In sunny Flint C and I make for a recommended café in Church Street, Yr Hen Lys. It deserves the praise. The coffee is good and the bara brith even better. Back over the railway line, we make for the castle, only glimpsed the day before. A silhouette sculpture – Flintshire has dozens of them, for some reason – turns out to be not Edward I, hammer of the Welsh, who built the castle, but a visitor, Richard II, and his faithless dog Mathe. The castle and its grounds are neat, in Cadw’s normal landscape-as-nail-bar manner, and offer long views down the coast.

In sunny Flint C and I make for a recommended café in Church Street, Yr Hen Lys. It deserves the praise. The coffee is good and the bara brith even better. Back over the railway line, we make for the castle, only glimpsed the day before. A silhouette sculpture – Flintshire has dozens of them, for some reason – turns out to be not Edward I, hammer of the Welsh, who built the castle, but a visitor, Richard II, and his faithless dog Mathe. The castle and its grounds are neat, in Cadw’s normal landscape-as-nail-bar manner, and offer long views down the coast.

The path east skirts Flint Marsh. On it we spot geese, ducks, curlews and other birds. An information board – Flintshire County Council deserves a prize for supplying by far the best Welsh Coast Path panels – quotes a hapless poem written by Charles Kingsley, author of The water babies, about this coast, ‘The sands of the Dee’. The Flint sands claimed the lives of many, including a woman he calls Mary:

The path east skirts Flint Marsh. On it we spot geese, ducks, curlews and other birds. An information board – Flintshire County Council deserves a prize for supplying by far the best Welsh Coast Path panels – quotes a hapless poem written by Charles Kingsley, author of The water babies, about this coast, ‘The sands of the Dee’. The Flint sands claimed the lives of many, including a woman he calls Mary:

And o’er and o’er the sand,

And round and round the sand,

As far as eye could see

The rolling mist came down and hid the land –

And never home came she.

C wonders whether what Sigmund Freud would have made of Kingsley’s morbid obsession with babies, water and drowning.

Across the marsh in the distance we can see a mighty assemblage of metal: the chimneys of Connah’s Quay power station, the Flintshire Bridge across the Dee and the best pylon collection since Newport. Before then the path takes us along a main road, past the big tissue paper-making plant at Oakenholt and the reassuringly named Dependable Concrete. Then suddenly we’re in the shadow of the gas-fired power station. Four plain steel towers stand in a row, oblong with circular protuberances, like a set of toddlers’ wooden pegs, and beside them a line of shallow concrete bowls. The forest of pylons leading from the station masks the elegant radiating cables of the Flintshire Bridge, hanging from the upturned ‘Y’ of its concrete support.

Across the marsh in the distance we can see a mighty assemblage of metal: the chimneys of Connah’s Quay power station, the Flintshire Bridge across the Dee and the best pylon collection since Newport. Before then the path takes us along a main road, past the big tissue paper-making plant at Oakenholt and the reassuringly named Dependable Concrete. Then suddenly we’re in the shadow of the gas-fired power station. Four plain steel towers stand in a row, oblong with circular protuberances, like a set of toddlers’ wooden pegs, and beside them a line of shallow concrete bowls. The forest of pylons leading from the station masks the elegant radiating cables of the Flintshire Bridge, hanging from the upturned ‘Y’ of its concrete support.

Next there’s a long road-walk into the town of Connah’s Quay. We miss the unmarked Path as it makes a sudden turn down Rock Road and have to retrace our steps. In the narrow lane that follows a woman is struggling to control two vicious pit-bull terriers. They meet a third belonging to a rough looking man and two other people squatting by the side of the lane. A fight breaks out in front of us between the snarling, straining beasts. The man swears loudly and aims a violent blow to the back of his dog. The woman with him tells him to control his language in the presence of respectable people (us, it seems). Finally, the first woman succeeds, with some difficulty, in hauling her two dogs away down the lane, and we escape the scene as best we can. (A few days later a woman was sexually assaulted near this spot: it did not feel a safe place.)

