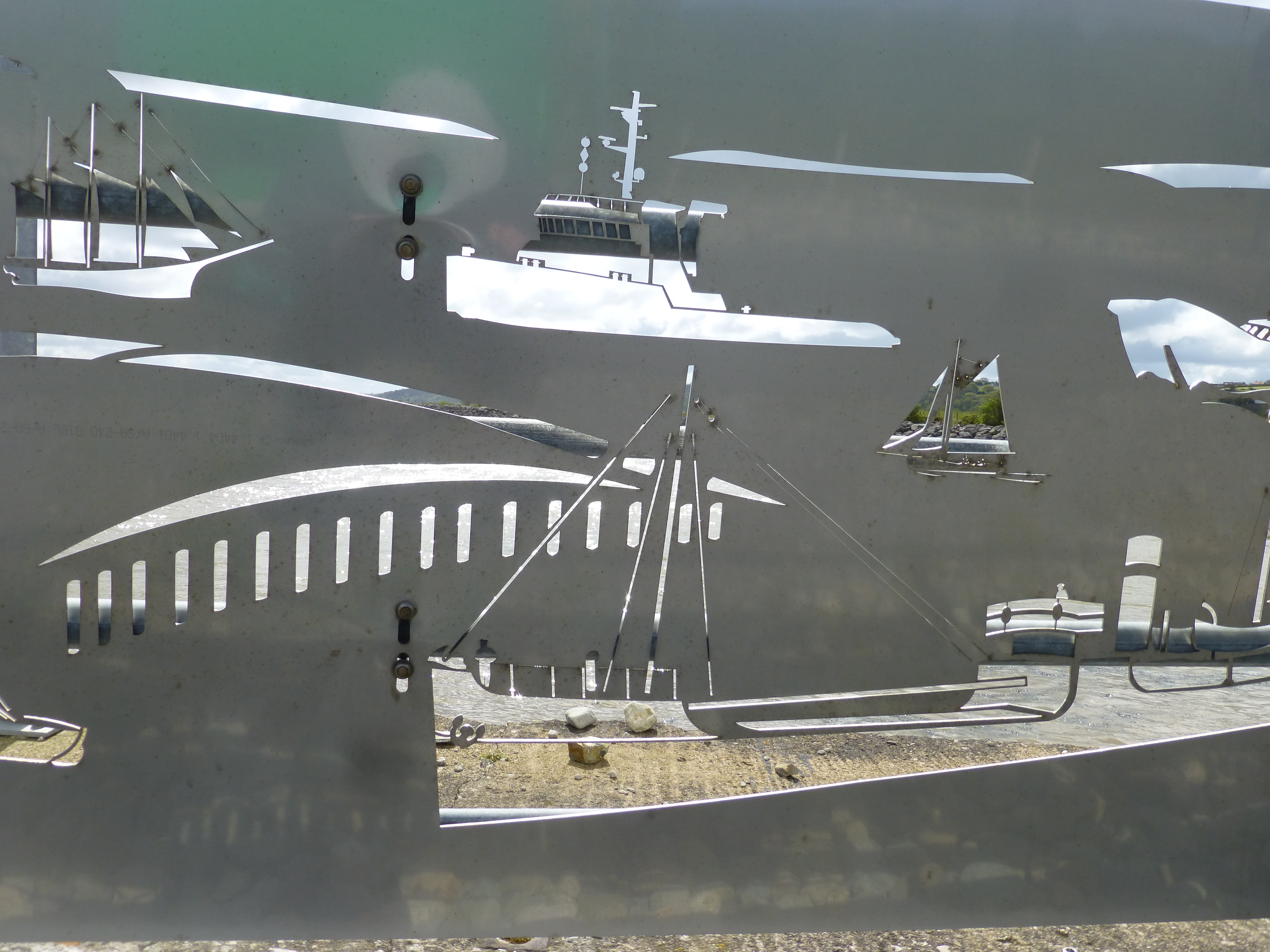

We stop for a picnic by the sea, where the Flintshire silhouette artist has again been at work, but the cold wind is still biting from the north-west, and we move on quickly along the path, to meet a strange sight. The Duke of Lancaster, a large hulk of an ex-ferry, is apparently sitting in the middle of a field. Officially it’s a wreck, wedged into a creek since 1979. It’s been used for various purposes over the years – for a time it was known as the ‘Fun Ship’ – and now there’s another attempt under way. The peeling and graffiti’d hull is being painted, all-black. Perhaps it’s to be a ghost ship or a vampire ship.

