In summer 1972 I made two happy discoveries within the Roman fortress that had occupied the centre of Exeter. One of them was human. That encounter changed my life for good. The other was inanimate. Its impact on me wasn’t as great, but it did earn a small place in the history of research on Roman Britain.

1972 was my second season of digging in the Roman fortress. Those were the days when important digs could employ over a hundred volunteers, and people came from all over the world to help. We lived in what were really communes, scattered in various houses in the city. There were two excavation sites, St Mary Major near the Cathedral, and the Guildhall, where I worked, which was near the centre of the fortress. At that time it was a car park, and later became a shopping centre (maybe, post-Covid, it’s on its way to becoming something else). John Collis and Michael Griffiths were in the charge of the excavations.

In the Trichay Street area I was given a pit to dig out, slowly, using my old worn trowel. The hole had been re-used as a cesspit in medieval times, but its lower, waterlogged strata preserved a wealth of Roman rubbish, including pottery, glass and wood, which seldom survives from that period. By now, after a couple of weeks of excavation, the hole was becoming deep. In fact, I’d disappeared from view. (Today the walls would probably have been reinforced to avoid the danger of being buried alive.) By now I’d become quite possessive about ‘my pit’. There was something satisfying about working mainly alone, in T-shirt and blue sunhat, in my personal underground Roman kingdom.

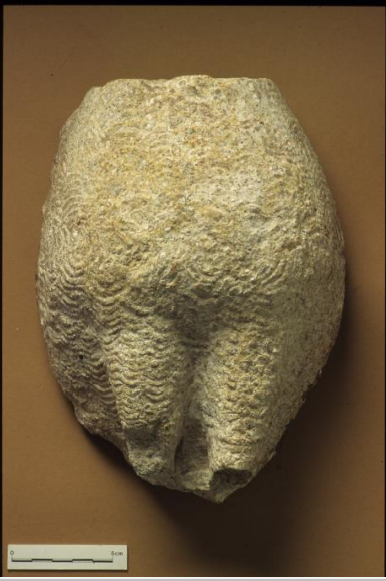

One day I came across a large stone object. It had been carefully shaped – in fact, sculpted. Once it was cleaned it wasn’t difficult to see that it was an image of part of a bird, around 20cm in length. Only its torso, because the head, wings and lower legs were all missing. The surface had been chiselled into wavy curves to suggest feathers. Worked stopped on the site, and everyone gathered around to look at the stone. Then it was sent to Oxford, to Jocelyn Toynbee, the leading authority on Roman art in Britain at the time. She later wrote a piece for the official excavation report.

The bird, it turned out, was an eagle, and the sculpture was made from Purbeck marble. Because the pottery fragments that surrounded the stone could be dated to the second half of the first century AD, the piece was one of the earliest pieces of Roman sculpture yet found in Britain (and the first made from Purbeck marble). The Exeter fortress was established in around AD 55, by the future emperor Vespasian, to house his Second Legion, charged with ‘pacifying’ the south west of England, and the eagle may have come from a sculptural group set up in the principia, or headquarters building, soon after. The back of the piece was flat, so it could have been attached to a wall or formed part of a relief sculpture group.

There are other examples of the species from Roman Britain. In 1866 a bronze figurine of an eagle was found in the forum of the town of Silchester in Hampshire. Though its wings are missing, it’s a detailed, realistic and finely-crafted work. It was probably part of a larger sculptural group, possibly featuring an image of the emperor. (This eagle inspired Rosemary Sutcliff when she came to write her novels The eagle of the Ninth and The silver branch.) In 2013 a remarkably complete Cotswold limestone sculpture came to light in a Roman cemetery in Minories in the City of London: an eagle with a snake in its beak. The Silchester and London eagles give a vivid impression of the message they were intended to convey: one of irresistible force and power. The eagle was the symbol of the most powerful of the gods, Jupiter, and in Roman sculpture is often found sitting at his feet. It was also associated with the emperor, Jupiter’s earthly equivalent, and had a link with immortality and apotheosis. And, of course, an eagle, perched on a thunderbolt, topped the standard that led a legion into battle.

There are three other stone fragments of eagles from Roman Britain, but the Exeter eagle is unique in that its head was deliberately removed – possibly because it belonged to a group including the emperor Nero, whose images were often destroyed after his death in AD 68. (This de-facement, or damnatio memoriae, was the Roman forerunner of Joseph Stalin’s photographic erasure of executed enemies.)

In my memory, that summer still carries a special aura. After the dig I went back to university and studied classical archaeology, but never became the archaeologist I seemed to be preparing to be. I’ve been back to Exeter a few times since. On the last occasion I went looking for the stone eagle in the Royal Albert Memorial Museum. It wasn’t on show. Maybe it’s resting in some basement store, waiting to be discovered again.

Leave a Reply