Next there’s a long road-walk into the town of Connah’s Quay. We miss the unmarked Path as it makes a sudden turn down Rock Road and have to retrace our steps. In the narrow lane that follows a woman is struggling to control two vicious pit-bull terriers. They meet a third belonging to a rough looking man and two other people squatting by the side of the lane. A fight breaks out in front of us between the snarling, straining beasts. The man swears loudly and aims a violent blow to the back of his dog. The woman with him tells him to control his language in the presence of respectable people (us, it seems). Finally, the first woman succeeds, with some difficulty, in hauling her two dogs away down the lane, and we escape the scene as best we can. (A few days later a woman was sexually assaulted near this spot: it did not feel a safe place.)

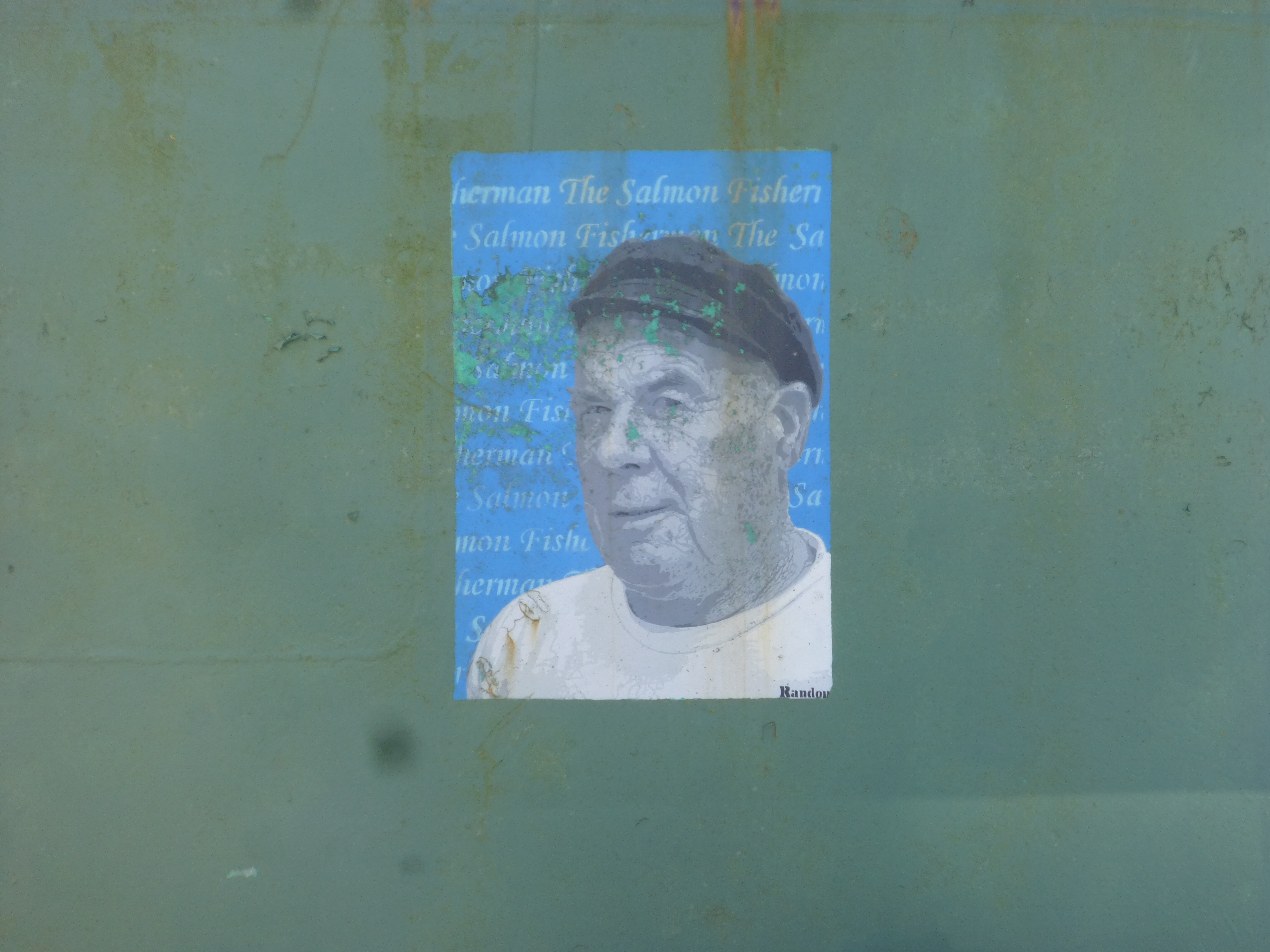

At last we’re down by the water. Almost nothing is left of what was once a busy port of Connah’s Quay, the successor to Chester after silting made the Dee unnavigable. Instead there’s a small suburb of workshops, tyre shops, a caravan café (Yvonne’s, with a picture of a salmon fisherman by Random, Flintshire’s answer to Banksy), and a pub, The Old Quay House, dating to 1777. This is where, earlier in the eighteenth century, the New Cut was built and the Dee canalised in a vain attempt to revive Chester as a major port. It proved too late – Liverpool had already taken the lead. Across the river are the blue sheds of the Corus steel works of Shotton (future uncertain). We shelter from the wind in the lee of a railway bridge across the river, and stop for a picnic. Across the water sits the castellated brick facade of the original Summers steelworks offices, built in 1907 by the sons of the clog-maker John Summers, who had captured most of the British market in galvanised steel. The building, now disused and dilapidated, looks like a parody of the gentleman’s country mansion, a deliberate provocation by the new industrial barons.