We stop for a picnic by the sea, where the Flintshire silhouette artist has again been at work, but the cold wind is still biting from the north-west, and we move on quickly along the path, to meet a strange sight. The Duke of Lancaster, a large hulk of an ex-ferry, is apparently sitting in the middle of a field. Officially it’s a wreck, wedged into a creek since 1979. It’s been used for various purposes over the years – for a time it was known as the ‘Fun Ship’ – and now there’s another attempt under way. The peeling and graffiti’d hull is being painted, all-black. Perhaps it’s to be a ghost ship or a vampire ship.

The estuary’s now beginning to narrow and we can see towns on the western side of Wirral. The stance of buoys shows that the tide’s turning swiftly. Sandbanks appear in parallel curved islands, and the water rushes seawards down channels near the shore. None of the coast’s famous oystercatchers are around, but curlews lift off in alarmed flocks from the mud. Now we’re walking through fields, sheltered by a rough rock seawall. Men in yellow jackets are walking and driving vans through the same fields. One of them explains that vandals with air rifles have been taking pot shots at the glass roundels on the telegraph poles. They’ve had to take the system down in order to find and repair the damage.

We reach Greenfield dock, where copper from Parys Mountain was once landed, to be made into objects exported to west Africa and exchanged for slaves to be worked on the West Indian sugar plantations. Copper nails and sheets were also made in the Greenfield valley to sheathe the hulls of slave ships sailing in tropical waters. At this point H, troubled by sore feet, leaves us to seek a cure in the magical Catholic waters of St Winefride’s Well at Holywell before she returns to Abergele by bus. C and I eat our sandwiches, watching dog-walkers as they scoop their pets’s shit into bags and throw them into the red boxes that are provided every few yards. (Every other person we meet on the north Wales coast seems to own at least one dog.) The path to Flint changes character regularly. Sometimes it skirts marsh, at other times it follows a high berm, then passes an old colliery amid blooming gorse, and ends in a birch wood. We pass Flint docks, now quiet but once busy with industry. A chemical magnate, drummed out of Liverpool for polluting the environment, set up in Flint and continued his polluting. Then suddenly we come upon the ruins of the castle, the beginning of Edward I’s iron ring of oppression. We ask directions to the railway station, a well-preserved building designed by Francis Thompson. A ‘mechanised foot’ statue with the punning title Footplate, sits by the platform. Then we fly along the track back to Abergele, in unaccustomed luxury and speed.

We reach Greenfield dock, where copper from Parys Mountain was once landed, to be made into objects exported to west Africa and exchanged for slaves to be worked on the West Indian sugar plantations. Copper nails and sheets were also made in the Greenfield valley to sheathe the hulls of slave ships sailing in tropical waters. At this point H, troubled by sore feet, leaves us to seek a cure in the magical Catholic waters of St Winefride’s Well at Holywell before she returns to Abergele by bus. C and I eat our sandwiches, watching dog-walkers as they scoop their pets’s shit into bags and throw them into the red boxes that are provided every few yards. (Every other person we meet on the north Wales coast seems to own at least one dog.) The path to Flint changes character regularly. Sometimes it skirts marsh, at other times it follows a high berm, then passes an old colliery amid blooming gorse, and ends in a birch wood. We pass Flint docks, now quiet but once busy with industry. A chemical magnate, drummed out of Liverpool for polluting the environment, set up in Flint and continued his polluting. Then suddenly we come upon the ruins of the castle, the beginning of Edward I’s iron ring of oppression. We ask directions to the railway station, a well-preserved building designed by Francis Thompson. A ‘mechanised foot’ statue with the punning title Footplate, sits by the platform. Then we fly along the track back to Abergele, in unaccustomed luxury and speed.

Leave a Reply