At last we’re down by the water. Almost nothing is left of what was once a busy port of Connah’s Quay, the successor to Chester after silting made the Dee unnavigable. Instead there’s a small suburb of workshops, tyre shops, a caravan café (Yvonne’s, with a picture of a salmon fisherman by Random, Flintshire’s answer to Banksy), and a pub, The Old Quay House, dating to 1777. This is where, earlier in the eighteenth century, the New Cut was built and the Dee canalised in a vain attempt to revive Chester as a major port. It proved too late – Liverpool had already taken the lead. Across the river are the blue sheds of the Corus steel works of Shotton (future uncertain). We shelter from the wind in the lee of a railway bridge across the river, and stop for a picnic. Across the water sits the castellated brick facade of the original Summers steelworks offices, built in 1907 by the sons of the clog-maker John Summers, who had captured most of the British market in galvanised steel. The building, now disused and dilapidated, looks like a parody of the gentleman’s country mansion, a deliberate provocation by the new industrial barons.

At Queensferry we cross the river on a handsome old bascule Blue Bridge. Now the walk becomes a long slog. A narrow strip of straight, level tarmac stretches, almost as far as the eye can see, along the river towards the border. It’s deserted except for a few lycra’d cyclists. They sneak up on us from behind, silently and at great pace thanks to the stiff north-west wind. Lacking bells, they shout at us imperiously to jump out of their way, so that they can avoid braking and losing momentum. The river’s grey and dead-looking. There’s no water transport and no fishermen. The flat land, with its enormous ploughed fields and wind-breaking trees, reminds us both of Lincolnshire. From a firing range in a group of trees to the left come gunshots. They sound methodical and serious. We start to wonder if the marksmen are preparing for the coming civil war against EU ‘remoaners’. Later a great shed appears on the other side of the river, where the wings of the Airbus are made at Broughton. At a wharf opposite the wings, each more than 36 metres long, are loaded on barges and floated downstream to Mostyn. Here they’re transferred to a special ship (we spotted one earlier in the week), taken across the sea and ferried up the river Garonne by barge to be attached to the fuselages in Toulouse. What Brexit means for this European collaboration is anyone’s guess.

At Queensferry we cross the river on a handsome old bascule Blue Bridge. Now the walk becomes a long slog. A narrow strip of straight, level tarmac stretches, almost as far as the eye can see, along the river towards the border. It’s deserted except for a few lycra’d cyclists. They sneak up on us from behind, silently and at great pace thanks to the stiff north-west wind. Lacking bells, they shout at us imperiously to jump out of their way, so that they can avoid braking and losing momentum. The river’s grey and dead-looking. There’s no water transport and no fishermen. The flat land, with its enormous ploughed fields and wind-breaking trees, reminds us both of Lincolnshire. From a firing range in a group of trees to the left come gunshots. They sound methodical and serious. We start to wonder if the marksmen are preparing for the coming civil war against EU ‘remoaners’. Later a great shed appears on the other side of the river, where the wings of the Airbus are made at Broughton. At a wharf opposite the wings, each more than 36 metres long, are loaded on barges and floated downstream to Mostyn. Here they’re transferred to a special ship (we spotted one earlier in the week), taken across the sea and ferried up the river Garonne by barge to be attached to the fuselages in Toulouse. What Brexit means for this European collaboration is anyone’s guess.

Our feet are feeling the punishment of the tarmac by the time we round a welcome corner in the river and reach the (seemingly arbitrary) border between Wales and England and the terminus of the Wales Coast Path. We’re not much more than a mile from Chester. As if to greet us, a group of swifts, the first we’ve seen this year, duck and dive around our heads. The border’s marked by two rough pillars of Halkyn stone, one on either side of the track. The conch symbol of the Wales Coast Path is carved on a broken stone inlaid at our feet. It’s a vaguely disappointing climax. We take some desultory photos of ourselves and trudge on into the city. Slowly the Dee becomes less like a canal and more like a river. A well-designed route guides us from the outskirts to the railway station along the Chester canal. At last we can stop and refresh ourselves – though it’s depressing to find that the railway station, a big graceless brick building, gives more prominence to a betting shop than to the café. C notices that the Arriva train back to Abergele & Pensarn looks very different from the sleek modern type we’ve used up to now. It’s old, noisy, dirty and uncomfortable, and it reminds him of the trains Arriva reserves for the south Wales Valleys lines. I look up and see an advert for the Parc and Dare Theatre in Treorchy. This is a Valleys train!

Our feet are feeling the punishment of the tarmac by the time we round a welcome corner in the river and reach the (seemingly arbitrary) border between Wales and England and the terminus of the Wales Coast Path. We’re not much more than a mile from Chester. As if to greet us, a group of swifts, the first we’ve seen this year, duck and dive around our heads. The border’s marked by two rough pillars of Halkyn stone, one on either side of the track. The conch symbol of the Wales Coast Path is carved on a broken stone inlaid at our feet. It’s a vaguely disappointing climax. We take some desultory photos of ourselves and trudge on into the city. Slowly the Dee becomes less like a canal and more like a river. A well-designed route guides us from the outskirts to the railway station along the Chester canal. At last we can stop and refresh ourselves – though it’s depressing to find that the railway station, a big graceless brick building, gives more prominence to a betting shop than to the café. C notices that the Arriva train back to Abergele & Pensarn looks very different from the sleek modern type we’ve used up to now. It’s old, noisy, dirty and uncomfortable, and it reminds him of the trains Arriva reserves for the south Wales Valleys lines. I look up and see an advert for the Parc and Dare Theatre in Treorchy. This is a Valleys train!

At Pensarn we can’t face the half mile walk home, and wait in the sun for the no.12 bus. Too tired to climb to the top deck, we sit in the seats reserved for old and disabled people. We dream briefly of the tea and hot baths awaiting us. Later, M, our first guestwalker, arrives from Wakefield, and we drive to the Black Lion at Llanfair Talhaiarn for a meal. For some reason the pub is under siege from several large vans, at least one from Ireland, claiming to be dog ambulances. It doesn’t make sense – but it’s been a long day.

Leave a Reply